photo by B.C.Lorio

by Ruba Abughaida

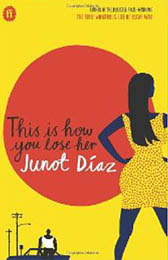

Junot Diaz’s This is How you Lose Her is a collection of short stories that is compelling in both its style and characterisation. In a deft move, Diaz links each of the stories – the majority of them coming from a Latin American and Caribbean community in the United States, and all of them telling the story of Yunior, a Dominican American living in New Jersey.

Diaz explores different times in Yunior’s life – from his teenage years to adulthood, and through his trips home to the Dominican Republic and back to New Jersey. He gives us snapshots of vital events in Yunior’s world, but he also weaves into the narrative the stories of other characters in the community, peppering them with untranslated Spanish sentences, and ultimately revealing how the stories are linked. We are introduced to laundry workers in a hospital, families with missing fathers, young boys in the community, mothers and sons, and doomed relationships.

Diaz begins the collection with a story title that sparks hope: ‘The Sun, The Moon, The Stars’. He quickly draws us into the narrative with the first-person voice of Yunior:

I’m not a bad guy. I know how that sounds – defensive, unscrupulous – but it’s not true. I’m like everybody else: weak, full of mistakes, but basically good. Magdalena disagrees though. She considers me a typical Dominican man… See, many months ago, when Magda was still my girl, when I didn’t have to be careful about almost anything, I cheated on her with this chick who had tons of eighties free-style hair.

By using the vernacular to bring Yunior’s voice to life, Diaz gives us a deep glimpse into the community. Through voice and dialect, he allows us to be a part of it in a way that most of us have never been. We are swept along in the rhythm of the dialogue, we hear it clearly and easily, and, at times, we are electrified by it.

By using the vernacular to bring Yunior’s voice to life, Diaz gives us a deep glimpse into the community. Through voice and dialect, he allows us to be a part of it in a way that most of us have never been. We are swept along in the rhythm of the dialogue, we hear it clearly and easily, and, at times, we are electrified by it.

Diaz’s precise attention to the spoken voice extends to the point where we see a slight change in Yunior’s vernacular when he enters the work force, reflecting his environment and even perhaps his perceived status in it. For instance, the Yunior in an early chapter of the book describes, in a free and easy manner, an encounter during a night out:

I met these two rich older dudes drinking cognac at the bar. Introduce themselves as the Vice-President and Barabaro, his bodyguard. I must have the footprints of fresh disaster on my face. They listen to my troubles like they’re a couple of Capos and I’m talking murder.

While towards the end of the book, the older, professional Yunior speaks in a more restrained or even subdued voice:

March you fly out to the Bay to deliver a lecture, which does not go well; almost no one shows up beyond those that were forced to by their professors. Afterward you head alone to K-town and gorge on kalbi until you’re ready to burst. You drive around for a couple of hours, just to get the feel of the city. You have a couple of friends in town but you don’t call them because you know they’ll only want to talk to you about old times…

Since it is Yunior himself who is usually narrating, we are completely reliant on his interpretation of events; his understanding of a situation becomes ours. Experiencing his life with him becomes, in a way, surreal, and we make assumptions very early on about whether he’s reliable or not. In the end, we understand that he is presenting the truth as accurately as his point of view allows.

In This Is How You Lose Her, Diaz does not use quotation marks to frame the dialogue – an unusual, yet extremely effective approach. This break with standard lay-out lets the writing take on a fluid, ‘slipstream’ quality so that everything becomes a seamless flow of thought and voice, with nothing to jar or break the momentum of the story. Yunior carries on an intimate discussion with us, about everything happening around him; he takes us into his home, involves us in family issues, and opens up his love life to us. But under each of these seemingly every day actions runs the current of larger issues: immigration in the United States, its failure to integrate communities, language barriers, poverty, the dearth of support systems, the characters’ difficulties and triumphs. Throughout the collection, there is a longing to go back to something that is buried under the reality of each of the characters’ lives. The tension and energy of this longing rises up from the community as a whole and simmers collectively across it.

Diaz records and reports the experience of a community that is not often heard in mainstream discussions, and he does so with honesty and beauty. He describes this world to us directly:

I’d tell you about the shanties and our no-running-water faucets and the sambos on the billboards and the fact that my family house comes equipped with an ever-reliable latrine. I’d tell you about my abuelo and his campo hands, how unhappy he is that I’m not sticking around, and I’d tell you about the street where I was born, Calle XXI, how it hasn’t decided yet if it wants to be a slum or not and how it’s been in this state of indecision for years.

As Yunior’s life progresses, we go along for the ride. We watch him struggle. We sense his loss and confusion, his resentment and resignation, and also his anger at himself and others for the life that he has. At times, we witness his happiness; at other times, the comedy or absurdity upon which his world teeters. He grows as a character, assessing his past mistakes and taking stock, and inching his way onto the path to a kind of redemption. He is likeable because he is someone who is constantly trying to come to terms with his actions. He shows us his vulnerability. He wants to do the right thing and to fix what he did wrong. But he is always up against the deep grooves of past behaviour, and those patterns continue to lead him to behave in the same way over and over again.

The writing aims to be raw and at times the language is coarse and graphic, but it is ultimately so real that it takes on its own kind of urgency. Reviewers have said that the stories are about love in its many forms. Yunior tells us that ‘Real love is not so easily shed’, but the stories are also about a love that reaches inwards; a love that allows one to accept oneself.

The writing aims to be raw and at times the language is coarse and graphic, but it is ultimately so real that it takes on its own kind of urgency. Reviewers have said that the stories are about love in its many forms. Yunior tells us that ‘Real love is not so easily shed’, but the stories are also about a love that reaches inwards; a love that allows one to accept oneself.

By the last story, ‘The Cheater’s Guide to Love’, there is a sense that we have all been through something big together. It’s not just that the reader that has come to trust Yunior, but also that Yunior now trusts the reader. He appears to be speaking to us as friends, writing from a second-person point of view, and saying: ‘Your girl catches you cheating. (Well, actually she’s your fiancée, but hey, in a bit it so won’t matter.)’ By this stage in the collection so much has changed for Yunior, yet at the same time, Diaz brings us full circle, showing us that Yunior is still, unforgettably, Yunior.

~

Junot Diaz’s story ‘Miss Lora’ is currently shortlisted for The Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award – the world’s largest prize for a single short story.