photo by Ivo Bouwmans

by Vicki Heath

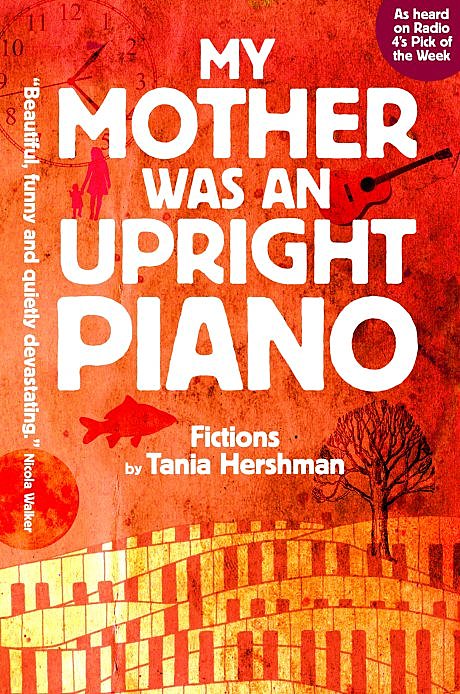

In her latest collection, My Mother Was An Upright Piano: Fictions, Tania Hershman has created fifty-six very short fictions, in which every word is perfectly placed as she explores the offbeat world we live in. Hershman spent thirteen years working as a science journalist, before concentrating on writing fiction. Perhaps it is the investigatory nature of science that leads to her scrutiny of the details of everyday life – from the observations of people and even trees, to her use of the senses and of colour. But whether it comes from science, or is a natural gift for observation, Hershman’s uncanny use of the minutiae works with such power that these stories are still hovering in my thoughts though I finished reading the collection days ago.

Many of the stories in My Mother Was An Upright Piano come with reflections on human nature, which Hershman reveals on the page in uninhibited forms. At the beginning of ‘Ankle Socks and Hair In Bunches’, the protagonist grudgingly welcomes her sister into her home. As the story unfolds we learn that the protagonist has recently lost her husband, William, and the sister has come to help her through her desperate mourning. The sister distracts the protagonist with walks and conversation. Yet expertly threaded through the story are subtle currents of grief: ‘We go out. Me, bundled up and sweating, you propelling me along. I’m paralysed by a row of ants. Or a child on a bike. You have to nudge me into motion.’ This numb sense of being is something we all experience and can relate to, making the use of second person narration unusually powerful here. When the sister eventually has to return to her own home, the protagonist panics, attacking her sister: ‘My nail catches on your cheek, there’s blood, but you don’t defend yourself. You’re crying, then I am too and we stand, locked together.’ This sisterly bond of understanding is reflected throughout the story, through brief memories of a ‘70s home movie’ in which the girls played in their childhood garden. The story ends in the movie memory: ‘You get up first, then pull me up, and we run off together. The garden’s empty, only the shapes in the flattened grass say that we were ever there at all.’ It is a lasting image captured on film that, for me, leaves a feeling of warmth towards the siblings’ union, yet at the same time a sense of the separation of adulthood and the pain of loss.

Many of the stories in My Mother Was An Upright Piano come with reflections on human nature, which Hershman reveals on the page in uninhibited forms. At the beginning of ‘Ankle Socks and Hair In Bunches’, the protagonist grudgingly welcomes her sister into her home. As the story unfolds we learn that the protagonist has recently lost her husband, William, and the sister has come to help her through her desperate mourning. The sister distracts the protagonist with walks and conversation. Yet expertly threaded through the story are subtle currents of grief: ‘We go out. Me, bundled up and sweating, you propelling me along. I’m paralysed by a row of ants. Or a child on a bike. You have to nudge me into motion.’ This numb sense of being is something we all experience and can relate to, making the use of second person narration unusually powerful here. When the sister eventually has to return to her own home, the protagonist panics, attacking her sister: ‘My nail catches on your cheek, there’s blood, but you don’t defend yourself. You’re crying, then I am too and we stand, locked together.’ This sisterly bond of understanding is reflected throughout the story, through brief memories of a ‘70s home movie’ in which the girls played in their childhood garden. The story ends in the movie memory: ‘You get up first, then pull me up, and we run off together. The garden’s empty, only the shapes in the flattened grass say that we were ever there at all.’ It is a lasting image captured on film that, for me, leaves a feeling of warmth towards the siblings’ union, yet at the same time a sense of the separation of adulthood and the pain of loss.

In ‘Colours Shift and Fade’, another equally moving story, Hershman explores the world of a beaten wife, through the third-person narrative of a baby. An ingenious viewpoint, yes, but it goes far further than simply being creative with perspective. The story opens with shouting, the television being turned up, and, ‘The baby is listening from his room and wondering what all the fuss is about.’ It goes on to use the senses of the child to settle the reader in this young perspective, as he distinguishes ‘between his parents and others, between smells and noises and colours and where they come from.’ By the end of the second paragraph his senses ease the reader into the reality of the situation: ‘when Mummy cries he mustn’t join in because she cries harder and for longer and doesn’t feed him.’ Hershman uses the raw and limited observation of this four-month-old child to simplify, and consequently increase, the devastation of a brutal home life: ‘He sees the dark patch around one eye shift and change, into purple then green then pink. Then one day there is a new patch, on the other side of her face, below the eye, and that changes colours too.’ The story culminates with the mother’s words, as she promises her baby that they will leave; it sums up the short journey we’ve been on, with the desperation of an adult situation seen through a child’s naïve eyes: ‘We’ll go soon. Soon. Then everything will be alright.’

Poignant final lines, such as the above from ‘Colours Shift and Fade’, are scattered through the Fictions. At the end of ‘We Keep the Wall Between Us as We Go’ – a story about ‘almost-elderly’ sisters (presumably twins) whose lives are lived so closely together one decides that they should carry a wall between them for separation – the weaker sister, and narrator, wonders ‘if, when she isn’t looking, I could crouch down behind the wall/fence and slip away quietly.’ A thought that many of us can relate to – a need to escape the things that limit us. In a similar manner, the story ‘Life Burst Out’ is about a mother and child waiting for a boat, as Life grows and blossoms. It ends with Life blowing on the tiny boat, and watching it sink, until finally, ‘Life turned around and got on with something else.’ This single line captures the sense of existence, the feeling of life growing out of control until it reaches a cataclysmic point, then, just as easily, it can take another turn.

Poignant final lines, such as the above from ‘Colours Shift and Fade’, are scattered through the Fictions. At the end of ‘We Keep the Wall Between Us as We Go’ – a story about ‘almost-elderly’ sisters (presumably twins) whose lives are lived so closely together one decides that they should carry a wall between them for separation – the weaker sister, and narrator, wonders ‘if, when she isn’t looking, I could crouch down behind the wall/fence and slip away quietly.’ A thought that many of us can relate to – a need to escape the things that limit us. In a similar manner, the story ‘Life Burst Out’ is about a mother and child waiting for a boat, as Life grows and blossoms. It ends with Life blowing on the tiny boat, and watching it sink, until finally, ‘Life turned around and got on with something else.’ This single line captures the sense of existence, the feeling of life growing out of control until it reaches a cataclysmic point, then, just as easily, it can take another turn.

By focusing in on the minutiae, and on the nature of humanity, Hershman allows her readers to peek under the layers of life for a brief moment. As a short story writer, reading these Fictions has been a real reminder to look at the world around me with fresh eyes. For me, it is her use of intrusive observation that makes My Mother Was An Upright Piano such a powerful collection. These very short stories do precisely what we want stories to do – using the bare minimum of crafted words, they stay with us long after we have finished reading.