photo by Alicia Calvet

A Quiet Voice Talking

by Amanda Oosthuizen

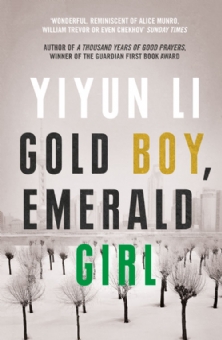

The stories in Yiyun Li’s extraordinary collection Gold Boy, Emerald Girl, tell of a China emerging into the 21st century. Her characters are fascinating and the stories are a captivating window into day to day life in China. If you are interested in the details of how people have survived all these years in the People’s Republic, before the social and economic reforms of the last twenty years, you can’t do better than read this book. But there’s more to it than that.

The stories are told in a quiet, low-key, thoughtful way: never melodramatic or even particularly dramatic. Neither do you hear the voices of individual characters especially clearly, as Li consistently employs a distant third person narration. Often, the stories sound like folk tales and fables with ancient sayings, old folksongs, and almost forgotten traditions all making an appearance. Perhaps, I thought as I read, Li’s saying that the decades of hard line Communism, the rule of the iron fist, are a terrifying blip on the ancient Chinese cultural landscape. Maybe.

Li describes changing times: the property boom, adoption, children returning from the US. And the situations themselves are often intriguing: a wealthy old woman shelters women in trouble in her mansion; a group of elderly women become famous private investigators specialising in extra-marital affairs. Interesting subjects, yes, but I found the stories themselves depressing, largely because of the monotone voice. Li’s sentences are plain, and the statements are simple, as with the opening of ‘Prison’ where: ‘Yilan’s daughter dies at sixteen and a half on a rainy Saturday in May, six months after getting her driver’s licence.’

Yet as I thought about the voice, I began to see that I was missing the point. Many of Li’s characters have suffered deprivation, emotional or economic, or both; perhaps it wasn’t the cumulative voice of hopelessness and misery I was listening to, but the voice of the oppressed. Li is telling the stories of people who have been forced to hide their individuality. We know that during the first forty years of the People’s Republic of China life was difficult, impossibly so for many. Creativity had to follow strict rules; families were small and emotionally undernourished; many people lived in terror. Li is showing how years of oppression, and the fear of violence and other repercussions for refusing to conform, have made people quietly introverted and psychologically repressed.

Yet as I thought about the voice, I began to see that I was missing the point. Many of Li’s characters have suffered deprivation, emotional or economic, or both; perhaps it wasn’t the cumulative voice of hopelessness and misery I was listening to, but the voice of the oppressed. Li is telling the stories of people who have been forced to hide their individuality. We know that during the first forty years of the People’s Republic of China life was difficult, impossibly so for many. Creativity had to follow strict rules; families were small and emotionally undernourished; many people lived in terror. Li is showing how years of oppression, and the fear of violence and other repercussions for refusing to conform, have made people quietly introverted and psychologically repressed.

As Robert Coover stated at last year’s Small Wonder Festival, during which he and Yiyun Li discussed their work (see the Thresholds podcast), ‘the writer has to strive for the truth as it concerns the metaphor he’s working with. If it’s a dark subject, a dark voice is likely to be the best for the job.’ The voice in Li’s work is not particularly dark or angry, but any lightness or optimism that may be present is shaded in thoughtful grey tones. In ‘The Proprietress’ a reporter interviews Mrs Jin about her rescue home for women. As they discuss the elderly resident, Granny, and her friendship with the young Susu, Li’s pensive voice is apparent: ‘Granny was a bad influence, a woman who let the memory of a short marriage become the only life she knew.’

You sense the historical burden her characters are forced to carry but contrary to the assumptions of many westerners, they are not enticed by the flashy, new world. Earlier in ‘The Proprietress’, the reporter decides to write her story about Mrs Jin : ‘An impressive story it would be, she told Mrs Jin, an important one about sisterhood that would reach all the female readers of the magazine. The reporter’s talk was like her big-city clothes, fancy but laughable.’ Li’s characters do not seek to replace the old regime of oppression and poverty with the new ideology of western consumerism. Instead, the characters are quietly clinging to something else, holding something for themselves, finding their own way. That’s the point, I think.

On the whole, Li’s protagonists are troubled victims of the past: the Communist regime having curtailed their ambition in one way or another. In the first story, ‘Kindness’ – the one Li reads on the Thresholds recording – we read of a young girl, Moyan, who finds herself in the People’s Liberation Army, struggling to find a voice, always resorting to Communist slogans to hide her emotional life: ‘Every Sunday night, we read our weekly reports at the squad meeting. I always began mine that in the past week I had kept up my faith in Communism and my love of our motherland.’ When an officer orders Moyan to sing, she tries, but finds she has no voice even when she wishes with all her heart to obey the order. Ultimately, she never finds the courage to fight her way out of her past but clings to her memories and a love of literature (I’m not giving anything away here, because we know this from the beginning of the story). As Li says: ‘the chick cannot be returned to the shell’. I think this image suggests that there is no going back; as we mature as individuals, we set ourselves free from our past to make the journey into the future, alone.

This metaphor of rebirth and aloneness runs throughout the collection. Li talks of how her stories start a lonely journey when she sends them out into the world, so she has built an ally for them with those of William Trevor. Her stories, she says, talk to Trevor’s, and find friends in his stories – they are intended to be part of a dialogue. The title story in this collection was written especially to talk with Trevor’s story ‘Three People’ (The Hill Bachelors). Trevor’s story is about an aging father, a middle-aged daughter and a man who the father hopes will marry the daughter. Li’s ‘Gold Boy, Emerald Girl’ is about an aging mother, a middle-aged son and a woman who the mother hopes will marry the son. Neither liaison works as planned.

Similarly, Li’s story ‘Kindness’, narrated by a middle-aged woman who decides not to love anyone, is inspired by Trevor’s novella ‘Nights at the Alexandria’ in which, a middle-aged man also leads a solitary life. There are many parallels to be found in the themes of the two authors’ stories, but more importantly Li aligns her writing with Trevor’s in her aim not to over-dramatise. The big dramas occur in the past, or are touched on only lightly in the present. It is through the smaller events that her characters are given space to live. Perhaps it is the universality of the small event that enables these writers to communicate across continents.

Similarly, Li’s story ‘Kindness’, narrated by a middle-aged woman who decides not to love anyone, is inspired by Trevor’s novella ‘Nights at the Alexandria’ in which, a middle-aged man also leads a solitary life. There are many parallels to be found in the themes of the two authors’ stories, but more importantly Li aligns her writing with Trevor’s in her aim not to over-dramatise. The big dramas occur in the past, or are touched on only lightly in the present. It is through the smaller events that her characters are given space to live. Perhaps it is the universality of the small event that enables these writers to communicate across continents.

The stories in Gold Boy, Emerald Girl inhabit the countryside, the city, the army, the successful, the deprived and the lives of people who have left China and returned. Li’s characters are discovering this new, modern world and they are absolutely true and recognisable. They are people with whom one can converse, people bravely creating their own paths. These are masterful, beautiful stories and are, for an insight into lives led in a far off land, absolutely wonderful. Read them.

Amanda, we’d LOVE something on the Russians and the short story – would be fascinating. – or on a fav Russian story writer.

Thanks Alison. I’m heavily into the Russians at the moment. Has any other ‘nation’ such a wealth of short stories? Particularly interesting since they’ve had to write with the censor on their backs or at their throats for a hundred years or so.

I highly recommend this ‘We Recommend’! Many thanks, Amanda. It really captures what’s special about Yiyun’s stories, and it’s a rich read in its own right. Please send us more where this came from!

Thanks Dora. The podcast is really interesting, particularly if you’ve read the stories. I’ve bought the Robert Coover book because I thought he sounded pretty amazing on the podcast. In fact, when I come to think about it, I’ve bought many books because they’ve been recommended here, including the brilliant ‘Short Circuit’, Vanessa Gebbie’s guide to the short story. It shows so many approaches by very different writers and has given me lots of ideas. Worth every penny! Also, someone on Thresholds recommended the NYCMidnght competition where you have to write to certain prompts within a time and word limit and that seems to have taken over my life at the moment because I seem to have got through to the second round somehow or other. It’s a scary competition. I’ve posted my stories on my very secret blog! http://amandaoosthuizen.com/ All comments more than welcome.

Good luck with your writing.

Thanks Amanda. Loree Westron wrote about the NYC Midnight competition and I think even won! I remember reading the article and yes, participation sounds pretty daunting. I don’t think I could have participated last year but I’m feeling a little more confident in my writing abilities so time-willing, I may give it a go next time they have another contest.

Vanessa Gebbie’s book sounds wonderful so I may have to buy it. I need all the help I can get. I also visited your website and read some of your work, including your latest competition entry. It’s wonderful!

I would also like to post (secretly of course) some of my work to get some comments but how do you make sure it’s not out there for everyone to read? I am so confused as to the question of what constitutes work that’s published versus unpublished work. Many ezines, etc. do not want any work that already posted on the internet as they consider the work published. My feeling is that it takes me so long to finish a piece I want something to come out of it, if you know what I mean!

I too have also bought books from those authors who’ve participated or I’ve heard of, from this blog. Being away from Academia and the Publishing world for a long time, this website has been a great refresher course.

Time willing I’ll run over to your blog to see how well you are faring with the contest. Good luck!

Thank you for taking time out of your novel writing to write this wonderful piece. I haven’t had a chance to listen to Yiyun Li’s podcast yet, but will do so shortly. Like you I am pressed for time, but keeping up with the current short story writers is a must as that will only make one a better writer. I am so happy that I have a place to come to that will allow me to experience and get to know these wonderful, new writers. Thank you Thresholds for the umpteenth time!

Good luck with your novel.