'Firewood' © Mike, 2005

THE WOOD THAT STARTS THE FIRE

by A. J. ASHWORTH

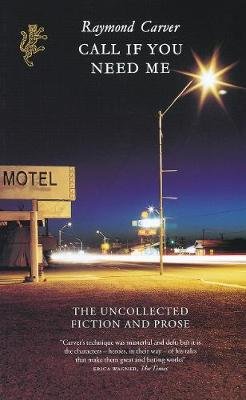

It’s not always obvious why some stories stay with us, why they seep into the small tributaries in our brains, colouring our minds like ink in water. Sometimes the reason a story resonates may be more obvious though. Raymond Carver’s ‘Kindling’, published posthumously in the book Call If You Need Me in 2000, is one that has a more obvious connection for me.

It is the story of Myers, a man who is ‘between lives’ – an alcoholic who has been in a drying-out facility, whose marriage has failed and who has arrived near the ocean to rent a room from a couple called Sol and Bonnie while he tries to sort himself out. It affected me from the first moment I read it. Yes, because of the simplicity and beauty of Carver’s prose, which can be seen in all his stories; and, yes, because of the poignancy of the man’s situation, the small glimpses into his life which are shown to us in a sad and beautiful light. But, more than this, it is because of the sense of hope that comes as we reach the end of the story. A hope that arrives because of one simple act: that of chopping wood.

Once, many years ago, when I was ill with anxiety – unable to eat, not sleeping, even finding the thought of switching on the kettle too much – my then-boyfriend came for me and took me down to his grandparents’ farmhouse in a village on the edge of Bristol. Going there would give me time to myself while his family were away and he was at university. It would give me time in natural surroundings. It would give me time to allow the feelings of edginess and panic that seemed to have come out of nowhere to subside. What it would also give me was an axe and a pile of logs outside the farmhouse that I could go and chop whenever I wanted to. And that was what I did. With the sun on my skin and the hushing sound of the breeze in the trees, I chopped wood in the afternoons, sometimes making a fire to read by, until I started to come back to myself. And in ‘Kindling’, the same thing happens for Myers. A pile of logs is delivered to Sol’s house in readiness for winter and Myers offers to chop them up for him – even though he hasn’t chopped wood before and has to rely on Sol to show him how to use the power saw and the axe. This small act of touching saw blade to wood lasts just a few hours over a couple of days but it helps Myers start to reawaken to himself.

Once, many years ago, when I was ill with anxiety – unable to eat, not sleeping, even finding the thought of switching on the kettle too much – my then-boyfriend came for me and took me down to his grandparents’ farmhouse in a village on the edge of Bristol. Going there would give me time to myself while his family were away and he was at university. It would give me time in natural surroundings. It would give me time to allow the feelings of edginess and panic that seemed to have come out of nowhere to subside. What it would also give me was an axe and a pile of logs outside the farmhouse that I could go and chop whenever I wanted to. And that was what I did. With the sun on my skin and the hushing sound of the breeze in the trees, I chopped wood in the afternoons, sometimes making a fire to read by, until I started to come back to myself. And in ‘Kindling’, the same thing happens for Myers. A pile of logs is delivered to Sol’s house in readiness for winter and Myers offers to chop them up for him – even though he hasn’t chopped wood before and has to rely on Sol to show him how to use the power saw and the axe. This small act of touching saw blade to wood lasts just a few hours over a couple of days but it helps Myers start to reawaken to himself.

For Myers, chopping the wood becomes something he not only wants to do but something that he must do: ‘He decided that he would cut this wood and split it and stack it before sunset, and that it was a matter of life and death that he do so. I must finish this job, he thought, or else.’ And we sense the truth of this. For Myers, who stands in a kind of no man’s land, a limbo between his old, failed life and the possibility of something else, it is as if chopping this wood will give him the symbolic kindling that will help him start the fire of his new life – whatever and wherever that may be.

It may help him in another way too. Throughout the story we’re never told what Myers does for a living – Sol and Bonnie both ask at separate times but never get an answer. Other questions go unanswered too as Myers, a quiet, emotionally bruised man, stays out of their way and keeps to his room. What we are shown though is that Myers has a notebook that he tries but fails to write anything decent in – and from this we assume he is a writer, albeit one who is struggling to produce anything worthwhile. On his first night at Sol and Bonnie’s he writes ‘Emptiness is the beginning of all things’ which he laughs at and declares to be ‘rubbish’. Another time all he can manage is the word ‘Nothing’. In contrast though, words flow easier for Bonnie, who we are told early on in the story wants to be a writer. When we are given glimpses into some of her work, inspired by the new lodger, we can see that even though she can produce in a way Myers can’t at the moment, her words are clichéd, lacking freshness: ‘This tall, stooped—but handsome!—curly headed stranger with sad eyes walked into our house one fateful night in August.’ The difference between the two of them reminds me of the well-known Thomas Mann quote: ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ And indeed for Myers, writing is something that is not coming easily at all.

Stories are about change though, about turning points in people’s lives and, as I said earlier, there is hope for Myers here. Change comes for him after he starts to chop the wood. After cutting up the first batch, the words that have eluded him start to return and he is able to write about the ‘sweet smell’ of the sawdust in his shirtsleeves. He makes no comment on the quality of the words this time and instead they are just allowed to be on the page. By the end of the story, after he has finished chopping all the wood, the words are flowing easier – like the Little Quilcene River that he can hear from his room, flowing into the ocean:

‘Outside my window I can hear a river and in the valley behind the house there is a forest and precipices and mountain peaks covered with snow. Today I saw a wild eagle, and a deer, and I cut and chopped two cords of wood.’

There is no hint of a story here yet, but unlike with Bonnie’s writing, there is beauty, a plain and unfussy description of the natural world and a man’s encounter with it.

These sentences which are some of the last in the story leave me with hope for Myers – hope that he can start anew, that he can make different choices, that he can carve a better life for himself; as Carver eventually did for himself after his own battles with alcoholism.

‘Kindling’ is not only a word for those small pieces of wood that can help to start a fire but is a word related to alcoholism, whereby repeated episodes of withdrawal can lead to more severe symptoms, including seizures. I don’t know if Carver knew this; perhaps he did. But there is no reference to it in the story, no hint that this is what the title means. In fact, the only reference to kindling is when Sol tells Myers not to bother making any when he chops the wood. I like to think that the title doesn’t refer to alcoholic kindling though as it would cast too dark a shadow over the story; it would make Myers’ future seem too bleak – as if he might never escape from the painful merry-go-round of drinking and withdrawing. Instead, for me, there is hope in the title, as there is at the end of the story – the hope that comes from being able to kindle a new life after the death of the old.

‘Kindling’ is not only a word for those small pieces of wood that can help to start a fire but is a word related to alcoholism, whereby repeated episodes of withdrawal can lead to more severe symptoms, including seizures. I don’t know if Carver knew this; perhaps he did. But there is no reference to it in the story, no hint that this is what the title means. In fact, the only reference to kindling is when Sol tells Myers not to bother making any when he chops the wood. I like to think that the title doesn’t refer to alcoholic kindling though as it would cast too dark a shadow over the story; it would make Myers’ future seem too bleak – as if he might never escape from the painful merry-go-round of drinking and withdrawing. Instead, for me, there is hope in the title, as there is at the end of the story – the hope that comes from being able to kindle a new life after the death of the old.

After finishing chopping the wood, Myers tells Sol and Bonnie that he will be leaving soon; in fact, he thinks after, he could pack up and be gone in ten minutes if he wanted to. He doesn’t leave straightaway though but instead gets undressed and turns off the light, opens the window so that he can perhaps better hear the comforting flow of the Little Quilcene River. In the final sentences Carver leaves us feeling that Myers has found some kind of inner peace for himself while he’s been there: ‘He left the window open when he got into bed. It was okay like that.’

Myers is sober, his muscles are aching from the chopping of the wood, and he has the promise of new words flowing like that river he can hear off in the distance. I think he will be alright. At least I hope he will.

~

A. J. Ashworth is the author of the short story collection Somewhere Else, or Even Here, which won Salt Publishing’s Scott Prize, was nominated for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and shortlisted in the Edge Hill Prize. She is also the editor of Red Room: New Short Stories Inspired by the Brontës. She has won funding from Arts Council England, the Society of Authors K. Blundell Trust and, most recently, the Society of Authors Authors’ Foundation. She has previously won the Baltic Writing Residency in Scotland and was a Hawthornden Fellow in 2014.