photo © Adriano Ferreira, 2014

by Mike Smith

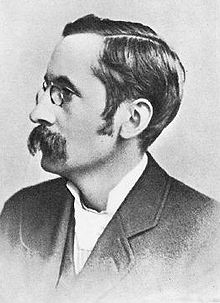

Arthur Morrison, writer of that unremittingly bleak collection of short stories entitled Tales of Mean Streets, has pulled off something rather remarkable with the story ‘Charlwood with a Number’, collected in v.IX The Masterpiece Library of Short Stories.

This story, neither mean nor streetly, is told with a gentle humour and in a mellow, rather than a harsh or strident voice. Even the opening sentence has a softer tone than any of the stories in Mean Streets: ‘Mr Robert Charlwood’s house was the curiosity of the neighbourhood.’

The house, ‘standing in ground of its own’ on ‘the hill of a high London suburb’ is that of a ‘well to do’ amateur astronomer. Morrison has not forgotten his agendas, mind you, for he gently satirises Charlwood’s relative wealth, and the pretensions in which that wealth enables him to indulge. ‘He wrote and printed a great many capital letters after his name.’ Not the badges of an academic excellence, these are the letters of societies he has joined, societies that ‘strictly’ limit their memberships to ‘any gentleman who would pay the subscription.’ Morrison rather enjoys himself, I suspect, with this interlude, for it extends over ten lines of what is only slightly over a five-page story. It ends:

…and I believe Mr.Charlwood’s letters of honour averaged out at fourteen and ninepence apiece, taking one with another; a far more respectable price, though not at all expensive.

It’s worth turning aside here, from what the story is about, to how it is written. The section dealt with above reveals Morrison nudging his narrator into our consciousness, subtly turning a third person narrative into a first person one. He does this only twice during the whole story: during the ‘letters’ sequence and again during the last three paragraphs. The effect of this is to bring the narrator closer to us, to make him, or her, an individual telling us a story, rather than the disembodied voice of unquestionable truth. It emphasises the humanity of the teller, and of the told story, rather than its veracity.

It’s worth turning aside here, from what the story is about, to how it is written. The section dealt with above reveals Morrison nudging his narrator into our consciousness, subtly turning a third person narrative into a first person one. He does this only twice during the whole story: during the ‘letters’ sequence and again during the last three paragraphs. The effect of this is to bring the narrator closer to us, to make him, or her, an individual telling us a story, rather than the disembodied voice of unquestionable truth. It emphasises the humanity of the teller, and of the told story, rather than its veracity.

In fact, Morrison’s comic tale has a great deal to do with humanity, for his protagonist has, on one level, little of it. He has devoted his life to his astronomy, adding an observatory to his house. Presumably on what was called then ‘a private income’, he does not go out to work, but spends his days failing to make a name for himself in his chosen field. Morrison, again gently, satirises this:

He was the author of many contributions to the chief scientific journals. Their inability to print which-for reasons they carelessly left unexplained-caused great regret to the editors…

He has mistaken the sparks from a fire in the kitchen chimney for ‘an extraordinary ascending flight of meteors’. But it’s not all that surprising – early on in the story, Morrison primed us for Charlwood’s incompetence: ‘I have heard it more than hinted, indeed, that he was not a great astronomer at all.’

But Charlwood is content, and settled, as settled in his routines as are the planets and stars that he observes. Much is made of this by the author, drawing on orbits and trajectories, comets and eclipses for his metaphors and imagery throughout the piece. This domestic solar system is wholly dependent on the housekeeper, Mrs Page, whose life is about to be knocked out of orbit, by the deteriorating health of her elderly mother. The knock-on effect of this – the wrong soap in the bathroom, no matches on the mantelpiece, the lunchtime claret cold, the dinner time claret parboiled – throws Mr Charlwood’s universe into chaos. It is a chaos of such a banal scale, compared to the chaos in which those denizens of the Mean Streets existed, but in proportion to the life of Morrison’s protagonist.

And here’s where the humanity rears its compassionate, or pragmatic head, for Charlwood, in order to restore the clockwork order of his household, to set his own universe to rights, demands that Mrs Page bring her mother to stay, and he employs a nurse to look after her too. The balance between pragmatism and actual compassion is fragile, Morrison only hinting at the latter beneath a heavy veneer of the former.

Having had the mother’s situation explained to him, Charlwood’s response might take us by surprise: “Have you considered, Mrs Page,” he said, “what– ah– extreme difficulty and inconvenience… your absence would cause to the– to me?”

Having had the mother’s situation explained to him, Charlwood’s response might take us by surprise: “Have you considered, Mrs Page,” he said, “what– ah– extreme difficulty and inconvenience… your absence would cause to the– to me?”

But, later, as he sits on the stairs, outside the poor room in which the dying mother is presently housed, there is a hint, no more, of something more empathetic: ‘…through all he was oppressed by the memory of that grey-white face, with the trembling eyelids, that lay in the little room behind him.’

The mother is transferred to Charlwood’s house, and, after an initial disturbance – ‘every orbit was irregular’ – calm descends. Seeking ‘refuge from the turmoil’ he, of course, goes to his observatory, where he spots a new star. He’s not the only one to spot it, but he gets his notification in first and, bringing the title to life, the star is given his name: ‘It was strictly called Charlwood with a number which I cannot tell you, being no astronomer.’

Morrison’s ending is not with the restoration of calm. It goes beyond that. Mrs. Page’s mother dies, and so does Charlwood: ‘I believe even Mr Charlwood himself has been dead some time.’ But something has changed. Charlwood’s ‘star twinkles steadily in the place where it first added its tiny light to the sparkling sky.’

Morrison’s seemingly simple ending may not be as trite and unambitious as it might appear at a cursory reading. In fact, it could be seen as an ending as powerful and provocative as any in Mean Streets, asserting the value of the least show of goodness in a human life. Would I be too fanciful to suggest that, in these closing words, the ‘tiny light’ is the compassion of Charlwood, and the ‘sparkling sky’ is the firmament of humanity?

~

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions (Unbound Press, 2010), the novella A Penny Spitfire (Pewter Rose 2011), and, in 2012, Talking To Owls (Pewter Rose), a collection of short stories, monologues and flash fictions. In 2009, he received the degree of MLitt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator. He is keen on the ‘told’ story, and some of his tellings can be found at BHDandMe on Vimeo. He has a collection of essays on short story form due out from Pewter Rose Press, and a collection of short stories from Sentinel Publications. He is a founder/presenter of LitCaff, a monthly evening of fiction (with added poetry) in Carlisle, England. His most recent collection of short stories is The Man Who Found A Barrel Full of Beer, written as Brindley Hallam Dennis. His collection of essays on A. E. Coppard, English of the English, features responses to the tales of A. E. Coppard.

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions (Unbound Press, 2010), the novella A Penny Spitfire (Pewter Rose 2011), and, in 2012, Talking To Owls (Pewter Rose), a collection of short stories, monologues and flash fictions. In 2009, he received the degree of MLitt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator. He is keen on the ‘told’ story, and some of his tellings can be found at BHDandMe on Vimeo. He has a collection of essays on short story form due out from Pewter Rose Press, and a collection of short stories from Sentinel Publications. He is a founder/presenter of LitCaff, a monthly evening of fiction (with added poetry) in Carlisle, England. His most recent collection of short stories is The Man Who Found A Barrel Full of Beer, written as Brindley Hallam Dennis. His collection of essays on A. E. Coppard, English of the English, features responses to the tales of A. E. Coppard.