photograph by Constantin Jurcut

by Amanda Oosthuizen

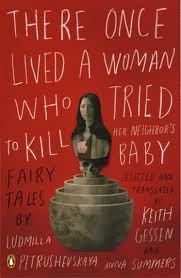

From the moment I began reading the first story in There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbour’s Baby, I was compelled to read with the same desperate energy that drives Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s characters to survive. These are fantastical stories, apocalyptic urban folk tales, sinister, surreal. This is optimism in the face of hopelessness as Petrushevskaya explores the impossibility of being alive. It is this optimism that fascinates me.

The darkness in Petrushevskaya’s stories prevented them from being published in the Soviet Union. Yet she continued to write, and in 2009 the collection was published by Penguin Books in the US. She was 50 when her first book came out, and she is now hailed as the finest living Russian writer. Although her stories are dark, they are about seeing things through to the end, before they rebirth and emerge into the light.

The collection is divided into four sections: Songs of the Eastern Slavs, Allegories, Requiems and Fairy Tales. It begins with a series of very short stories that crank up your reading engine in preparation for the longer ones. Petrushevskaya says that on occasions she uses traditional plots and develops them in her own way, and at other times she makes her own plots sound like folk lore. Many of these stories give this impression right from the first sentence: ‘There once was a woman whose son hanged himself’ (‘The Miracle’). ‘There once was a man who couldn’t find his children’ (‘The Father’). Many of the shorter stories tell of nameless archetypal characters, but my four favourites are more developed and transport us into worlds that shift at every step.

The collection is divided into four sections: Songs of the Eastern Slavs, Allegories, Requiems and Fairy Tales. It begins with a series of very short stories that crank up your reading engine in preparation for the longer ones. Petrushevskaya says that on occasions she uses traditional plots and develops them in her own way, and at other times she makes her own plots sound like folk lore. Many of these stories give this impression right from the first sentence: ‘There once was a woman whose son hanged himself’ (‘The Miracle’). ‘There once was a man who couldn’t find his children’ (‘The Father’). Many of the shorter stories tell of nameless archetypal characters, but my four favourites are more developed and transport us into worlds that shift at every step.

In ‘A New Soul’, a man is lost between two worlds. One minute he is desperately rushing to catch a plane in order to save his son from being drafted into the army. He makes it into the crowd of waiting boys, but in the next minute ‘The father takes hold of his son’s sleeve, begins to scream and wakes up in the United States, in the form of an unhappy immigrant named Grisha…’

This sudden transportation sounds like a nightmare, and Petrushevskaya bases much of her mystical work on dreams. These are often only thinly disguised and can at times seem so familiar that one hears one’s own words attempting to retell a nightmare that flits illogically. ‘Somehow or other, one day he began to talk in an impoverished television language with a crazy black man…’

Grisha eventually returns to Russia and remarries his old wife. They recognise each other but not as the people they were: ‘It was a genuine double recognition: two souls met and didn’t know it.’

There is no explanation or reason for this. The story ends as the mother ‘flew off with her new husband to the place where her first husband’s soul now lived – and no one ever did explain it to either of them.’ And Petrushevskaya is all the more seditious for that.

In ‘The God Poseidon’ the narrator is exploring her friend’s house. ‘I happened to open a wrong door and found myself in a white-marble courtyard where a teacher was leading schoolkids on a field trip.’ These surreal images are scattered throughout the book, leaving the reader dithering between worlds natural and supernatural, real and surreal. It’s a fabulous workout for the imagination. And en route we glimpse Petrushevskaya’s literary humour. Near the start of the story, Nina’s room is described in all its luxury and good taste, ‘–it was simply a dream! I could hardly believe my eyes.’ The author’s exclamation mark tells us she’s having a little joke, I think, particularly since that is indeed what happens.

For Petrushevskaya, the short story is a tragic form. She believes that it must shock so the reader will remember, and she quotes Joyce’s ‘Dubliners’ and Nabokov’s ‘Spring in Fialta’ as examples of this. In fact, ‘The God Poseidon’ has a very strong relationship with ‘Spring in Fialta’. In both stories the narrators meet a friend, both friends are called Nina, both stories are set by the sea, and both stories conclude with a dead Nina. They differ in almost every other way, but this dialogue between works adds another interesting dimension to the short story form – enabling stories to communicate across time and space in the reader’s mind as well as the writer’s.

For Petrushevskaya, the short story is a tragic form. She believes that it must shock so the reader will remember, and she quotes Joyce’s ‘Dubliners’ and Nabokov’s ‘Spring in Fialta’ as examples of this. In fact, ‘The God Poseidon’ has a very strong relationship with ‘Spring in Fialta’. In both stories the narrators meet a friend, both friends are called Nina, both stories are set by the sea, and both stories conclude with a dead Nina. They differ in almost every other way, but this dialogue between works adds another interesting dimension to the short story form – enabling stories to communicate across time and space in the reader’s mind as well as the writer’s.

Another of my favourites is ‘The Fountain House’ in which a man seeks to bring his dead daughter back to life. Perhaps the most shocking element in the story is the father’s passionate despair, insane to the point where he believes his daughter to be alive, as well as his determination in the face of all hopelessness as he sets about bribing doctors to revive her. The story is a complex landscape of hospitals, dreams and of course, the Fountain House itself. The climax occurs when, in a dream, the father takes a sandwich to the girl but when he opens it, he finds inside a human heart:

“Give it to me,” she said ponderously.

She was reaching her hand toward his pocket – her arm was amazingly long all of a sudden – and the father understood that if his daughter ate this sandwich, she would die.

Turning away, he took out the sandwich and quickly ate the raw heart himself. Immediately his mouth filled with blood. He ate the black bread with the blood.

‘The Fountain House’ is one of the Requiem stories. The actual Fountain House is a fabulous museum in St Petersburg. It is described as ‘the first museum dedicated to the generation who tried to preserve their inner world in the totalitarian state.’ It houses the Anna Akhmatova Museum where ‘Garden of Other Opportunities’ was displayed – Petrushevskaya’s exhibition of art, plays, and an installation representing her literature. Anna Akhmatova was a poet (now acclaimed) who chose to stay on in Stalinist Russia in spite of the fact that her husband was shot as a Bolshevik sympathiser and many of her friends fled the country. Her work was condemned and censored by the totalitarian regime. Some poetry was circulated underground, but much was destroyed during the revolution and World War II. Her most famous surviving work is ‘Requiem’, about Stalinist terror.

If we are to place an allegory on ‘The Fountain House’ then perhaps the ‘dead’ daughter is Russia’s suppressed artistic culture and the revived daughter is its rebirth. But at the end of the story, we are left to work out which reality we believe: a mystical experience, a trade with Death, or a mad hallucinatory episode. ‘The Fountain House’ ends, ‘He kept quiet about the raw human heart he’d had to eat. It was in a dream, though, that it happened, and dreams don’t count.’

That makes me laugh because in Petrushevskaya’s world we’re always in a dream; dreams are valuable currency. In reality, without dreams of one kind or another where would we be? And in Soviet Russia, I imagine dreams were the stuff of survival.

Another favourite story of mine is ‘Marilena’s Secret’, one of the Fairy Tales. It begins, ‘There once was a woman so fat, she couldn’t fit in a taxi, and when going into the subway she took up the whole width of the escalator.’

We discover that Marilena is in fact two pretty dancing girls, one blonde and one dark. An evil magician wants to marry the blonde and turn the other into a teakettle. The magician is rich and famous and yet he can’t love anyone and sees evil everywhere. When the girls refuse, he turns them both into Marilena, yet for two hours every night, the girls come out to dance. But this is Marilena’s story, and there’s something really appealing about her dilemma. She’s like those of us writers who spend our day at work or looking after the family and for a few hours at night, in secret, the imagination powers up, our light and dark sides battle it out and the magic takes place. To survive, Marilena joins the circus and picks up the whole front row of the audience to demonstrate her enormous strength. ‘That’s the only way she could make money at the circus. In art you must always shock your audience; otherwise you’ll quickly starve to death.’

Marilena falls for a conman, Vladimir, who takes over her business and of course attempts to rob her and get her into trouble. Eventually, his secretary, Nelly, has plastic surgery and turns herself into a fake Marilena. But a miracle occurs, the girls dance to fame and riches, and Vladimir and the wicked magician send flowers and letters in praise of their great beauty and talent.

Petrushevskaya’s power is in her devastating honesty and truth. She writes about terror, about the disintegration of human values, about insanity and despair. And she writes about fighting back. Perhaps, in ‘Marilena’s Secret’, Vladimir represents the new post-Soviet chaos. Possibly, the magician is the old Soviet state. Maybe Marilena is Petrushevskaya. It’s easy to find an allegory in all this, and that’s fine, but there is also the chance of discovering your own truth. It’s much more rewarding to seek out one’s own metaphor. That’s the joy of the fable, parable and folk tale. You can discover things about yourself, find answers and reassurance, and a reason to go on doing what you’re doing. Because these stories are powered by a relentless, driving optimism in the face of hopelessness and despair. Buy the book. I promise you will devour every word… and then what will happen?