by Benjamin Noys

Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) was an anarchist, publisher of Joyce, translator of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey into French, editor of avant-garde journals, coiner of the term ‘neo-impressionism’, possible bomb-maker, and a writer whose credo was ‘I aspire only to silence’. It therefore seems appropriate that his major work should be a collection of short news stories – referred to in French as fait-divers – that Fénéon wrote anonymously for the Paris daily newspaper Le Matin in 1906 over a six-month period. These were collected by his mistress Camille Plateel, and published after Fénéon’s death by his literary executor Jean Paulhan. If, as seems likely, Fénéon was a planter of bombs, these stories in three lines are literary bombs, or bomblets, that shock and bewilder.

Luc Sante, in his excellent introduction to his translation of Fénéon’s Novels in Three Lines, notes that Fénéon was an ‘invisibly famous’ author (Sante, 2007: viii), and it is to my regret that I only discovered him recently thanks to a friend’s recommendation. As Julien Barnes (2007) explains, Sante’s choice of title – Novels in Three Lines (Les Nouvelles en trios lignes) – is an inaccurate translation. The French ‘Les Nouvelles’, means ‘The News’, and obviously would have done in the context of the original publication, but can also mean ‘short stories’. These compressed news items are not fictions, but they are composed with all the precision of a writer of fiction, which brings out a dark humour, a tragic sense of life, or merely the banality of human existence. To use an anachronism we might regard Fénéon as an exemplar of micro-fiction avant la lettre.

The result is an endlessly quotable collection. We get, occasionally, a sense of Fénéon’s own political stance: ‘Strikers have invaded the Dion factory in Puteaux, leading the workers there astray. “Only cowards work,” their banner read.’ (Fénéon, 2007: 22) Other entries are wittily enigmatic invitations to speculation: ‘Accountant Auguste Bailly, of Boulogne, fractured his skull when he fell from a flying trapeze.’ (Fénéon, 2007: 92) What was an accountant doing on a flying trapeze? Career change, prank, or moment of madness? The majority of stories are concerned with violence: train accidents, suicides, rapes, murders, poisonings (accidental and deliberate), thefts, and car accidents, all reported in Fénéon’s deadpan, if not deliberately callous, style.

It’s certainly possible, as Luc Sante argues, to see Fénéon as a proto-modernist. After all, the French modernist poet Mallarmé, who was a character witness for Fénéon at his trial for possessing detonators, wrote that the task of the poet was to ‘purify the words of the tribe’. Surely writing news stories would offer the writer the means to do exactly that? Yet the compression and simplicity of these stories makes them accessible in a way much modernism is not. They are not openly experimental, after all they were written as actual news stories, but their subversive and disturbing edge comes from Fénéon’s ability to create what do amount to actual novels out of three lines. Consider this example: ‘The Toulouse prosecutor has launched a commission of inquiry to determine whether his strange nihilist had a good trip to Marseilles.’ (Fénéon, 2007: 106) Who is his ‘strange nihilist’ and what was the purpose of his ‘good trip’? Fénéon tantalises and mocks us as readers. He also provokes us into thinking, why do we so often read such long works? What if all stories, including our own, could be condensed into three lines?

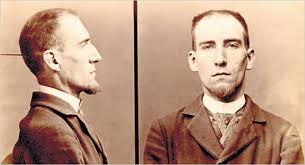

Good point! As a reader I’d say that a short novel is often a very good thing. There are also certain people in whose company a few minutes is plenty, there are others with whom I’m happy to spend almost a lifetime (with breaks!). Same goes for books. You pays yer money…. I am not sure whether Fénéon is paying deep respect to his reader’s imagination or the opposite. From the look on his face I tend to think he’s not a great one for deep respect.

As a writer I can see his point, why bother to go for all the detail, cast and drama, why not cut down on writing altogether and let the reader pad it out to suit himself or try to guess what the great and super-clever writer has in mind. Not really. I’m having you on. I can’t agree with that. No way José!

I did enjoy the examples you gave though. Perhaps because they’re so surreal and unexpected.