('The Road to Darkness' © Samuel Persson, 2017)

THE DARKNESS WITHIN, THE DARKNESS WITHOUT

by TEIKA BELLAMY

Throughout my childhood and a large part of my early adult life I didn’t like my name. It was so obviously foreign, ‘other’, and as most children and young adults come to understand, being different is not desirable.

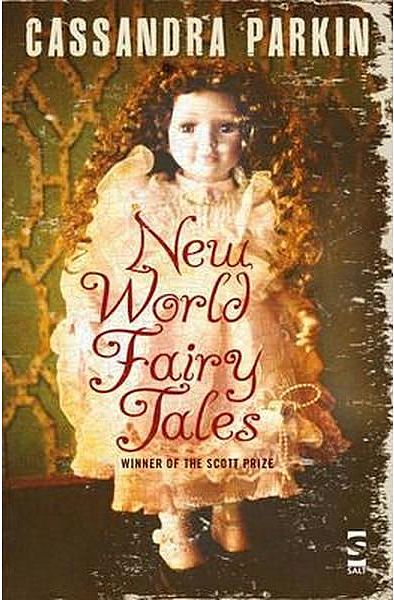

However, when I realised that reading, writing and storytelling were as important to me as breathing, my name, which means ‘fairy tale’ in Latvian (I am half-Latvian and half-Russian), became something to be proud of. It allowed me to make time for my writing; it also gave me the temerity to publish an annual collection of fairy tales for an adult audience (The Forgotten and the Fantastical) through the small press I’d founded. And I know I’m probably overreaching here, because most children enjoy fairy tales, but in retrospect, my name seemed to explain the great love I had for these stories as a child, and why I continued (and continue) to be drawn to contemporary collections of fairy tales for adults. New World Fairy Tales by Cassandra Parkin was one such book that called to me and drew me into its spell.

I had just finished reading Angela Carter’s celebrated collection of re-imagined fairy tales, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories, and although I knew I’d never read anything quite as ravishing as that again, from the moment I began the Scott Prize-winning New World Fairy Tales I was gripped. Each story is an ‘interview’, the premise being that the interviewer (a young, liberal man) is collecting stories from across the U.S. for his college project. As we never hear from the interviewer, only the interviewee, the first person narrative allows the reader to instantly connect with the narrator/protagonist.

The opening story, ‘Interview #4’, is about a modern-day Cinderella – a middle-aged stepmother to two daughters who is as selfless as her daughters are selfish. Yet this Cinderella isn’t simply a meek, momsy widow; she is spirited, sensuous, sexual and sexy. So of course a ‘prince’ can’t help but fall in love with her.

The opening story, ‘Interview #4’, is about a modern-day Cinderella – a middle-aged stepmother to two daughters who is as selfless as her daughters are selfish. Yet this Cinderella isn’t simply a meek, momsy widow; she is spirited, sensuous, sexual and sexy. So of course a ‘prince’ can’t help but fall in love with her.

And then …

…then, the black rubber catsuit held me in a cool, firm embrace. It sculpted and lifted, smoothed and firmed; it clung to every inch of my skin; it was my skin, my new skin, my skin I could wear outdoors. I looked in the mirror, and laughed out loud.…

Crowds parted as I walked down the street, tall in shiny black heels. The doorman bowed. As I entered the ballroom, a respectful silence fell.

The story of ‘Cinderella’ is often dismissed as being irrelevant in the modern world where (apparently) the battle for equality of the sexes has been won, but ‘Cinderella’ still speaks to many of us because, at heart, it bears the hallmarks of what makes for a good fairy tale or ‘märchen’ (the German for ‘folkloric tale’). In the introduction to Black Thorn, White Rose, a collection of adult fairy tales edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, the editors discuss the relevance of fairy tales:

The power of märchen, and the reason they have endured in virtually every culture around the globe for centuries, is due to this ability to confront unflinchingly the darkness that lies outside the front door, and inside our own hearts. The old tales begin Once upon a time… yet they speak to us about our own lives here and now, using rich archetypal imagery and a language that is deceptively simple, a poetry distilled through the centuries and generations of storytellers.

‘Cinderella’ is about the darkness that lies outside the front door (which then comes inside i.e. within the home). The story of ‘Cinderella’ is really about battling with the self-centredness of those who are, purportedly, meant to care about our emotional wellbeing. Many humans desire, and need, romantic love, so to squash a supposedly loved one’s sexual and romantic needs is a cruel act. Cinderella’s family are bullies, yet with the help of someone – the fairy godmother – willing to support her in meeting her need for love, romance (and yes, sex), she is able to overcome the ‘darkness outside’.

‘Interview #9’, the second story in Parkin’s collection is one of the most successful re-workings of a tale by the Grimms that I’ve ever read. On the face of it, the story of ‘The Three Little Pigs’ is uninspiring, yet in New World Fairy Tales Parkin transforms it into something utterly remarkable.

The three pigs are Henry, Mike and Randy – white Louisiana cops who have recently shot dead three innocent black men. Then one day a wolf, in the form of the beautiful black Marilena, comes a-knocking at their homes. She is looking to avenge the deaths of the three innocent men. A gripping chase through the otherworldly Bayou follows. Mike and Randy don’t make it – as to be expected – but Henry, ah, horrible Henry survives. It is here, in Henry, that Parkin shows her real skill for characterisation, for though Henry is thoroughly unpleasant she somehow makes him sympathetic.

I did shoot Ben Arbuckle because I was pissed off and too hot and I’d had enough. I thought he was Robaire Lebrun, but that don’t make it right. We all chose the tune we danced to. Now we got to pay the piper.

“Henry, I always knew you were the smart one,” she said. She was holding the last bomb in her hand, tossing it thoughtfully up and down, that blister quivering like jelly. “You might be a fat middle-aged redneck, but that’s okay by me…”

Henry is saved because someone special believes he is not a monster; that he is worthy of redemption because a light, though feeble, shines within the darkness of his soul. For all his darkness, I am glad that remorseful Henry survived.

‘Interview #15’ is a reworking of the story of ‘Rapunzel’. This contemporary Rapunzel, Cornelia, is of mixed race – her father a Cherokee Indian, her mother white – and she is trapped by the one thing about her that is considered beautiful, her hair. When Cornelia was a child, a teacher had once told her classmates that everyone ‘has something beautiful about them’. Yet when she had looked at Cornelia she had struggled to find anything beautiful apart from her hair. Later, she ponders: ‘Do you know the most insulting compliment you can pay a woman? Tell her she’s got beautiful hair.’

Cornelia goes on to chronicle her battle with the darkness without, in the form of the jealous, witchy Amaranth, the owner of the art gallery where Cornelia works, as well as the darkness within – her otherness and the insecurity that otherness brings: ‘Was I happier with my father? I suppose I was less unhappy, less conscious of what a misfit I was.’

But it is in the world of art, specifically sculpting, where she finds her place. Cornelia is a wonderful, strong protagonist; again Parkin excels at creating a fascinating though real character.

‘Interview #17’ and ‘Interview #27’ – reinterpretations of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ and ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ have ‘the darkness within’ at the heart of the tale. Jack is now a Wall Street financial wizard, with neo-liberalism a backdrop to the story, and it is crude, ugly greed that is Jack’s downfall. In ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ everyone in this glittering Hollywood-set story is downright dark and ugly on the inside: ‘Tinseltown’s harshest critics are its PIs, turning the icons of our age back into the ordinary flesh and blood they secretly always knew they were.’

It is in the final story, ‘Interview #42’, based on ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ that we see a lighter tone, with love and goodness triumphing over the darkness without. The dwarfs – strippers to boot – are the caring little people who help reunite Paul and Jakey after Jakey’s wicked stepmother, disgusted by her stepson’s homosexuality, causes the young lovers to separate. A dangerous apple is still a feature.

Parkin, of course, acknowledges the Grimms – ‘on whose mighty shoulders I have had the temerity to stand’ as is to be expected, because with any reinterpretation of a fairy tale there is the sense that the hard work, the foundations of the story – the plot and players – have already been created; yet these re-workings work for the very reason that the backdrops are so different and rich, compelling and so very real, the pace spot-on and the darkness within and without given just the right amount of shading.

There will always be a place for fairy tales, because the darkness within and without will never go away. It is only when us humans reach a state of utopia within and without that they will cease to exist. Sadly, and although it’s 2017, I can’t see that happening anytime soon.

~

Teika Bellamy is a UK-based mother-of-two, ex-scientist, writer and artist. She is the founder of the indie press, Mother’s Milk Books. Under her pen-name, Marija Smits, she writes poetry and fiction; her work has appeared in Mslexia, Brittle Star, Strix, Literary Mama and LossLit. She is constantly delighted by the fact that Teika means ‘fairy tale’ in Latvian. She can be found at: https://marijasmits.wordpress.

One thought on “The Darkness Within, The Darkness Without”

Comments are closed.