('Reading' © Jens Schott Knudsen, 2010)

*

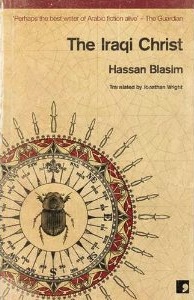

THE IRAQI CHRIST: THE HORROR OF THE PAST

AND THE TERROR OF THE PRESENT

by DR. WALEED AL-BAZOON

*

Iraqi writer Hassan Blasim’s The Iraqi Christ (Comma Press, 2013) is a seismic, ground-breaking short story collection that leaves in its reader’s mind — long after the final page — powerful after-shocks. In the title story, ‘The Iraqi Christ’, Blasim explores, with devastating force, the consequences of two different wars upon his country: the 1990 Kuwait-Iraq war and the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the U.S. and Britain.

The story opens with the Iraqi army soldiers camping in a girls’ school during the 1990 Gulf War. Daniel, the story’s protagonist, soon draws the attention of the other soldiers in his unit. He is a member of the vulnerable Christian minority in Iraq. Also, notably, as a young army recruit, Daniel had once an ambition to be a soldier in the radar unit, but his dream was thwarted by his father’s history as a communist leader in the 1970s. Yet, somehow, strangely, he comes to be known as ‘the radar’ of the unit. If the unit is being targeted by the enemy, Daniel feels an early sense of the threat and moves from the place under attack. Soldiers in the unit stay close to him. Mysteriously, men are saved, and in time, Daniel becomes the most ‘crucial’ soldier in the unit. He saves his comrades many times with his uncanny ability to perceive danger before it hits. In recognition of both his constant gum-chewing and the seeming ‘radar miracles’ he performs, he is dubbed by his comrades, ‘Christ: Chewing Man’.

The story opens with the Iraqi army soldiers camping in a girls’ school during the 1990 Gulf War. Daniel, the story’s protagonist, soon draws the attention of the other soldiers in his unit. He is a member of the vulnerable Christian minority in Iraq. Also, notably, as a young army recruit, Daniel had once an ambition to be a soldier in the radar unit, but his dream was thwarted by his father’s history as a communist leader in the 1970s. Yet, somehow, strangely, he comes to be known as ‘the radar’ of the unit. If the unit is being targeted by the enemy, Daniel feels an early sense of the threat and moves from the place under attack. Soldiers in the unit stay close to him. Mysteriously, men are saved, and in time, Daniel becomes the most ‘crucial’ soldier in the unit. He saves his comrades many times with his uncanny ability to perceive danger before it hits. In recognition of both his constant gum-chewing and the seeming ‘radar miracles’ he performs, he is dubbed by his comrades, ‘Christ: Chewing Man’.

We move in time to 2003. After the fall of Saddam, Daniel is visited by the unnamed narrator of the story, who is also Daniel’s best friend. The narrator talks to Daniel about returning to the new Iraqi army, but Daniel refuses to join because that army is under the control of the Americans. The narrator joins up while Daniel cares for his elderly mother, who has lost her sight, hearing and memory. Daniel’s sisters and many of his Christian relatives have fled to Canada in flight from, as the narrator notes, ‘the wars and the madness of the religious extremism’. He and his mother battle on, alone. For Daniel, Christian or not, his home is Iraq.

One day, he brings his mother to a restaurant to enjoy a well cooked meal. A handsome and stout young man in his twenties asks Daniel’s permission to sit with them. The young man appears distracted; he looks this way, then that way. He eats and cries at the same time. Daniel asks if he needs help. Suddenly, the young man’s expression changes. He shows Daniel an explosive belt under his jacket. He tells Daniel that if he says anything, he will detonate himself in the restaurant.

As we know, the soldier-narrator is a friend of Daniel’s and, as the story unfolds, he reappears in his own right once more. He describes to us the experience of sharing a patrol with American forces, when all of a sudden, the patrol is targeted by gunfire from one of the nearby houses. The Americans mistakenly conclude that the Iraqi unit targeted them, and they open fire on the narrator and his fellow soldiers. He takes three bullets to the head.

Time moves again and, in a move that is a hallmark of Blasim’s short fiction style, we leap from the traumas of the real to the freedom of the surreal. We find ourselves as readers in the afterlife of the narrator where to his delight he meets his old friend Daniel, the Iraqi Christ. In this new world, the Iraqi Christ tells the narrator that he was captured by the young man in the restaurant, who asked him to go with him to the restaurant toilet, where he gave him an impossible choice: to die helplessly with the others in the restaurant or to put on the belt himself, detonate it and, in doing so, win his mother’s life. The young man explains to Daniel that, if he wears the belt, he himself will take Daniel’s mother out of the restaurant to a place of safety before the explosion. Daniel accepts and blows himself up inside the restaurant.

Time moves again and, in a move that is a hallmark of Blasim’s short fiction style, we leap from the traumas of the real to the freedom of the surreal. We find ourselves as readers in the afterlife of the narrator where to his delight he meets his old friend Daniel, the Iraqi Christ. In this new world, the Iraqi Christ tells the narrator that he was captured by the young man in the restaurant, who asked him to go with him to the restaurant toilet, where he gave him an impossible choice: to die helplessly with the others in the restaurant or to put on the belt himself, detonate it and, in doing so, win his mother’s life. The young man explains to Daniel that, if he wears the belt, he himself will take Daniel’s mother out of the restaurant to a place of safety before the explosion. Daniel accepts and blows himself up inside the restaurant.

As an Iraqi, I find the story compelling. Not only does Blasim explore vital episodes in the recent history of Iraq, but even more importantly, he exposes the reality of our daily lives in which soldiers and civilians — men at the front, minority Christians and even elderly women — become shockingly intimate with the surrealism of violence and terror. Feelings of dread and insecurity are now a part of the identity of the Iraqi people, a people who suffered under the missiles of the Americans in the 1990 Gulf War and who now live under the shackles of terrorists and militia forces in this post-occupation period. Our lives have been narrowed to the meagre square footage of cement bomb shelters.

In this collection, Blasim confronts the terror, trauma and surrealism of unending war in which daily life is itself deformed and mutilated. Whether he is exposing the chaos of life under the despotism of Saddam or life, thirteen years after him, lived at the mercy of competing terrorist groups, Blasim recreates on the page, with all the intensity of the short fiction form, the existence of a country in which its citizens seem always to walk at the edge of an abyss. Yet if there is ongoing horror in the work of Blasim – and there is – there is also a moving sense of our shared humanity in the unexpected moment in which Daniel sacrifices his own life to save his mother.

~

Dr. Waleed Al-Bazoon completed his PhD in English Literature at the University of Chichester in 2013. He is from Basra, Iraq, and until 2003, was a lecturer in literature at the University of Basra. He now lives in the UK and is undertaking post-doc research in the field of contemporary Iraqi fiction. If you share this area of interest or expertise, please feel free to contact Dr. Al Bazoon at email: W.Albazoon@chi.ac.uk.

~

You can find an interview with Hassan Blasim,

author of ‘The Iraqi Christ’, on THRESHOLDS here.