Single to Ego City

Some, all or none of the below may or may not be fact or fiction. Or both. Phil Latham takes no responsibility for anyone believing what he says to be true or helpful or entertaining. Ever. No pint glasses were shattered during the creation of this blog.

******

I have interviewed myself to make the blog different (partly) and because I am not getting paid for this (mainly). Apologies for the inelegant formatting (blame Bill Gates) and if I have used an incorrect interview format (blame the interviewer).

Interviewer: Who are you?

Me: As DeLillo might write, ‘I am a fake, a fraud, an impostor, a charlatan.’ Who I am is normally a question I reserve for special occasions, when I’ve consumed too much alcohol or when I’m marooned in a queue and trying with all my powers not to visualise a trolley, a chainsaw and an infinite tank of petrol.

Interviewer: So you’re not a writer?

Me: Yes. And no. Maybe. Perhaps. I do write, a novel mainly, but also the occasional short story when I can be occasionally energised. But I’m not a writer. People like Douglas Adams and Nick Hornby studied English at university. I didn’t.

Interviewer: What did you study?

Me: Girls through telescopes. And my navel. For my navel gazing I received a First; for studying girls I received pokes in my other eye. My ‘study’ of English expired when I was sixteen so I know very little. I have never studied Dickens or read poetry by Wordsworth. Shakespeare was a barber, right?

Interviewer: You think you’re a fake because you didn’t study English as a degree?

Me: It’s not just that. All the time writers and poets say ‘I have always written’ and I know that’s not me. I’m not and have never been someone who has always written, always wanted to write, as if writing is my oxygen. Writing is my Shreddies.

Interviewer: If you don’t write, what are we doing here? I could be in the pub.

Me: I do write, but I’m not a writer. I’m not qualified. I don’t live to write. I’m just a guy hunched over a keyboard making it up. Those at the back of the queue may be pining for an academic definition for ‘writer’, but my stock response as unoriginal and inexact as a mother-in-law joke is ‘someone who is published’. Perhaps a writer is someone who is published and who makes the majority of their income from writing. Are you a writer if you have not had your short stories or novel or poetry published? Maybe. Are you a writer if you don’t make the majority of your income from writing? No, I don’t think so. If your main job is selling used cars and you just happen to write science-fiction (because you’re into lying 24/7), then your occupation is metal pusher, not writer. I have a full-time job and write part-time. I am a fake.

Interviewer: Have you had anything published?

Me: One piece of flash fiction and one short story, both online. But nothing major. Nothing that snaps knicker elastic at magnification times ten.

Interviewer: How did it feel to see your work published online?

Me: For an entire day my face became an electrified banana.

Interviewer: If you haven’t studied English since school, how have you developed your writing ability?

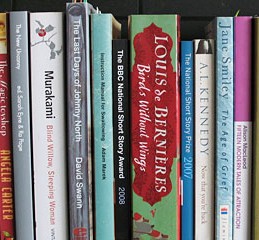

Me: Some would say I haven’t. But I read a variety of fiction and have trawled a few ‘How to’ books.

Interviewer: If you write yet insist you’re not a writer, what are you writing for? Why bother?

Me: I started writing by accident.

Interviewer: You strolled under a ladder, a plant pot fell on your head and you awoke with pencil and paper in your hand?

Me: I started writing because of boredom. Can you believe that?

Interviewer: No, I can’t, and if you don’t start making some intelligent remarks I am going to the pub to make up the rest of this interview, like a proper journalist.

Me: I often work away and when summer weeks stretched into winter months, boredom became a sumo wrestler squatting over me after he’d dislocated a chicken madras. I watched TV, devoured my DVD collection. I read. Biography, fiction. I’ve never been interested in anything miserable, because if I want to witness human suffering I can stare out of the window or watch The X Factor. So I read humorous novels by people like Tom Sharpe, Douglas Adams, Nick Hornby and Ben Elton. One day I read another author and afterwards I just thought I could do better.

Interviewer: Really?

Me: Yes, really.

Interviewer: You didn’t think you were being arrogant? Ambitious?

Me: No, because when that thought skateboarded into my mind I didn’t plan on doing anything about it. I didn’t plan on wanting to write a novel, badly.

Interviewer: But now you have?

Me: Yes, now the novel is written badly. I was bored one afternoon at work and rather than typing yet another report about nothing in particular, the blank screen in Word goaded me into imagining a scenario to make me laugh. So I visualised a couple on a first date, in a bus shelter, in the rain. It’s midnight, the end of the date, and while he’s waiting for the bus home she decides to progress the date physically. The situation made me smile, and was a worthy distraction from work, so I developed the idea. It’s not explicit erotica or anything, although events do evolve. The rain is so dense it curtains the darkness even more and, just at the climax, just as the man thinks this is the feeling in the world and nothing can spoil it, a flashgun goes off.

Interviewer: Someone has photographed them in the bus shelter?

Me: Exactly. They’re semi-naked enjoying themselves and a journalist photographs them, which I thought was comical. It was just me being bored, my brain rebelling at the tediousness of the office.

Interviewer: What happened to the scene?

Me: It ends one chapter in my novel. Once I’d written it I thought about it more, so I read more. Writing fuelled the reading; reading fuelled the writing. Of course I’d created one scene, not a short story or novel, so around it I had to scaffold the remainder of the story. Characters, plot, setting. Usual convicts. It hasn’t been an efficient method of writing, but then what is? And because I’d never studied English I was blind, assembling endless word parcels with no idea that most of them would never be posted.

Interviewer: So why am I here?

Me: Ask your mother and father. What changed is I found thinking of situations, characters and jokes more enjoyable than decaying in an office, which is ironic given that the office is the great joke.

Interviewer: But because you write part-time, you still do the office work?

Me: Yes, I still do that head in a blender process. I wrote thirty thousand words and grappled with alien concepts and techniques such as the subjective narrator, foreshadowing and building tension. Eventually I reached a point where I needed feedback. I knew what I’d written wasn’t publishable because it didn’t match the quality of fiction I was reading. Yet I didn’t know how to make it publishable.

Interviewer: Didn’t the ‘How to’ books help?

Me: To a point, but they aren’t the same as someone reading your work and saying what they think. Later I met my old English teacher at a school reunion and when I told him I was messing around with a novel he encouraged me. Although what I’d written was first-draft-drivel, he offered me useful advice and, after re-drafting, those thirty thousand words became fifteen. That’s fifteen thousand, not fifteen. Despite the word decapitation I had a plot and characters and wanted more feedback as a method to improve. So I applied for a MA in Creative Writing. I’m halfway through and thanks to the workshops I’ve had great responses.

Interviewer: Good and bad?

Me: Good and bad. The problem with writing is that I do it in isolation. Laptop, tap, tap, tap, sleep. Usual story. The MA has been valuable for feedback but also because the tutors treat me as a writer – when clearly I’m just a fake – and encourage all students no matter whether they write short stories or poetry or anything to submit their efforts to journals and competitions. Think like a writer, act like a writer. So my aim is to finish my novel and send it to an agent. The odds are against publication, but I’ve got to try.

Interviewer: Thank you. You don’t mind sharing this information with the world?

Me: I don’t mind. It’s not as if you know any of my personal details or anything. Name, address, inside leg.

Interviewer: Indeed. For this interview it just remains me to thank Phil Latham of Melbourne Road, Chester, thirty-three inches.

Very funny article. I totally relate. It’s taken me a long time to believe myself to be one. Yes – the ultimate is to get paid and published – but that’s not why I do it. Despite enormous road blocks I’ve found myself writing and writing but my greatest enemy is fear especially since the road I took to get to this point is not the established one.

This little scenario has played through my mind.

“Hi I’m Amanda,” I say.

“I know,” says My Alter Ego.

“I’m a writer,” I say.

“Who says?” reples My Alter Ego.

“I do.”

“And?”

“Tell you something else,” I say.

“What?”

“I’m also incredibly beautiful.”

“Yeah right.”

Also this one…

“Isn’t that Amanda,?” observes My Reader.

“Maybe,” says My Alter Ego.

“Isn’t she a writer?” My Reader asks.

“Possibly.”

“Doesn’t she write amazing stuff.?”

“She likes to think so on occasions, I believe.”

“And she’s totally beautiful, isn’t she?”

“Ahahaha. Matter of opinion.”

The discussion sparked by Phil’s original post will be a familiar one to all of us who write: can a person who writes, but isn’t published (regularly) and paid for his work, legitimately call himself a writer?

If the answer is ‘no’, then surely practitioners of other artistic pursuits are bound by a similar rule. Following this, Vincent van Gogh, who painted nearly 900 paintings in the last decade of his life, but sold only one, would not have been entitled to call himself an artist. And yet he went on to become one of the most widely-recognised, influential and highly-regarded painters of the late 19th century. Did he only earn the right to be called a painter once his paintings were deemed to have monetary value? I have little doubt that, successful or not during his lifetime, he would have considered himself and been considered by others to be a painter.

Pauline makes the point that someone who plays the piano is, to one degree or another, permitted to call himself a pianist regardless of whether or not he makes his living this way. If we apply this argument to a person who has plumbing qualifications but does not earn their living from this trade, can this person be called a plumber? One could conceivably be called an amateur plumber – one who plumbs without financial gain – but it’s unlikely that a person would apply this label to himself or be seen by others in this way. Apart from DIY enthusiasts, people generally practice a trade for financial reward. Any personal satisfaction they may gain is secondary. I daresay that apart from people in the creative arts field, very few would be prepared to practice their craft indefinitely without the certainty of one day receiving financial reward.

Most of us who pursue an artistic career, of one sort or another, do so not simply for the potential cash rewards but because we cannot not pursue our art. Artists are compelled by a desire for self-expression and it is this compulsion, I would argue, that makes us artists – not the level of recognition or payment we receive. The tendency to commercialise artistic pursuits implies that the art produced only has value if there is a monetary figure attached to it. This has to be an incorrect assumption. Surely the value of a piece of art is in the art itself. It may be substantial or minimal at different points in time, as seen in the example of van Gogh, but ultimately is detached from a price tag.

My guess is that when he is not writing, Phil is thinking about writing, and if he’s not thinking about writing, then his writing is percolating away in his subconscious. Otherwise, why would he be pursuing an MA in Creative Writing and why would he be a regular blogger on a writing website? I have every belief that Phil can legitimately call himself a writer. Now if only I could say as much for myself…

Loree has suggested that “very few would be prepared to practice their craft indefinitely without the certainty of one day receiving financial reward. ” I would cite as counter-examples of this the many people who work as parents, carers, home-makers or in voluntary roles for charities and other organisations, often working hours that would be described as a “full-time” occupation if it were a paid career. Many of these will never receive a penny for their labour and they have chosen to give it freely. Many of the people who call themselves writers do the same. So it is not just those driven by the need for artistic expression who work for free.

I would be extremely interested to know how many people today are actually making a living solely from short-fiction writing, not supplementing it with income from other types of writing, from teaching, public speaking, critiquing, editing, judging competitions and other forms of related activities. If a writer gains more of their income from teaching on writing courses than from their publications then perhaps they should be describing themselves as a “teacher” rather than a “writer” and yet, ironically, they have probably only been engaged to lecture because they are perceived as a “writer” rather than as “a teacher who writes.”

When my first short stories were published in small press anthologies, about ten years ago, it was typical to receive a fee of around £50 per story. These days I count myself lucky if the publisher can spare a single free copy of the anthology by way of payment. Am I any less a writer now than I was then? I can only think of one occasion when I have been comissioned in advance to write a story for payment. Therefore, just as Van Gogh was not an artist, presumably neither I nor J.K. Rowling when writing her first Harry Potter book were writers whilst actually writing, but only became writers when we stopped writing and received a cheque for our work. It’s an interesting definition…but not one that I find I can easily subscribe to when most short story writing is done speculatively without the comfort of a three book deal to allow the non-writer to qualify as a “writer”.

Thank you for your thoughtful comments.

Although I write, however loose the definition, I still feel like a fraud.

How can I, a bloke off the street, have the temerity to call myself a writer when I write part-time (at best), some weeks producing two thousand words, some weeks nil?

Each and every day of my life shouldn’t I be up at 6am and writing solid slugs of prose until 6pm? And then spending the evenings re-reading my efforts until I feel sick with the knowledge of my internal repetitions, with the widsom of my inner voice nagging me to do better, to get a proper job, to think and write and ponder and deliver like Hemingway and Dickens and Roth and Amis?

Sometimes I do feel like a writer. Sometimes I do finish that scene and a rush bubbles up through my pores, as if I have written my first Proper Scene. A scene worthy of the tag of writer.

But most days that does not happen.

And, most days, I know I am writing material that (probably?) will (maybe?) never be published (perhaps?).

So most of the time that I spend writing, even if it amuses me, does so on a level that also annoys. It annoys because part of me thinks (knows?) that I am wasting my time.

What is the point of writing a novel if it will never be published?

What is the point of writing?

What is the point?

What?

I’m veering towards Phil’s definition of a writer, certainly a professional writer is someone who is paid for the work. I suppose an amateur who plays the piano could be called a pianist, but no one would compare him to Stephen Hough. The issue it seems to me is that whereas it takes around two decades of practice and lessons to come anywhere near considering oneself a professional pianist, nearly everyone can write…

Phil Latham’s question (to himself) about when those who write can justifiably call themselves writers made me smile. It was a wry smile of recognition.

When I confess to someone that I’m a writer, one of the most popular responses is “have you had anything published?” I very much doubt that if I’d said “I’m a pianist” the same emphasis would be placed on whether or not I had made any recordings or played any concerts lately. But whilst it is perfectly socially acceptable to play the piano for an audience of none, or perhaps to teach piano or work occasionally as an accompanist or performer, the same is not true of writing. The tag “published writer” seems to be the only one which confers any respect upon the declaration that one writes.

Luckily I can play the “published writer” (and “broadcast writer”) card if and when I need to. But I recognise that I know a number of extremely accomplished writers who have never (to my knowledge) had their work published in print. Of course, people still frequently make a distinction between “online” and print publication in terms of credibility.

I could start in on the whole issue of remuneration for writing short fiction and whether or not that conveys anything useful about its worth, but then we’d be into a whole new blog post rather than just a cheeky reply to Phil’s.

To be honest, I don’t think there is any litmus test you can apply to identify a “real” writer. It’s a self-identification, just as ethnicity is. So if you think you’re a writer, you can say that you are. A whole bunch of people, including me, may be sceptical about your assertion by virtue of our own value judgements…..but, frankly, we can’t touch you for it.