photo by Dave King

by Séamus Duggan

Sometimes it seems that a short story can embed itself deep inside the memory, into

crannies that novels can’t fit. Many of the stories that have managed to establish themselves in my mind depict an absurd world where actions are dictated by chance and prejudice, and the frailty and insignificance of human life are in the foreground.

The stories that particularly push themselves upon me are ‘The Downfall of Fascism in Black Ankle County’ by Joseph Mitchell, ‘Hunters in the Snow’ by Tobias Wolff, and ‘The White Bitch’ by Liam O’Flaherty. All focus on the absurdity and frailty of life, and there is little evidence of heroes or their journeys in any of them. Somehow these stories encapsulate my relationship to the short story and much of my own attitude to life. They have stood up to many readings and will stand up to many more.

*

These stories all have something of the dream about them – an instantaneous light that it is then suddenly extinguished – and they contain a true sense of the world’s absurdity: a drunkard Klansman planning to teach some bootleggers a lesson; a peasant putting life and limb at risk for a bitch that he had, just a few minutes earlier, tried to drown; a punch line turned back on the joker. The stories are set in isolated worlds. Indeed, one is written in a world that consists of just two people, a dog, a cliff, a boat and the sea. However, this is no barrier to the stories’ ability to comment on the human condition.

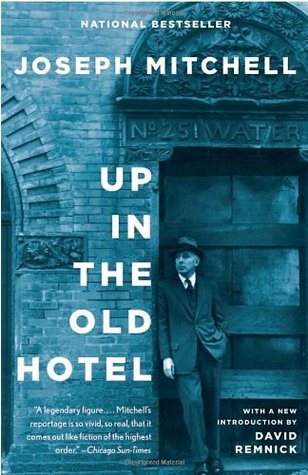

Written in 1938, Joseph Mitchell’s ‘The Downfall of Fascism in Black Ankle County’ is an early piece of anti-fascist writing, deploying the arsenal of the satirist against the posturing of Mussolini, Göring and the whole fascist crew. However, they are only mentioned in the opening line:

Written in 1938, Joseph Mitchell’s ‘The Downfall of Fascism in Black Ankle County’ is an early piece of anti-fascist writing, deploying the arsenal of the satirist against the posturing of Mussolini, Göring and the whole fascist crew. However, they are only mentioned in the opening line:

Every time I see Mussolini shooting off his mouth in a newsreel, or Göring goose-stepping in a rotogravure, I am reminded of Mr Catfish Giddy and my first encounter with Fascism.

After that we are back in the world of the narrator’s youth: the year 1923, in Stonewall, North Carolina, the time and place where ‘Mr Giddy and Mr Spuddy Ransom organized a branch of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, or the Invisible Empire, which spread terror through Black Ankle County for several months’.

Mitchell revels in the absurdity of the Klansmen. Their two leaders are a drunk and a religious fanatic; one a tobacco salesman, one campaigning for potatoes to be grown instead of tobacco. The children spy on and laugh at their activities, and know full well who the ‘bedsheets’ are. When the head Klansmen get white sheets for their mules, the sight of these be-sheeted asses frightens the other mules, unseating many Klansmen and causing them to stick to automobiles from that point onwards.

We know from the first sentence that their history will be short, but the event that brings it to an end is not heroic but even more absurd than what has come before. Three Irish bootlegger brothers are set to be targeted so they get hold of some dynamite to protect themselves. When the Klan fail to arrive, the three brothers, high on their own supply, detonate the three charges of dynamite, blowing huge holes in the ground and almost destroying their own house and holdings. But the damage and the holes are sufficient to convince the Klansmen not to ride any more and they disband.

The whole story reads to me as a refusal to see Fascism as legitimate. The down-home humour is perfectly pitched. Giddy and Spuddy may be as laughable as their names, but they are shown as capable of perpetuating horrific cruelty upon the powerless. It also suggests that cowardice is a fundamental element of prejudice as people try to hide from their own failings by attacking traits of other people, even when those traits are also their own.

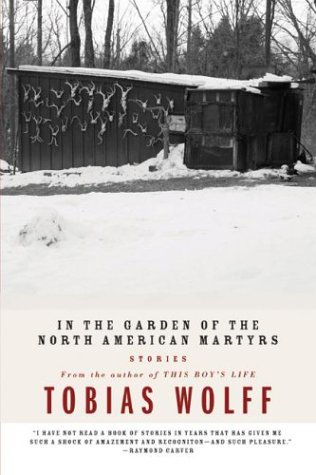

‘Hunters in the Snow’, written by Tobias Wolff in 1982, seems to me to sit easily beside Mitchell’s story. Three men – Kenny, Frank and Tub – head out hunting for the day. Similarly to Mitchell’s Klansmen they are, one thinks, using it as an excuse to get out of the house.

‘Hunters in the Snow’, written by Tobias Wolff in 1982, seems to me to sit easily beside Mitchell’s story. Three men – Kenny, Frank and Tub – head out hunting for the day. Similarly to Mitchell’s Klansmen they are, one thinks, using it as an excuse to get out of the house.

The trio is like a comedy act, with Tub as the fall guy. The story opens with him waiting in the cold and then the others arrive an hour late and drive the van up onto the pavement to force him to scramble out of the way. After they return from hunting, Kenny shoots a couple of objects, then shoots the landowner’s dog. In a final move, he points the gun at Tub, pretending to have gone off the rails. Tub, spooked, shoots Kenny. But it turns out that Kenny had, in fact, been asked to shoot the old dog by the landowner.

Much of the story consists of the drive to the hospital in freezing weather as Kenny bleeds to death. His behavior before the shooting leaves us with little sympathy. And his death allows the others to connect in a way they never could when Kenny was around. Frank admits to having fallen for his babysitter and Tub confesses that his weight is not a result of ‘glands’ but of secret binge eating.

Although both of these stories are absurd, they also seem to take place in a somewhat comforting universe. The Klan are disbanded and Kenny reaps what he sows. The final story is less comforting, though, and it is perhaps no coincidence that I see it as being, at least partly, about the act of writing.

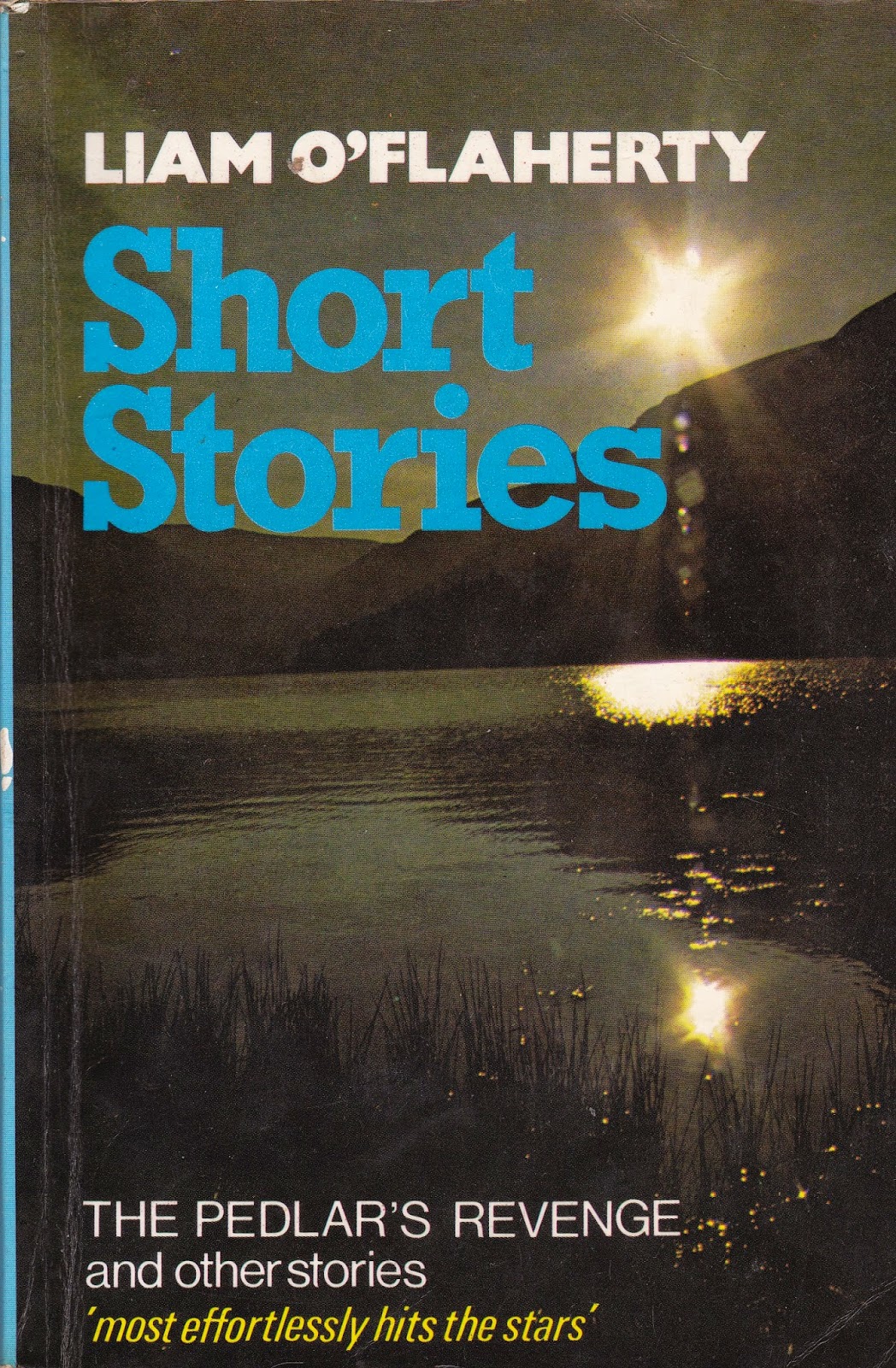

In ‘The White Bitch’ from 1924, Liam O’Flaherty tells, in around three pages, the story of a couple who decide to get rid of their dog because they can’t afford a license. To this effect they lead the dog to the edge of a cliff and, after some arguments, throw him off. However, the dog does not die and the couple change their minds and rescue him from the sea. The woman says that she will sell some material she has set aside for a dress to pay for the license. It is at once throwaway and mythical.

In ‘The White Bitch’ from 1924, Liam O’Flaherty tells, in around three pages, the story of a couple who decide to get rid of their dog because they can’t afford a license. To this effect they lead the dog to the edge of a cliff and, after some arguments, throw him off. However, the dog does not die and the couple change their minds and rescue him from the sea. The woman says that she will sell some material she has set aside for a dress to pay for the license. It is at once throwaway and mythical.

In O’Flaherty’s story the dog is white with a couple of black spots, which I see as a metaphor for the blank page itself. And the sea, well it could be the wastepaper basket. There goes another page. No wait, there might be something in it. Or maybe there isn’t, but what does that matter. The story seems almost a cosmic joke on the whole idea of stories.

The absurdity of the situation reminds me of Samuel Beckett’s writing, and the relationship, blasted by drink and mutual disappointment, seems to find an echo in the work of Raymond Carver. O’Flaherty creates a series of linked yet meaningless events where the characters expend a lot of effort and emotion simply to get back to the same place that they started.

*

There is something that the short form allows to happen in these stories: it focuses our minds on the act and doesn’t detract from it by elaboration, or extraneous back-story or plot. It then seems to amplify that act and the echo reverberates for longer than it would were the incident merely part of a longer work.

It also seems to be the perfect vehicle for an absurdist viewpoint. If life is absurd, surely a novel is hard to justify, but a short story can pretend it is just a moment’s work, a fiction belied by the tautness and balance displayed in all of these stories.

I used to write stories for my brother when I was younger. He would be given a title and told to write an essay of so many words for the next day and would pay me 50p to write them. I have never enjoyed writing so much since. The anonymity freed me. I played it for laughs and, I believe, the stories got them. Perhaps I need to embrace the absurd again. After all, it is what attracts me as a reader.