('In A Box'© Giuseppe Milo, 2017)

In this essay, shortlisted in the 2018 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Sam Reese looks at the blurred lines between biography and fiction in the short stories of Mary McCarthy.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘This profile offers a fresh and timely re-consideration of McCarthy’s stories, offering us a keen sense of her daring, her psychological insights, her formal innovation, and of her inspiring tendency to buck trends. The piece also celebrates the short story’s innate power to ‘make it new’, to startle us with fresh perspectives, and to subvert the rigid social codes that try to define us before we ourselves can.’

‘Very well argued – intelligent and alert to the idea of the story cycle.’

‘A really thoughtful and well-argued essay. In particular, the deft way in which the writer weaves in the idea of identity as shaped by narrative make this a very stimulating read.’

‘A fascinating essay, which makes intelligent points about McCarthy’s feminism, and which explores the genre of the ‘story-cycle’ in a pleasing fashion.’

~

Hailing from New Zealand, Sam Reese is an insatiable traveller. Having worked in Sydney and London he currently lives in York, teaching English and Creative Writing at the University of Northampton. A self-confessed short story nerd, he has published stories in Storgy, Brittle Star and Headland, and won AZURE’s January 2018 Writing Contest. He also writes literary criticism; his first book, The Short Story in Midcentury America, was published with Louisiana State University Press, and won the Arthur Miller Centre First Book Prize (2018).

Hailing from New Zealand, Sam Reese is an insatiable traveller. Having worked in Sydney and London he currently lives in York, teaching English and Creative Writing at the University of Northampton. A self-confessed short story nerd, he has published stories in Storgy, Brittle Star and Headland, and won AZURE’s January 2018 Writing Contest. He also writes literary criticism; his first book, The Short Story in Midcentury America, was published with Louisiana State University Press, and won the Arthur Miller Centre First Book Prize (2018).

~

THE COLD EYE OF MARY MCCARTHY

by SAM REESE

Like many of her peers in mid-century America, Mary McCarthy is now mostly remembered for her acerbic wit and pithy, public insults. “Every word she writes is a lie,” she once famously declared of playwright Lillian Hellman, “Including ‘and’ and ‘the’.” This sardonic gaze—just as frequently turned on herself as on her contemporaries—gave McCarthy’s prose a distinctively ironic flair. When her fiction is discussed today, it is therefore normally presented as a case study in social satire.

Yet as her interviews and fiction attest, McCarthy was also capable of great warmth and care—particularly towards her characters. Indeed, one of her most-repeated epigrams, originally uttered in an interview for The Paris Review, shows how closely life and fiction intertwined in her vision of the world: “we all live in suspense, from day to day, from hour to hour; in other words, we are the hero of our own story.” A cynic might see this as just another sign of McCarthy’s self-obsession, but I think that it instead reveals one of her greatest insights as a writer—identity is shaped by narrative, and the way we see the story of our life can either free us or confine us.

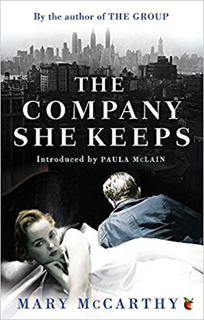

Certainly, McCarthy’s two short story collections—The Company She Keeps (1942) and Cast a Cold Eye (1950)—focus almost obsessively on the act of self-narration. The protagonists write diaries, visit therapists, and have existential crises following one-night stands on trans-continental train-trips. These stories also, notoriously, blur the line between fiction and autobiography. In 1957, McCarthy solidified her status as one of the foremost public intellectuals and social commentators with the publication of her memoir, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. Yet several of the chapters in this book had already been published individually, presented as short stories and, as the Columbia Companion to the Twentieth-Century American Short Story notes, the autobiography shares many ‘characteristics and themes’ with McCarthy’s debut collection, The Company She Keeps. From her first stories, then, McCarthy deliberately played with the boundaries between character and author, calling into question the idea of fixed identity.

Certainly, McCarthy’s two short story collections—The Company She Keeps (1942) and Cast a Cold Eye (1950)—focus almost obsessively on the act of self-narration. The protagonists write diaries, visit therapists, and have existential crises following one-night stands on trans-continental train-trips. These stories also, notoriously, blur the line between fiction and autobiography. In 1957, McCarthy solidified her status as one of the foremost public intellectuals and social commentators with the publication of her memoir, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. Yet several of the chapters in this book had already been published individually, presented as short stories and, as the Columbia Companion to the Twentieth-Century American Short Story notes, the autobiography shares many ‘characteristics and themes’ with McCarthy’s debut collection, The Company She Keeps. From her first stories, then, McCarthy deliberately played with the boundaries between character and author, calling into question the idea of fixed identity.

Throughout her life, in fact, McCarthy refused to let herself be confined, whether by social convention or the dictates of genre. Born in Seattle in 1912, she established her career—and honed her wit—as a theatre reviewer, before finding early success through a series of articles for The Nation that she intended as ‘large-scale attack on critics and book-reviewers.’ By the time of her death in 1989, she had published eighteen books, which spanned short fiction, the novel, the essay, journalism, and memoir; the 2018 re-issue of her novel Birds of America rightly points to her as ‘one of the most celebrated writers of her generation.’

But for all her skill at longer forms, throughout her career McCarthy consistently proved that it was short, compressed prose she had truly mastered. Even her most widely read work, the 1963 novel The Group, is actually constructed as a series of linked stories. The novel continues to enjoy a scandalous reputation and, used as a prop, it has become a visual shorthand in film and television for a character’s progressive thinking about female sexuality. But when Norman Mailer criticised The Group as a failed ‘collective novel,’ he may have had a point—not because the writing itself fails, but because each of the ‘chapters’ has the formal coherence and independence of a well-crafted short story.

From this perspective, it is probably not surprising that, of all her assorted publications, it was McCarthy’s first collection that had the most pronounced impact on literary culture; the effects of The Company She Keeps were unmistakeable, both in the immediate wake of its publication, and over the long term. Almost straight away, McCarthy opened up a public space for new fictional discourse around female sexuality, reflected in a rush of stories echoing her style in magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and The New Yorker. But writers also continue to turn to the stories’ heroine, Meg Sargent, for inspiration in crafting conflicted, self-aware protagonists—whose sexual agency does not restrict the roles they can play.

McCarthy’s stories certainly stand out for their frank depiction of casual relationships. The collection’s most widely republished piece, ‘The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt’, openly exposes the pitfalls of an affair that starts off as a one-night stand in a Pullman carriage—crucially, without belittling the protagonist in the process. This story, originally published in 1941 in Partisan Review, gave the reading public their first introduction to Meg Sargent, the central character in each of the stories in The Company She Keeps. Her wry assessment of the Ivy-League businessman who steps into her carriage reflects McCarthy’s trademark irony: although Meg decides he looks ‘like a middle-aged baby, like a young pig, like something in a seed catalogue’ and affirms that ‘he was plainly Out of the Question,’ by the next morning she still finds herself searching frantically around his compartment for her strewn garments.

However, the story does more than provide a social satire on contemporary relationships, or simply pave the way for other explorations of female desire. McCarthy carefully and critically unpacks the way that Meg’s identity is constrained, even at the points where she seems to be most in control of her own story. So the initial freedom that she feels on board the train, outside the normal social conditions, is replaced with a slowly dawning recognition of the limitations that this new relationship places on her identity. In what might be considered a neurotic register, she obsesses about roles, types, and classifications; at one point she admits that she is interested in the eponymous man because he might be ‘the one who could tell her what she was really like.’ And the story is charged with an almost schizoid dynamic, as she longs for the man to confirm her identity but resists the characterisations he tries to impose on her.

Across the collection McCarthy’s female characters find themselves caught between the desire to escape the conventional, the socially accepted, even as they are irresistibly drawn to people or situations—lovers, employers, psychiatrists—who can help give definition to their sense of self. This is hardly an indictment of women; McCarthy’s ironic register ensures the reader never starts to think that these characters actually need men to tell them what they can be. Instead, it is an exposé of cultural narratives that limit or constrain. This is why, rather than linking these six stories as a novel, as she did in The Group, McCarthy breaks Meg’s experiences into clearly delineated, self-contained tales.

This formal innovation has perhaps been even more important to the development of the short story form than McCarthy’s taboo-breaking subject matter or arch wit. By the early 1940s the concept of a short story cycle was hardly revolutionary. But the idea of taking the same central character and analysing her experiences from six radically different perspectives—so that, despite variations on the same name, the protagonist is sometimes unrecognisable between the stories—was both new and, for many readers, quite unsettling. One contemporary critic described McCarthy as having ‘photographically and psychologically “shot” her heroine from six angles’, and while his review acknowledges the skill with which McCarthy executes this approach, he concludes that the effect was disturbing: ‘the book is almost too penetrating’, giving ‘the uneasy feeling of [the reader themselves] being under an X-ray.’

This formal innovation has perhaps been even more important to the development of the short story form than McCarthy’s taboo-breaking subject matter or arch wit. By the early 1940s the concept of a short story cycle was hardly revolutionary. But the idea of taking the same central character and analysing her experiences from six radically different perspectives—so that, despite variations on the same name, the protagonist is sometimes unrecognisable between the stories—was both new and, for many readers, quite unsettling. One contemporary critic described McCarthy as having ‘photographically and psychologically “shot” her heroine from six angles’, and while his review acknowledges the skill with which McCarthy executes this approach, he concludes that the effect was disturbing: ‘the book is almost too penetrating’, giving ‘the uneasy feeling of [the reader themselves] being under an X-ray.’

To understand why many reviewers (whose views are at least better documented than those of the average reader) found this formal experimentation so unsettling, it is worth thinking about the traditional relationship between the novel and identity. For decades, critics had been drawing comparisons between the growth of individual identity and the narrative progression of the realist novel; this assumption helps explain why Mailer found The Group so unsuccessful as a novel. Even as early as The Company She Keeps, McCarthy destabilises and undermines a coherent model of identity.

Rather than a rational series of events through which her heroine grows and develops a clearer understanding of her world and her own place in it, The Company She Keeps presents a fractured protagonist, whose individual ‘episodes’ are disjointed and fragmented. Well aware of the relationship between narrative and identity, McCarthy uses the vital compression of the short story form as a way to offer an alternative view of the roles available to contemporary women. Rather than attending to traditional character development, McCarthy instead focuses almost obsessively on her characters’ conformity to various types and classifications, to suggest the extent to which behaviour is patterned and conditioned by social settings. More than this, the sharpest (and saddest) moments in the book are when this strong, intelligent woman reveals how much she has internalised social expectations about her gender.In the final story, Meg recognises that she has ‘been under a terrible enchantment,’ seeing herself as one of the ‘beleaguered princesses in the fairy tales.’ Although she had believed she was able to shift freely between roles, in the final assessment she believes she ‘was not truly protean but only appeared so.’

Aside from its brilliant prose, The Company She Keeps is important for what it says about how we are all still limited and defined by the expectations of others—constrained by our company. The current tendency to see her as a satirist does her work an injustice. Yes, there are some brilliant critiques of the New York intelligentsia in Cast a Cold Eye—to say nothing of her biting 1949 novella, The Oasis—but her formal innovations as a short story writer remain radical, even amid 21st-century experimentation. McCarthy herself was sceptical of the idea of social progress; one of her aims in The Group was to expose how little, by the 1960s, life had improved when compared to the period of the Great Depression. This helps to explain why, even in one of her longest works, The Group, she returns to the aesthetic containment of her earliest short fiction. McCarthy understood the short story’s power to, at once, validate the individual, and to expose the social forces that hold them back.

Super essay. Congratulations. I read “The Group” at the age of 14 in the 1960s, copied relevant pages by hand to other girls I knew, and never got to her other work until later.