photo by Charles Strebor

*

Watch Your Step: The World of Michel Faber

by Miles Salter

Watch your step. Keep your wits about you; you will need them.

The first words of the novel The Crimson Petal and the White are a good introduction to Michel Faber’s impressive oeuvre. Published in 2002, it is his most famous work: a story of business, prostitution and family upheaval in Victorian England – a story that is brutally honest in its account of the darker side of London Society in the 1880s. Faber has also written The Apple, a book of stories based on the characters in The Crimson Petal and The White, and The Fire Gospel, a book that satirises religion, media, the internet and publishing.

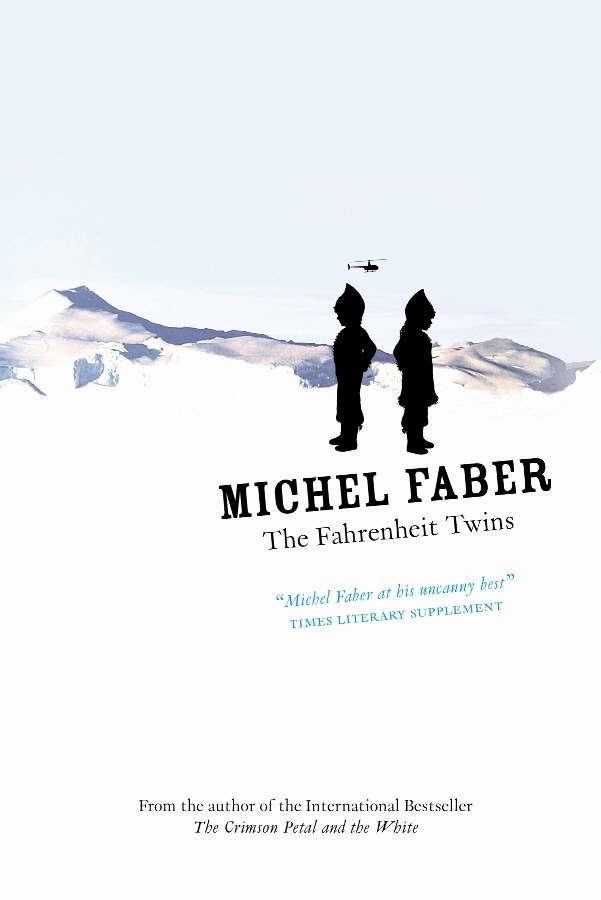

But Faber’s short stories are arguably his most beautiful and unsettling works. To date, he has published two volumes: Some Rain Must Fall and The Fahrenheit Twins.  Both collections display elements of surrealism, but the stories always return to the theme of the human condition and relationships between people.

Both collections display elements of surrealism, but the stories always return to the theme of the human condition and relationships between people.

Faber is Dutch by origin, but, according to an article in The Scotsman, he has no memory of the first seven years of his life in the Netherlands. He knows, though, that his childhood was traumatic: “I don’t remember any of it,” he says. “But other family members have since filled me in on things that were going on in my family and I’m sure it wasn’t a healthy environment.”

Faber’s imagination is enviable; he explores an incredible array of situations and characters. These include a teenage boy obsessed with playing video games, a family travelling on a train, squalid Victorian London, a sci-fi dystopia, an alcoholic nun contemplating suicide, a teenage boy fantasising about sex whilst his sister has an abortion, a thrash metal band on tour, a deaf woman working in a sex shop… One particularly admirable and original piece of writing comes in the story ‘Under the Skin’. When Isserley, the female protagonist, is about to be sexually assaulted by an aggressive male, Faber inserts a passage from the male’s point of view and, instantly, the entire timbre of the writing changes. It’s a masterful use of empathy and language. Another instance is ‘The Safe House’ – which won second place in the inaugural National Short Story Award in 2005 – the darkly unsettling story of a man who makes his way to the house in question, which is populated by people who are missing from society. It’s a sideways view of compassion, but nonetheless compelling and disturbing.

Thomas Merton, the Catholic monk and writer, once said that he wanted to write a book that contained ‘everything’. I was curious about Faber’s ability to seemingly take any aspect of the world and write about it with insight and understanding, and so, whilst emailing him for a possible article in 2007, I asked him if he agreed with Merton’s ambition to write about ‘everything’. His response was as follows:

I don’t think my books contain everything, but I must admit I’m struck by how unambitious most modern novels are. There is a prevailing sense that if a book has a strong theme and maybe one character with some depth, it’s already doing plenty and we shouldn’t expect any more. There are even people who think that if a book tries to succeed on too many levels it becomes messy and difficult to digest. I’ll point out to someone that a book they’ve been praising as magnificent fails to offer credible characters or deep emotional engagement, and they’ll say, “But that’s not what this book is about, you can’t have everything.” The whole point of fiction should be to allow the reader to experience life from inside different people’s skins. I can’t understand why any intelligent person would want to read a novel where the only vaguely credible character is the one that’s based on the author, and all the others are either multiples of the author or cringe-inducingly false constructs. In my own work I do try to make all the levels work.

One of these ‘levels’ Faber refers to is violence. His short stories are habitually disturbing and upsetting – in ‘Under The Skin’ people are paralysed and mutilated – but the upset often comes from situations that seem so familiar, even domestic. In The Fahrenheit Twins, a story called ‘The Smallness of the Action’ offers the following, remarkable line: ‘On Wednesday morning, in a moment of carelessness, Christine dropped her baby on the floor and broke him.’

When I emailed Faber, I also asked him about his attitude to violence. He commented:

A huge proportion of storytelling, especially nowadays, involves violence. Movies and video games are pretty much ruled by a gangster/monster/serial killer aesthetic. Bloodthirsty crime novels, which used to be considered pulp rubbish unworthy of serious notice, are now being reviewed seriously. So there’s a lot of it about. But most violence is used only as a “special effect”, to shock the reader, sicken them, or jolt them out of their seat. I’m interested in exploring what violence really means to vulnerable individuals like you and me. For this reason, the violence that occurs in some of my stories may affect the reader more deeply than the (far more spectacular) violence they see elsewhere. If someone in a movie gets their brains shot out by a sudden gunshot, that may startle you for a second, but it will affect you much less than implied violence [that is] “closer to home”.

Some of the violence in the stories, especially that which is depicted in the story ‘The Fahrenheit Twins’, may spring from a lack of connection that humans feel for each other. Writing in The Guardian in 2005, at the time The Fahrenheit Twins was published, the critic M. John Harrison noted of the characters:

Pain, psychological and economic, has dissociated them; dissociation renders them invisible to themselves and unavailable to each other. The kind of pain you feel as spiritual anaesthesia is cumulative; its cure, more often than not, is to buy rather than do.

Perhaps Faber sees the cracks in consumerist culture. He certainly avoids television. When I asked him to complete the question ‘TV is…’, he wrote the following:

Best avoided. In theory you could educate yourself with TV, choosing only the most enlightening programs and the most superb movies. In practice, people aren’t that disciplined; they get into the habit of watching whatever’s on, and they ingest a shitload of piffle. As a non-TV watcher, I find conversations with TV watchers quite tiresome. It’s like talking to drunks while you’re sober, or to stoners while you’re straight.

The Guardian‘s Libby Brooks has commented that Faber is ‘a writer so reclusive that he makes the Loch Ness Monster look like an extrovert’. Certainly, Faber often avoids public appearances:

I’ve largely withdrawn from my career as a public person. I say no to almost all offers, don’t go to book festivals any more, etc… I’ve resolved to avoid [these events], because you meet lots of people in the literary “industry” and you smell their hunger for success or attention or status, and I hate to be reminded of all that.

~ Email from Michel Faber, June 2007

His reclusiveness is strange, given his ability to empathise with people in so many different and varied situations, but perhaps he has given himself to the role of observer.

His reclusiveness is strange, given his ability to empathise with people in so many different and varied situations, but perhaps he has given himself to the role of observer.

In 2011, The Scotsman published an interview with Faber, around the time that the BBC were due to screen The Crimson Petal and the White. The journalist who conducted the interview found Faber to be forthcoming and open, even discussing the terminal illness of his wife, Youren. But in the interview, Faber disclosed that he found travelling and meeting new people traumatic: “One of the things my success as an author has forced me to face is how… obsessive I am.” This obsession comes through in his vast collection of music and in his writing – as a teenager he wrote hundreds of short stories, but burnt them, each time trying to do better. He began writing The Crimson Petal and the White in his late teens, as he told me in our email exchange:

I was 18 or 19. I wrote about a hundred pages, then my first marriage got very time/energy-consuming and I didn’t write any more for years. I finished it when I was about 27. Then wrote a second version, and a third. It was fun and, yes, exhausting at times. As for thinking it might never come out, I actually ASSUMED it would never come out; I had no intention of submitting it to a publisher. I didn’t submit any of my work for publication. I just wrote it and put it away.

It was Youren, Faber’s second wife, who eventually convinced him that books should be read. They met when he was living in Melbourne, Australia. Faber had rented a room in her house and she was the one who proposed a move to the Highlands. She encouraged Faber to type up his stories and send them out – an early moment of success took place when he won the Macallan/Scotland on Sunday Short Story Competition in 1996. And his successes grew from there.

Faber’s writing is compelling and he is one of the best writers the world has at the moment. For some, his work will be unsettling, even horrific, but for others it is full of rich rewards. If you haven’t read his stories yet, when you do, remember: watch your step.

~

Miles Salter is a writer, musician and storyteller based in York. He writes poetry, fiction and journalism. Miles’ second poetry collection, Animals, will be published by Valley Press in September 2013 and he is currently writing a comedy adventure story for children. Miles is also Director of York Literature Festival. He likes the smell of Marmite, the sound of guitars and the poetry of Philip Larkin. He wishes his papers were in order.