photo by Samuel ROSA

by Bella Whittington

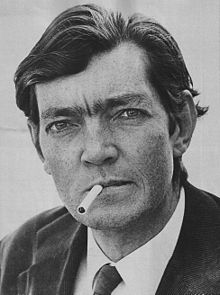

Varyingly described as a ‘magical realist’, ‘surrealist’ and ‘fantasist’, Julio Cortázar (1914–1984) is not a writer who lends himself to easy classification. It is not surprising, then, to learn that he called himself a realist: quite the opposite of the literary labels so often applied to his writing (though maybe not the sort of realist which we are used to). Of course, any writer of any literary period is subject to clumsy categorization and labelling; but it seems particularly rife when it comes to members of the Latin American ‘Boom’ generation, with ‘magical realism’ among one of the worst offenders.

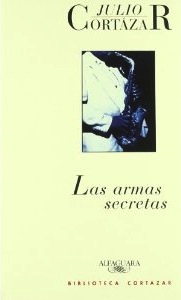

There is no hint of magical realism in ‘Cartas de Mamá’ (‘Letters from Mother’), a short story first published in Las Armas Secretas in 1959. It is a subtle, precise and peculiarly believable story about a young Argentine couple living in Paris. They work, go to the cinema, eat dinner, chat with friendly neighbours – in short, they’re no different to any other couple anywhere. However, their unremarkable, routine-driven life together is revealed as a fragile lie, easily unravelled by a reminder of their pasts; their freedom exposed as conditional; their quiet ease shown to be silent guilt. It is a single line in a single letter – one of the mother’s letters in the title – that unpicks the first thread in the flimsy fabric of Luis and Laura’s life in Paris: ‘Esta mañana Nico preguntó por ustedes’.

There is no hint of magical realism in ‘Cartas de Mamá’ (‘Letters from Mother’), a short story first published in Las Armas Secretas in 1959. It is a subtle, precise and peculiarly believable story about a young Argentine couple living in Paris. They work, go to the cinema, eat dinner, chat with friendly neighbours – in short, they’re no different to any other couple anywhere. However, their unremarkable, routine-driven life together is revealed as a fragile lie, easily unravelled by a reminder of their pasts; their freedom exposed as conditional; their quiet ease shown to be silent guilt. It is a single line in a single letter – one of the mother’s letters in the title – that unpicks the first thread in the flimsy fabric of Luis and Laura’s life in Paris: ‘Esta mañana Nico preguntó por ustedes’.

This perfectly innocent statement (‘This morning Nico asked how you both were’) develops an unsettling edge when we realise that Nico is Luis’s dead brother and Laura’s former boyfriend. The couple dismiss it as a senile mistake, the first sign that Luis’s mother might be losing her mind – perhaps she meant to write ‘Victor’, after all? The letter is an interruption of the strange, the ambiguous and the inexplicable in the ordered life they have built for themselves in Paris. It exposes their lies and undoes ‘the involuntary pact of silence’ Luis and Laura unknowingly signed when they married in the shadow of Nico’s funeral and left for Paris, shocked family and friends in their wake. Perhaps, though, the reader and the couple both think, this really was just a slip of the pen; there is still hope for a rational explanation.

Alas, the letters continue, and with them Luis’s mother announces that Nico is planning to visit them in Paris. In fact, he’ll arrive on the 11.45 train on Friday morning. Of course, we know this is impossible, and couldn’t possibly be real. Like Laura and Luis, though, we are struck by the creeping feeling that perhaps, just maybe, Nico might get off that train. This slip in our expectations is slight and disarming – it is a breach of the natural order, an unnerving inconsistency that cannot quite be rationally explained.

Inconsistency may create a worrying atmosphere in ‘Cartas de Mamá’, but Cortázar’s narrative style does not falter. This is a subtle, tightly constructed and exquisitely restrained short story. Threaded with hypotheses, rhetorical questions, conditional sentences, asides and different narrative voices, this story weaves a claustrophobic net of worry, indecision and pressing guilt that lures us into sharing the same unstable state of mind as Luis and Laura. The very idea of Nico is suppressed in their lives, and Cortázar reflects this by containing his mention in mamá’s letter for a good one thousand words. The many asides – ‘No, it didn’t matter much to him (Didn’t it matter much to him?)’ – serve to muddy the narrative voice: is it Luis who is acknowledging his own pretence, or mamá, or Nico, or the narrator? In turn, long sentences filled with different voices, the repetition of ‘perhaps’, parentheses and conditional sentences reveal the inherent self-delusion behind the artifice of their lives – ‘And this very afternoon he would write to mamá without making the slightest reference to the whole ridiculous episode (but it wasn’t ridiculous) and then he would be brave and talk to Laura (but he wouldn’t be brave and he wouldn’t talk to Laura).’

Luis and Laura are – by appearances, at least – the protagonists of the tale. Yet poor, dead Nico and deluded, far-away mamá become gradually ever more present. One of the most striking metaphors in this story is that of an increasingly complex game of chess – a game initially played by only Luis and Laura in their sparse and charged exchanges, until later, alarmingly, they are joined by mamá and Nico. The Parisian life led by Luis and Laura is revealed as just a game – but a game whose rules are constantly changing. ‘Peón cuatro rey, peón cuatro rey. He realized that the game was continuing, that it was his turn to make a move. But there were three players in this game, maybe four.’

The most disturbing aspect of ‘Cartas de Mamá’ is just how recognisable the characters’ feelings are. We can imagine ourselves in Laura and Luis’s position; we can imagine feeling the uncomfortable, eerie fear they each experience waiting for Nico at the station, or realizing that Nico has always been there, the dead brother and lover in their bed and in their lives. Their apartment – ‘big enough for two, thought out exactly for two’ – begins to feel like a tightening fist, everything ‘narrower’ and claustrophobic. This is Cortázar’s forte – he creates a wider, ambiguous reality that represents the complexity of human – and, therefore, our own – experience. Cortázar may have described himself as a realist, but he is a nuanced, expressive realist working within a wider spectrum of reality than the term would lead us to expect.

The most disturbing aspect of ‘Cartas de Mamá’ is just how recognisable the characters’ feelings are. We can imagine ourselves in Laura and Luis’s position; we can imagine feeling the uncomfortable, eerie fear they each experience waiting for Nico at the station, or realizing that Nico has always been there, the dead brother and lover in their bed and in their lives. Their apartment – ‘big enough for two, thought out exactly for two’ – begins to feel like a tightening fist, everything ‘narrower’ and claustrophobic. This is Cortázar’s forte – he creates a wider, ambiguous reality that represents the complexity of human – and, therefore, our own – experience. Cortázar may have described himself as a realist, but he is a nuanced, expressive realist working within a wider spectrum of reality than the term would lead us to expect.

Part macabre ghost story, part depiction of a bourgeoisie life built on falsity and guilt, ‘Cartas de Mamá’ reveals a present undone by the past, and leaves us disarmed by its effortless complexity.

~

Extracts from the text have been translated by Bella Whittington.

~

Bella Whittington studied Modern Languages at Oxford University, graduating in 2010. Having lived in Spain for a year, she now works at a publishing company in London and writes the occasional review.