by Dora D’Agostino

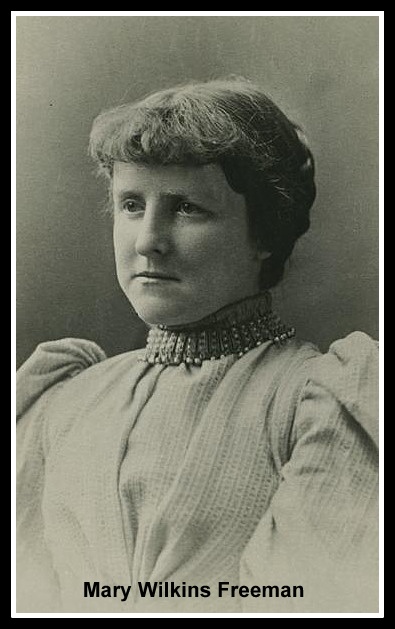

Who knew that Mary Freeman and I would have so much in common? Mary Ella Wilkins Freeman was born on October 31, 1852 in Randolph, Massachusetts, while I was born in a small Italian town; exactly 100 years later (give or take a few years). I was first introduced to her work during my undergraduate days but it wasn’t until much later, when I began searching for a writing voice I could call my own, that I was reintroduced to her work. Despite trying to write cosmopolitan stories that took place in my new, adopted country, I would invariably find myself returning to the days of my youth. By the time I made peace with this fact, I realized that I had forgotten many day-to-day details of small town life in Italy. So how could I write convincing stories if I couldn’t remember? I needed to find a mentor who could teach me how to make my stories real so that they resonated with the reader. And so the quest to find an author I could relate to began.

I looked for guidance from Anne Beattie, John Barth and John Cheever without success. Even J.D. Salinger, whose Holden Caufield and Franny and Zooey seemed likely inspiration for my own characters, didn’t make the grade. It wasn’t until I read Mary Freeman’s stories that I knew I’d found the one – my spiritual mentor.

From the very first story I read, in The Short Fiction of Sarah Orne Jewett and Mary Wilkins Freeman, I felt right at home in her company.

From the very first story I read, in The Short Fiction of Sarah Orne Jewett and Mary Wilkins Freeman, I felt right at home in her company.

In “A Mistaken Charity”, two sisters, Harriet and Charlotte are picking dandelions greens: ‘…and two old women one with a tin pan and old knife searching for dandelion greens among the short young grass… watching her.’

I couldn’t believe it! As I read, a flood of memories returned to me. I vividly remembered walking the green fields near my childhood home, looking for chicory, playing house and imitating the poor women of our town who, like Harriet and Charlotte, foraged the countryside for food.

Story after story reminded me of the strong women who populated the cobblestone streets of my town. I was amazed to realize that though a century separated us, our lives were very similar. But how could this be?

Growing up female in a small Italian town during the 1950s is not as idyllic as you might think. Italy at that time was a highly patriarchal and provincial society. The best way I can describe it is to compare it to living in a Jane Austen novel – 100 years after her novels were written!

Even at the age of ten, the age I was when my family left Italy for the United States, I knew I was leaving behind a society that would have ensnared me had I stayed. Mary Freeman’s characters, though, were never given an opportunity to break away. They remained bound by the traditions and customs of their time. Yet despite the enormous odds, they held on to their inner convictions. The fact that Mary Freeman gives them this power was, and is, what makes her work so revolutionary. She gives a voice to impoverished women who live and work in obscurity, and in doing so, she gives us all a glimpse of how our lives could be: how they might be worse than they are; how they might be better. At the same time, she highlights the way patriarchal rules and society’s conventions can inhibit a woman’s individuality. In a world where many women are still enslaved and subjugated by tradition, her stories continue to offer an important glimpse of liberation.

Two of Mary Freeman’s stories, “A New England Nun” and “Louisa”, pose the question of whether a woman should marry and risk losing her identity or remain single. In both stories, the heroine is named Louisa, and in both she decides not to marry. In “A New England Nun”, Louisa Ellis is all set to marry her long-time beau, Joe Daggett, until she overhears a conversation which changes her mind. The ending is a bittersweet one, yet it is not entirely unexpected. Freeman tells us in detail how Louisa feels her life has achieved a fine equilibrium, one that she would lose if she married Joe. Yet Louisa longs for love. Louisa Britton on the other hand doesn’t want to marry someone she doesn’t love for the security alone – even though she and her mother could, quite literally, die of starvation.

Both women have an integrity and an independence that is admirable. It’s sometimes hard to believe how they and the other women in this collection are able to persevere, despite the forces bearing down on them, and it’s a pleasure to see how each overcomes the obstacles they confront. Were we in their place, could we endure as well?

Perhaps this is the reason why I like Freeman’s stories so; there’s not one simpering woman to be found and her characters are so alive they really do seem about to jump off the page. We might not agree with the choices they make, but they succeed in forging their own destinies. In the story “One Good Time”, Narcissa is finally free to marry, after her invalid father dies, taking up her rightful place in society. But she risks it all for the chance to have one good time.

I love Mary Freeman’s strong and determined female characters and also her direct way of telling stories. A novice writer can learn a lot from studying her story structure and the simple, yet spot-on metaphors that make her work come to life.

Mary Freeman is called a ‘regional colorist’ and rightly so as you can see and feel the colors, sights and sounds of her New England town. Read this beautiful passage from “A New England Nun”:

It was late afternoon and the light was waning. There was a difference in the look of the tree shadows out in the yard. Somewhere in the distance cows were lowing and a little bell was tinkling; now and then a farm wagon tilted by, and the dust flew; some blue-shirted laborers with shovels over their shoulders plodded past; little swarms of flies were dancing up and down before the people’s faces in the soft air.

Freeman is also astute at capturing the psychology and nuances of her characters and her writing has been compared to that of Henry James and, because of her use of dialect, to Mark Twain. She was a very prolific writer, producing more than two dozen story collections and novels, and her work was widely celebrated. In 1926 she was awarded the William Dean Howells Medal for distinction in fiction and she was one of the first four women ever to be elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

You can feel the depth of feeling that Freeman has for her characters for she herself suffered much sorrow during her life. Her father lost a number of businesses when she was young and the family moved house frequently. To help keep a roof over their heads, her mother worked as a housemaid. Death was also a constant in her early life: a younger brother died when she was six, and a younger sister when she was twenty-four. Both her parents died a short time later. No wonder the women in her stories are strong and independent!

You can feel the depth of feeling that Freeman has for her characters for she herself suffered much sorrow during her life. Her father lost a number of businesses when she was young and the family moved house frequently. To help keep a roof over their heads, her mother worked as a housemaid. Death was also a constant in her early life: a younger brother died when she was six, and a younger sister when she was twenty-four. Both her parents died a short time later. No wonder the women in her stories are strong and independent!

It is little surprise that Freeman favors poor and downtrodden characters in her stories. Some stories, though, veer so far from reality that they can almost be read as fairy tales or as wish fulfillment. One such story is “One Good Time.”

Personally, I had difficulty believing in a character who, after living in poverty and want for so long, and inheriting quite a bit of money, would consider spending it all for one good time. I know for certain that the women I grew up with in Italy would never have done such a thing! According to Leah Blatt Glasser from Georgetown University, Freeman, herself, admitted that some of her stories were pretty far-fetched, citing an interview published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1917. Disparaging one of her own stories for its lack of realism, Freeman said:

In the first place all fiction ought to be true and “The Revolt of Mother” is not true. . . . There never was in New England a woman like Mother. If there had been she certainly would have lacked the nerve. She would also have lacked the imagination. New England women of that period coincided with their husbands in thinking that the sources of wealth should be better housed than the consumers.’

Like “One Good Time”, the story just doesn’t ring true. Yet we owe Mary Freeman a debt of gratitude for even though some of her stories are not realistic, they offer a glimpse of how life could be. Her stories raise women’s consciousness and pose the idea that women have the same yearnings, capabilities, and drive to succeed as men – a revolutionary notion at the time of writing, and equally revolutionary for many women today. According to a biographical sketch on the Randolph Historical Society webpage, Mary Wilkins Freeman ‘…is often considered an early feminist writer, placed in the same category as writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and Sarah Orne Jewett’ and while her work has sometimes been viewed as too provincial and focused on life in New England, ‘new scholars are finding that her characters are more universal and timeless.’

I, for one, heartily agree. Women still struggle with the challenges faced by Freeman’s heroines: having a career, starting a family, or needing to fight for a plum position at work. I love that the rallying cry for many of her characters challenging the status quo is ‘Why Not?’; their dogged determinism cuts through all obstacles. Could Freeman’s affinity for these women have stemmed from finding herself in some of these same circumstances when her own family fell on hard times? Most definitely, yes. What else could have given her such empathy for the poor and unfortunate?

But there is a dark side to this strong will and determination; it can also have heartbreaking consequences. Take my favorite Freeman story, “Old Mother Magoun”:

The hamlet of Barry’s Ford is situated in a sort of high valley among the mountains. Below it the hills lie in moveless curves like a petrified ocean; above it they rise in green-cresting waves which never break.

The forces of good and evil as represented by Mother Magoun and Nelson Barry, co-exist side-by-side in Barry’s Ford until the day the two adversaries battle it out over Lily, Mother Magoun’s fourteen-year-old granddaughter.

Freeman describes Old Mother Magoun as a force of nature, resolute in the pursuit of her beliefs. She is one feisty old woman, proud and strong, and she is afraid of no one – least of all Lily’s estranged father, Nelson Barry.

We are told that Nelson Barry is a ‘…fairly dangerous degenerate of a good old family’ and that he has ignored his daughter for years, only taking an interest in her when he realizes she has a value to him. Deep down, Mother Magoun knows she can’t stop time but she is like a ‘petrified ocean’ when it comes to Lily. She feels much, but her stubbornness prevents her from acknowledging the truth. The day she has dreaded – the day Lily’s father notices her beauty – has come and Mother Magoun summons all of her resources against him.

Freeman tells us that everyone in town is afraid of Mother Magoun and knows there will be hell to pay if they ever dare to cross her, everyone except Nelson Barry:

Old Woman Magoun said [my emphasis] that her daughter, Lily’s mother, had married at sixteen; there had been rumors, but no one had dared openly gainsay the old woman. She said that her daughter had married Nelson Barry, and he had deserted her.

Old Mother Magoun is determined to keep Lily ‘pure’ by keeping her a child as long as possible. When the girl, still clutching her rag doll, is sent to run an errand, she accidentally comes to the attention of Nelson Barry. Before long, he comes to reclaim Lily, not because he loves her, but in order to pay a gambling debt to Jim Willis, another good-for-nothing, from a family ‘… worse than the Barrys…’ Old Mother Magoun knows that despite her efforts, it’s only a matter of time until, by law, she will have to give the child up to her father. She also sees that Lily ‘did not shrink from [her father]. Hereditary instincts and nature itself were asserting themselves in the child’s innocent, receptive breast.’ It is here that a desperate fight between good and evil begins and we see that despite having been taught to be good and kind and honorable, and kept secluded from the evil of the world, Lily is willing to become part of it. Mother Magoun tries in vain to find a solution, but when she knows there’s nothing else she can do, she finds the ultimate way of keeping Lily pure. The ending of the story is heart-breaking.

In the introduction to The Short Fiction of Sarah Orne Jewett and Mary Wilkins Freeman, Barbara H. Salomon writes: ‘Feminists have found a surprising modernity in the roles dramatized by Jewett and Freeman.’ Although most of Freeman’s stories are more than a century old, they remain very relevant today. Her themes are universal in scope and the struggles faced by her characters are timeless. They are the same struggles faced daily by women throughout the world. But the joys she depicts, are eternal. And it’s that which, despite the many sorrows, gives all of us hope.

*

So glad you’ve been inspired! This is what I like about THRESHOLDS: it gives everyone a voice so we can sample the myriad of voices that exist in literature. I still haven’t read all of her stories but i’ve bookmarked her page so I can enjoy them whenever I can.

So glad you enjoyed her stories Amanda. I’ll have to dig out “The Mayor of Casterbridge” – it’s been ages since I read it. I’m sure I have a copy of it in my library. A character’s moral dilemma certainly keeps me reading though I now see that I don’t always put enough of it in my own short stories. Thanks for reminding me of this fact.

l would love to read her novel “Pembroke” and see how it compares to her short stories. When I re-read her collection for this essay though it felt like I was reading a novel, for the obvious reasons. I was astonished to find she wrote so many more which I look forward to reading for free — thanks to the Internet. As far as my novel, I’ll have to find my way back to it: I started out so full of passion but now I feel that I’ve lost steam.

Hi Dora,

What an interesting piece. Mary Freeman sounds a fascinating woman – I’ll look forward to discovering her work. I enjoyed the parallels you draw with women’s lives today – and the battlecry of ‘Why Not?’ That really is inspiring! It sounds like her stories still have plenty of relevance to contemporary lives. I think I’ll start with ‘One Good Time’ – I like the idea of ‘a glimpse of how life could be’. Thanks Dora!

Dora, I enjoyed reading ‘A New England Nun’ for all the little needlework details and especially for the image of Joe and Louisa sitting stiffly at the table like a couple of hard chairs. I also felt that she could easily have gone a different route with the character of Lily. The decency of not turning Lily into a floozie (although we have the possibility of an offstage kiss) is sort of how I imagine the New England morality of the time. Old Woman Magoun made me think of The Mayor of Casterbridge. Something to do with the gambling debt I suppose. Hardy’s characters are more complex, I think you’d agree and the Dorset countryside is more brooding, but I found the story gripping and also spacious, and again we have that dreadfully compelling moral dilemma. I’ve been trying to think of British women writers who lived at the same time. I can’t think of any. I suppose Virginia Woolf is almost contemporary. I think Mary Freeman was born after George Eliot.

Your novel, by the way, sounds absolutely fascinating.