photo © Patrizio Martorana

by Julia Anderson

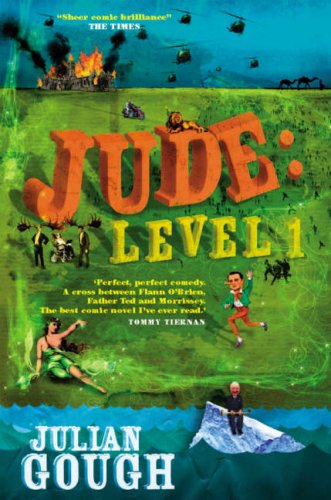

As I read the first sentence of ‘The Orphan and the Mob‘, my eyes widened. At only sixteen words long, Julian Gough managed to insert into his first sentence: urination, a mob, and an orphanage burning down. Kudos to him. I’d be hard pressed to fit these into an entire short story, let alone one sentence:

If I had urinated immediately after breakfast, the mob would never have burnt down the orphanage.

I was in for a treat.

The orphan is Jude and, after he eats breakfast in the dining hall at the Tipperary orphanage, he needs to visit the toilet. On his way, he hears the letterbox clatter and spots a single white envelope on the doormat. Jude is surprised the letter is addressed to him, especially ‘On this day, of all significant days!’ – his eighteenth birthday.

Jude, who has never received a letter before, wants to savour opening it, but, first, he has a dilemma to solve:

I could feel the orphanage coffee burning relentlessly through my small dark passages. Should I open the letter before, or after, urinating? I wished to open it immediately. Yet a full bladder distorts judgement.

Brother Madrigal snatches the letter from Jude, stuffs it up the sleeves of his cassock, and tells him he can read it later that evening. He instructs Jude to hurry off and round up the Honour Guard boys, thus freeing Jude from his quandary about whether to read the letter or urinate first, because, now, he isn’t allowed to do either. Instead, he must lead the Honour Guard  several miles across the countryside to Nobber Nolan’s Bog – a famous and revered boghole – to a crowd of fifty thousand farmers waiting to hear politicians make grand speeches on a huge stage. As they set off, Jude calls for Agamemnon – ‘My dearest companion and the orphanage pet […] a dog of such enormous size’ – to join them on their journey.

several miles across the countryside to Nobber Nolan’s Bog – a famous and revered boghole – to a crowd of fifty thousand farmers waiting to hear politicians make grand speeches on a huge stage. As they set off, Jude calls for Agamemnon – ‘My dearest companion and the orphanage pet […] a dog of such enormous size’ – to join them on their journey.

And what a journey Gough and Jude take us on in this high-comedy Irish tale. The urination question gathers urgency, rising to a disastrous crescendo, and Gough puts all manner of obstacles in Jude’s way to thwart him opening his letter and finding out the secret of his birth.

For Gough, part of storytelling is joke telling. After entering the town, coming out the other side, walking until they run out of road and following a track until they run out of track, Jude and the Honour Guard boys finally arrive at the bog: ‘We hopped over a fence, crossed a field, waded a dyke, cut through a ditch, traversed scrub land, forded a river and entered Nobber Nolan’s bog.’ Jude and the boys make their way through the crowd of farmers towards the stage:

They parted politely, many raising their hats, and seemed in high good humour. “Tis better than the Radio Head concert at Punchestown,” said a sophisticated farmer from Cloughjordan, pulling on a shop-bought cigarette.

Once on stage, Jude counts the orphans and finds they have ‘lost only the one, which was good going over such a quantity of rough ground.’ The humour continues as Teddy “Noddy” Nolan, the spokesperson for Tipperary, addresses the crowd:

“In this place Eamonn DeValera,” everybody removed their hats. “Hid heroically from the Entire British Army.” Everybody scowled and put their hats back on. “During the War of Independence, DeValera,” everybody removed their hats again, “had his Vision.”

Teddy Nolan continues, and the crowd continues to put on and remove their hats when the English are mentioned.

It’s the mixture of humorous and more weighted moments, such as the contents of the letter, that make ‘The Orphan and the Mob’ such a fantastic read. The lighthearted narrative here sets the tone for the story and softens the murder, mayhem and misfortune that are rife at the end, making them darkly comic.

The character of Jude has two obvious motives that drive this story forward. The first is the need to urinate and the second is a yearning to read his letter, which he hopes will inform him about his identity. It’s these dynamics that propel the action and fuel the tension. Whilst listening to the speeches at Nobber Nolan’s Bog, Jude has a realisation:

Neglecting to empty my bladder after breakfast had been an error the awful significance of which I only now began to grasp. A good Fianna Fáil Ministerial speech to a loyal audience could go on for up to five hours.

Furthermore, he knows that standing up and walking off the stage during the speech would be viewed as ‘tantamount to treason’, and would earn him a series of beatings. The only alternative he can see is to relieve himself into his breeches. But, try as he might, Jude cannot manage to ‘unleash the torrent within the line of sight of fifty thousand farmers’.

Struck by sudden inspiration, Jude realises he could step unnoticed behind the velvet curtain when the next ‘Magnificent gust of national rhetoric lifted every hat aloft again’. And when this happens, Jude shuffles along the back wall of the stage, safely hidden behind the emerald curtain, where he finds ‘a magnificent circular long-drop toilet of the type employed in the orphanage’. While Jude relieves himself, he hears Brünhilde DeValera’s mighty voice announcing: ‘“I hereby… officially… reopen… Dev’s Hole!”’ The great curtain parts and reveals Jude urinating into Dev’s Hole. With horror, Jude realises that this toilet is ‘the very source of the sacred spring of Irish nationalism: the headwater, the holy well, the font of our nation’.

The mob of farmers pursue Jude all the way back to the orphanage. Jude seeks safety inside, where he speaks with Brother Thomand, who says to Jude that he will tell him the secret of his birth. But he falls asleep mid-sentence, even though rowdy farmers are outside shouting that they want to kill Jude.

The mob of farmers pursue Jude all the way back to the orphanage. Jude seeks safety inside, where he speaks with Brother Thomand, who says to Jude that he will tell him the secret of his birth. But he falls asleep mid-sentence, even though rowdy farmers are outside shouting that they want to kill Jude.

As Brother Thomand awakes with a start, he says: ‘“I think there was a knock.”’ He goes to the door, but as he reaches it, it bursts open ‘with extraordinary violence, sweeping old Brother Thomond aside with a crackling of many bones in assorted sizes’. Thrown backwards against the wall, he impales the back of his head on a coathook. ‘Though he continued to speak, the rattle of his last breath rendered the secret unintelligible. The Mob poured in.’

Jude runs off into the dark of the long corridor. He finds Brother Madrigal in his office in the south tower and asks him for his letter. ‘Brother Madrigal turned from his desk toward the confiscation safe, then paused by the open window. “‘Who are those strange men on the lawn, waving blazing torches?’” Before long, the letter itself will be smouldering in Brother Madrigal’s left hand. Only three words will be visible…

A spoiler alert will be needed if any more of the plot is revealed. Instead, I’ll leave the story near its ending with the mob and the orphanage boys in a mêlée, and with Jude trying to find a way to escape the collapsing orphanage.

With ‘The Orphan and the Mob’, Gough offers a highly amusing, and dark but not dour short story. It’s a story that delights. It’s a story that, in line after line, fires on all syllables.

~

You can read ‘The Orphan and the Mob’ on Julian Gough’s website.