photo by Mike Lee

Dan Powell recommends the graphic short stories of Yoshihiro Tatsumi, in an essay named as one of two runners-up in the 2014 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition.

*

Comments from the judging panel:

‘A highly engaging essay, providing an interesting and intelligent overview of Tatsumi’s dark and sometimes disturbing stories’; ‘Clearly very well researched’; ‘a refreshing and interesting approach to the brief’; ‘I hope this will go some way to introducing new readers to Tatsumi’s work’.

*

by Dan Powell

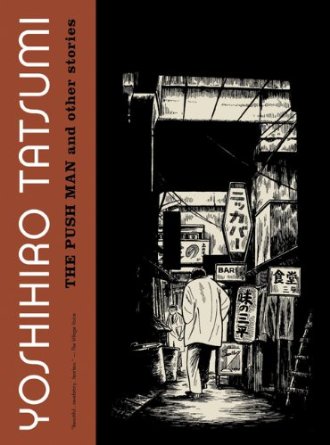

The stories in Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s collection The Push Man and Other Stories trouble me. Each time I return to my well worn Drawn and Quarterly edition, I am struck by their undiminished capacity to unnerve.

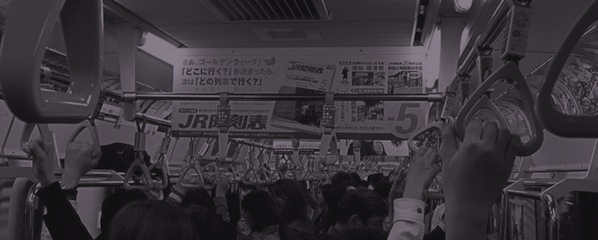

Set against a backdrop of low rent city streets, crowded subways, and claustrophobic apartments, many of these stories are littered with acts of brutality and violence, some of a sexual nature. Yet the adult themes and images in this manga collection are not intended to titillate or satisfy some prurient desire in the reader, as psychiatrist Dr Frederick Wertham might have argued. Instead, as The San Francisco Examiner described on publication of the collection, the stories are ‘an unflinchingly honest exposé on the private lives of ordinary, working class men living in the hustle and bustle of Japan’s thriving metropolis’.

Set against a backdrop of low rent city streets, crowded subways, and claustrophobic apartments, many of these stories are littered with acts of brutality and violence, some of a sexual nature. Yet the adult themes and images in this manga collection are not intended to titillate or satisfy some prurient desire in the reader, as psychiatrist Dr Frederick Wertham might have argued. Instead, as The San Francisco Examiner described on publication of the collection, the stories are ‘an unflinchingly honest exposé on the private lives of ordinary, working class men living in the hustle and bustle of Japan’s thriving metropolis’.

In 1969, when these stories were individually published in the pages of bi-weekly magazines, Tatsumi felt it necessary to differentiate his new adult-oriented style of stories from other more traditional manga of the period. Gekiga, the Japanese for dramatic pictures, describes a gritty, naturalistic style of cartooning that deals with mature themes, characters and situations. From the opening act of the first story, ‘Piranha’, in which a factory machinist rips his own arm off at the elbow in a machine press so he can claim compensation, it is clear that the strips included in The Push Man and Other Stories are not intended for kids.

Tatsumi uses adult themes and graphic imagery to examine the lives of his characters with a raw, emotional honesty. In a 2004 interview included at the end of The Push Man and Other Stories, Tatsumi describes the motivation behind his early Gekiga strips: ‘I took an interest in the working class who lived around me. I wanted to provide slice-of-life portraits in my manga.’

Tatsumi’s ability to disturb his readers grows from his unflinching focus on the lives of working class men. His protagonists include a porn film projectionist horribly desensitised by his repeated exposure to graphic sexual imagery; a sperm donor who stalks the recipient of his donations; a man who works all day disinfecting office spaces and then becomes obsessed with disinfecting prostitutes; a sanitation worker who dumps the aborted foetus of his own child in a sewer; and, most disturbingly, a seemingly mild mannered office worker who, on discovering a sex slave hidden in a work colleague’s home, steals the woman for himself rather than free her. It is not surprising that, at the end of the interview which closes the collection, Tatsumi asks that readers: ‘do not interpret these stories as representative of the author’s personality.’ However, his wish to distance himself from his troubled male protagonists does not stop him displaying sympathy for them.

In the title story, ‘The Push Man’, a young rail worker pushes crowds of passengers onto the over-capacity trains at rush hour, yet his isolation is apparent. The physical contact required by his job can all too easily become inappropriate, but the Push Man is professional in his conduct. A colleague jokes about shoving the ass of ‘some hot chick’ but the Push Man refuses to join in. When he returns home to study for entrance exams, his thoughts remain filled with the cries of those he has shoved into cramped train carriages during his day’s work.

The next day, a woman’s clothes are torn in the crush to get on a train and it is the Push Man who comes to her aid, giving her the jacket of his uniform. They go out for a drink and end up spending the night together. The following day he returns to his bedsit to find her and two other women waiting for him. They jump him and shove him down and, despite his protests, tear off his clothes.

The next day, a woman’s clothes are torn in the crush to get on a train and it is the Push Man who comes to her aid, giving her the jacket of his uniform. They go out for a drink and end up spending the night together. The following day he returns to his bedsit to find her and two other women waiting for him. They jump him and shove him down and, despite his protests, tear off his clothes.

Abruptly the scene cuts to him in uniform, on the platform, swamped by the fast moving crowd. He yells to be let out, but no one hears. The reader is left unsure which of these events are real and which are representations of the character’s fantasies. The only certainty here is the vast sense of isolation the character feels and, as a train moves away from the platform in the story’s final panel, it is an isolation that the reader shares.

Tatsumi wants his readers to empathise, to sympathise, to relate closely with his characters. He waits for them to do just that and then he shows what these men are capable of and, by extension, what any man might be capable of. In ‘The Push Man’, in ‘Projectionist’, in ‘Disinfection’, in ‘Telescope’ and in ‘Make-up’, all stories in which the main protagonist’s isolation is vast, this feeling of empathy is uncomplicated. Though these men might hurt themselves through their actions, they do not purposefully harm anyone else. In these stories, the reader can be complicit without feeling compromised, but in others this identification is used to shake the reader to the core.

Tatsumi’s repeated use of the same models for various male characters across the many stories in this volume is not evidence of a sloppy visual style, nor is it an accident that his male characters are often mute. Their uniformity of appearance and lack of voice works to exaggerate their isolation and disassociation from those around them, while at the same time this visual repetition presents each individual character as successive aspects of a universal everyman. This careful interrelation of script and artwork makes it inevitable that a male reader will slip through the fourth wall and more readily sympathise with and even inhabit the space held by central character. It is this aspect of Tatsumi’s work that most disturbs me.

In ‘Piranha’, I am made to feel a deep sympathy for the protagonist who cuts off his own arm to claim compensation and gift his wife the funds she needs to open up her own bar. This sympathy only deepens when his wife becomes distant and uninterested in sex and the machinist discovers she is engaged in a sexual relationship with another man. I feel this deep sympathy until, in revenge, he shoves his wife’s arm into a piranha tank and holds it there as the fish maim her. This act, while understandable in terms of character motivation, is inexcusable and its unsettling nature is magnified because of how close Tatsumi makes reader and character.

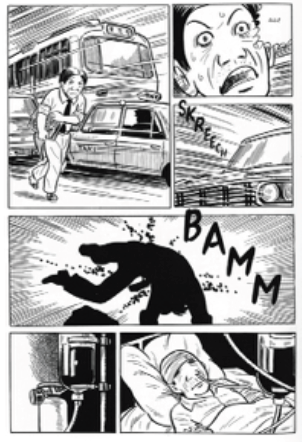

Tatsumi stretches sympathy and complicity to its limits over and over throughout the collection. In ‘Black Smoke’, I feel for the cuckolded incinerator attendant, until he allows his wife to burn to death in their home. In ‘Traffic Accident’, I empathise with the loneliness of the car mechanic obsessed with a TV porn channel hostess, especially when she comes into his garage and in his awkwardness he degrades himself. I even sympathise with his final act of suicide, until the story reveals that he tampered with the brakes of the hostess’ car, also causing her death. In ‘The Burden’, the main character’s opening act of kindness – buying a bowl of noodles for an ill homeless woman – lulls the reader into a false sense of sympathy that is immediately and repeatedly shattered, first by the man taking advantage of her sexually, then by the discovery that he is a married man, and finally by his murderous response to anxieties about becoming a father.

In ‘Bedridden’, easily the darkest tale of the collection, a middle-aged clerk in a medical insurance office is hit by a car and must ask a young colleague to go to his apartment and feed the young woman he has been ‘taking care of’. Once there, the young man discovers a sex slave who has been shaped to satisfy the pleasures of the man she serves: her feet have been bound in the ancient Chinese manner, her tongue and vagina have been made to develop abnormally, and her skin has been made smooth and silky through a strict vegetarian diet.

In ‘Bedridden’, easily the darkest tale of the collection, a middle-aged clerk in a medical insurance office is hit by a car and must ask a young colleague to go to his apartment and feed the young woman he has been ‘taking care of’. Once there, the young man discovers a sex slave who has been shaped to satisfy the pleasures of the man she serves: her feet have been bound in the ancient Chinese manner, her tongue and vagina have been made to develop abnormally, and her skin has been made smooth and silky through a strict vegetarian diet.

Tatsumi does not reveal the young woman in the artwork, but keeps her hidden under blankets instead. The shock that plays across the young man’s face as he looks in at the woman mirrors that which the reader feels when she is described by the still hospitalised older man. This shared emotion between reader and character creates an expectation, in that the young man will help the girl in someway, by calling the police or involving some sort of social service, perhaps. It is an expectation that makes his final act of stealing the young woman for himself all the more disturbing.

No wonder then, as a male reader, that I find these stories troubling. It is not just the acts themselves that generate this response, but also the ease with which these men are able to execute them. Tatsumi’s style involves rapid jump cuts from scene to scene, with the reader forced to fill in the gaps between the panels. The rapidity with which characters perform some dark, unforgivable action means there is little time in which to disengage the sympathy previously felt for the protagonist. The reader is right alongside as the character’s darkest thoughts are acted out. In the closing panels of each story, Tatsumi does not judge his characters, but instead leaves the reader to draw their own conclusions and make their own judgements about what has taken place.

The disquieting nature of Tatsumi’s work is further enhanced by his negative depiction of women in the earliest of the stories presented in the collection. As with the male main protagonist model, he often reuses the same visual model for many different female characters. Most notably, he uses the same design for a number of the wives in the collection, and each time this model is used, this particular image of a woman seems to represent the cliché of the unfaithful, greedy and nagging wife. In later stories – most notably ‘The Push Man’, ‘Make-up’ and ‘My Hitler’ – this less nuanced depiction of women is replaced with a more complex and sympathetic one in which the female characters are confident, caring individuals who prove themselves more capable than the men that surround them.

The disquieting nature of Tatsumi’s work is further enhanced by his negative depiction of women in the earliest of the stories presented in the collection. As with the male main protagonist model, he often reuses the same visual model for many different female characters. Most notably, he uses the same design for a number of the wives in the collection, and each time this model is used, this particular image of a woman seems to represent the cliché of the unfaithful, greedy and nagging wife. In later stories – most notably ‘The Push Man’, ‘Make-up’ and ‘My Hitler’ – this less nuanced depiction of women is replaced with a more complex and sympathetic one in which the female characters are confident, caring individuals who prove themselves more capable than the men that surround them.

This growing complexity is further evidenced in the development of Tatsumi’s visual style. As the collection progresses, the backgrounds become more realistic; the level of detail in the litter strewn city streets and cramped apartments that provide the backdrop for these stories increases in parallel with Tatsumi’s confidence in his own emerging oeuvre.

Meanwhile, his main characters grow more stylised, more cartoonish, an artistic choice that makes these figures stand out against the verisimilitude of their setting. These are men out of sync with the world they inhabit. This contrast serves to reinforce the idea of Tatsumi’s main characters as representing an everyman, while their visual disassociation with the world they are inhabiting subtly foreshadows the isolations and separations that motivate their violent and disturbing actions.

In Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag asserts that ‘real art has the capacity to make us nervous’. I fear that my attempt to explain the disquiet I feel when reading this challenging and confrontational collection may have reduced the work to its content, but that is not to say, as Sontag goes on to argue, that in doing so I have tamed the work of art. Re-opening the covers of The Push Man and Other Stories I feel the same disquiet move through me as on my first reading. There is nothing manageable or conformist about Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s style of graphic storytelling. These are stories designed to make the reader nervous. These are works of art.

~

Yoshihiro Tatsumi is widely held as the ‘grandfather’ of Japanese alternative comics. Born in 1935, in Tennoji-ku, Osaka, he received the Japanese Cartoonists’ Association Award in 1972, has received multiple Eisner awards and, in 2009, was awarded the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for his autobiography in graphic novel form, A Drifting Life.

~

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in the pages of Carve, Paraxis, Fleeting and The Best British Short Stories 2012. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the 2013 Scott Prize and is published by Salt. He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in the pages of Carve, Paraxis, Fleeting and The Best British Short Stories 2012. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the 2013 Scott Prize and is published by Salt. He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

One thought on “The Unnerving Tales of Yoshihiro Tatsumi”

Comments are closed.