photo © Kevin Lawver, 201o

~

Gary Budden is editor at Unsung Stories. His work has appeared in Structo, Elsewhere, Unthology, The Lonely Crowd, Gorse, Galley Beggar Press, and many others. He writes regularly for Unofficial Britain and blogs about landscape punk at www.newlexicons.com.

Gary Budden is editor at Unsung Stories. His work has appeared in Structo, Elsewhere, Unthology, The Lonely Crowd, Gorse, Galley Beggar Press, and many others. He writes regularly for Unofficial Britain and blogs about landscape punk at www.newlexicons.com.

~

~

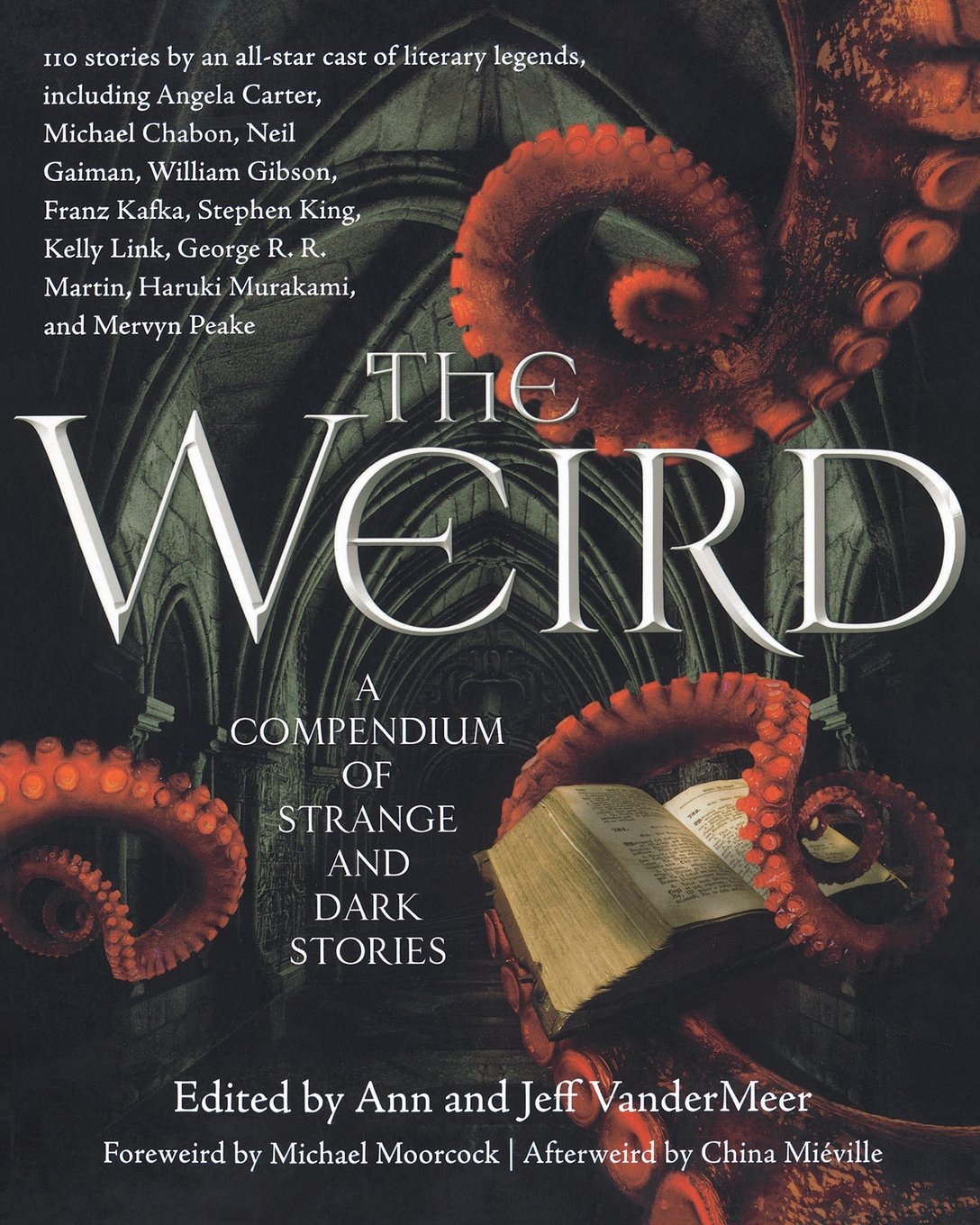

There is one sub-genre particularly well-suited to the short form, that goes under a number of names: the weird tale, the strange story, the New Weird, interstitial fiction, and many more. It’s nebulous enough to include work from M.R. James, China Miéville, Angela Carter, H.P. Lovecraft and Karen Joy Fowler, but coherent enough to still form a recognisable type of writing. It has its roots in Victorian ghost stories and the American pulp magazines of the 1920s and 1930s, most significantly Weird Tales, where writers such as Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard and Lovecraft himself had their stories first printed. This ‘speculative’ brand of fiction has always fallen outside the agreed boundaries of ‘literary fiction’, although these days you can buy Penguin Classics editions of these writers’ work – perspectives clearly change over time as to what is considered worthy of the name ‘literature’.

Whatever people want to call it, it is a persistent sub-genre that exists mainly in the short story and, to a lesser extent, novella forms. It embraces ambiguity and has literary pretensions, yet uses elements of dark fantasy, magic realism, science fiction, body horror, folklore and myth. Sustained weirdness is hard to maintain over the length of an entire novel, but within the confines of a short story much more attention can be paid to mood, atmosphere, a creation of unease and the sense that something is just slightly wrong.

Whatever people want to call it, it is a persistent sub-genre that exists mainly in the short story and, to a lesser extent, novella forms. It embraces ambiguity and has literary pretensions, yet uses elements of dark fantasy, magic realism, science fiction, body horror, folklore and myth. Sustained weirdness is hard to maintain over the length of an entire novel, but within the confines of a short story much more attention can be paid to mood, atmosphere, a creation of unease and the sense that something is just slightly wrong.

The weird tale has roots in the traditional ghost story, making effective use of the classic twist ending, with monstrous details belying its pulp lineage. But drawing from literary fiction, it is also happy with suggestion, ambiguity and the unexplained. It can take turns towards dark absurdity and the all-out bizarre – though not bizarro – as seen in the work of writers like Kelly Link (faery handbags, pyjamas inscribed with the diaries of strange women), Helen Marshall (ghost thumbs, factory line santas and a very sad can of tomato soup) and Michael Cisco (the psychotic lack of logic and reason in ‘The Genius of Assassins’).

One of the key ways the weird tale is different, at least in the United Kingdom, from its more consciously literary cousins is its acceptance as shorter work. It is common for a writer of the weird tale to only ever write short fiction – or for their short fiction to be viewed in equal esteem as their longer works. Two of the genre’s biggest historical names, Lovecraft and M.R. James, never wrote a novel (though it’s worth pointing out Lovecraft died destitute and James’ ghost stories make up a just a fraction of his published work). A writer such as Ramsey Campbell is lauded equally, if not more, for collections like Demons by Daylight and Dark Companions as he is for his novels. A brilliant but uneven writer such as Algernon Blackwood is far more well-known for short works like ‘The Wendigo’ and ‘The Willows’ than his novels, which were often baggy and inconsistent. Clive Barker, rightfully praised for his novels, is still talked about in hushed tones for his horror collection, Books of Blood (in my opinion containing one of the greatest pieces of strange short-fiction ever written: ‘In the Hills, the Cities’, where two rival communities in the former Yugoslavia, Popolac and Podujevo, form towering giants from the lashed-together bodies of their own inhabitants to battle it out in an ancient ritual).

This is not the case with literary fiction in the UK, where a writer’s short-fiction is often seen as a warm-up effort or a stop-gap between longer works. Yet in the world of speculative fiction, the form is celebrated.

There is a bigger question, of course, as to whether there’s a sustainable career in just writing short fiction. Short story collections are notoriously tough to sell in a market geared towards three-book series. So why do people keep writing them? There’s always been a tension in the publishing world between commercial concerns and what people tentatively consider art. The short story is a significant factor in the argument for pursuing writing as an artform in itself – if commercial success was the only imperative then writers  would have given up on short stories long ago and concentrated solely on the novel. But this is clearly not the case – we receive a constant stream of short story submissions for Unsung Shorts. The number of short story journals and websites in the UK alone is very large, within speculative fiction, literary fiction and every other genre. Writers are out there creating weird and wonderful short stories – the question is how to encourage more UK readers into reading it.

would have given up on short stories long ago and concentrated solely on the novel. But this is clearly not the case – we receive a constant stream of short story submissions for Unsung Shorts. The number of short story journals and websites in the UK alone is very large, within speculative fiction, literary fiction and every other genre. Writers are out there creating weird and wonderful short stories – the question is how to encourage more UK readers into reading it.

But, as we’ve said, there is a lot of support and acceptance for the short form in speculative fiction, as evidenced by Undertow Publications’ ongoing Year’s Best Weird Fiction anthology series, mammoth (and essential) anthologies like The Weird, excellent journals and magazines like Interzone, Black Static, The Drabblecast, Three Lobed Burning Eye and Weird Fiction Review. It’s undeniable that many writers in the genre make a name for themselves through their short fiction; some even become famous for it. This isn’t a contemporary resurgence either: delve back in time a bit and you’ll discover the mammoth anthologies compiled by Alberto Manguel, Black Water and White Fire, or Antología de la Literatura Fantástica (The Book of Fantasy) edited by Jorge Luis Borges. Trends wax and wane but there has always been a dedicated following for the weird tale.

This is what we are doing ourselves with Unsung Shorts, celebrating and giving a home to the short speculative story and contributing to that long tradition that stretches back over a century. Recent highlights have included disturbing tales like Josh Sczykutowicz’s ‘What the Light Washed Away’, the surrealistic ‘Book Boy’ by Zack Graham, and Maggie Secara’s ‘Charmed and Strange’, to name but a few. It’s been a joy discovering and encouraging writers working in this field – and we are constantly surprised not only by the quality of the work but the strength of writers’ imaginations.

There are many great examples and studies of the form that we would suggest anyone interested in the short story to go and seek, whether or not you write ‘the weird tale’ or speculative fiction yourself. As a writer, it will help open up new possibilities and potential for what is achievable within the form and, as a reader, well, hopefully you’ll discover some brilliant new writers to love.

Here are some of my favourite stories I consider to be exemplars of the form and genre, hopefully showing just what can be done with the short story when your imagination is let off the leash.

‘The Call of Cthulhu’ by H.P. Lovecraft

No discussion of speculative fiction and short stories can be had without mentioning Lovecraft. His attitudes to people we can deem ‘the other’ (essentially anyone not called H.P. Lovecraft) are now correctly regarded as abhorrent, but it’s hard to deny the impact he has had on the collective imagination – and one could argue that his personal beliefs fuel and give power to the perverse horror in many of his stories. Tales like ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ are foundational texts for weird fiction, and anyone with an interest in it should read them.

‘The White People’ by Arthur Machen

The great Anglo-Welsh mystic created one of the very finest short stories, in the form of ‘The White People’. A young girl’s diary becomes more and more disturbing as hints of witchcraft and black magic creep in… a key foundation for the British folk-horror that followed in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

‘The Neglected Garden’ by Kathe Koja

‘The Neglected Garden’ by Kathe Koja

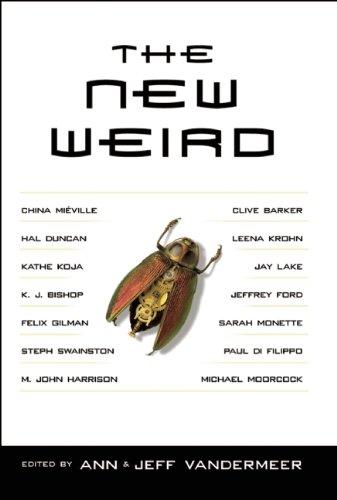

I first encountered this story in The New Weird anthology edited by Ann & Jeff Vandermeer, which also served as my introduction to Thomas Ligotti, Leena Krohn and Clive Barker. This story has stuck with me for a long time, and is one I often return to. It is, if I have to reduce it, a piece of feminist body-horror, examining a failing relationship and a woman who refuses to be discarded by an uncaring misogynist man. A great example of the unsettling power of speculative fiction addressing real social issues through the bizarre and horrific.

‘The Last Feast of Harlequin’ by Thomas Ligotti

The dark prince of the short story, and not one for the faint-hearted. Ligotti is rightly lauded as a master of short prose (as evidenced by his recent Penguin Classics reissue of his first two collections – one of only ten living writers to receive such an honour), taking the cosmic horror and general misanthropy of Lovecraft, upping the ante on the nihilism and with an infinitely more sophisticated writing style. A novel-length work like this would probably drive you insane, much like Ligotti’s unnamed narrators, but these concentrated blasts of darkness work perfectly in short fiction. ‘The Last Feast of Harlequin’ acts as a good introduction to Ligotti, with its arcane backwoods American rituals, the recurring obsession with clowns, harlequins and jesters, the feeling of doom hanging over everything and all-out horrifying weirdness as the denouement. You might not look at earthworms the same way ever again.

‘Wild Acre’ by Nathan Ballingrud

One of my favourite short stories in this or any other genre by one of my favourite writers. If a horror element was added to the work of Raymond Carver, you’d end up with work like Ballingrud’s – resolutely American blue-collar, with the emphasis very much on characters and their real human lives, where the speculative elements are almost incidental. This story is the best of the bunch in my opinion; whether the atrocity the narrator witnesses really was the actions of a lycanthrope, it doesn’t matter – it ruins his life. Devastating in a way only fiction can achieve.

‘The Hide’ by Liz Williams

As a lover of bird watching, cosmic horror and the uncanny power of the British landscape, this short story is an all time favourite of mine. A reminder that Britain is an ancient country crowded with ghosts and powers we may never understand. I read ‘The Hide’ and became transfixed with the image of white cormorants flying over the marshes of where I grew up, and what that might mean. A brilliant example of how the weird tale can transform mundane, everyday situations into ones of awe, terror and wonder.

‘Deus Ex Arca’ by Desirina Boskovich

This is an excellent example of how the weird has evolved. At once absurdist, comedic, tragic and utterly terrifying it sits outside of genre classification. A prodigious twist on Pandora’s Box, it works on various levels, the most obvious being a bewildering account of a boy uncovering a great conspiracy. But as you unpack it, it becomes about life, the potential for creation and loss, the magic of childhood and the terrible realities of adulthood. Boskovich’s deft use of a simple metaphor, and her free approach to genre is firmly steeped in the weird. The unknowable, the sense that our reality is just a consensus or illusion, is the cornerstone of a superbly complex piece.