photo cropped © Matthias Lueger, 2015

by Professor Charles E. May

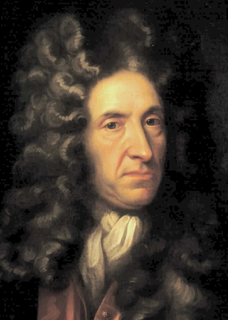

Most literary historians agree that the short story originated in America in the nineteenth century — popularly with the phenomenal success of Washington Irving‘s The Sketchbook in l819, and critically with the publication of Poe‘s famous review of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales in 1842. Some critics suggest that the form began with Ludwig Tieck’s Fair Eckbert at the turn of the century in Germany, while still others point to Prosper Merimee‘s Mateo Falcone in France in 1829 or Pushkin’s Tales of Belkin in Russia in 1831. Nowhere does anyone suggest that the short story began in England. Perhaps this is because critics have ignored the generic characteristics of Daniel Defoe’s ‘A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs. Veal’ (1706). In an era that saw the development of the new realism and the rise of the novel that dominated English fiction throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this short piece clearly indicates the separation between two basic forms of fiction — narratives presented ‘as if’ the events actually took place and narratives presented as inventions or mental projections. ‘A True Relation’ confronts the issue of ‘fact’ versus ‘fiction’ so emphatically that it can serve as a model for how early short fiction dealt with these conventions.

There is little or no ‘plot’ to the story. It simply recounts a visit that Mrs. Veal — a thirty-year-old maiden gentlewoman — pays to her old friend Mrs. Bargrave, which would be of little interest except for the fact that the visit takes place on the day following Mrs. Veal’s death.

At first, the piece was considered a simple fabrication created by Defoe to advance the sale of a popular theological work, Charles Drelincourt‘s On Death, and in fact the ‘True Relation’ was often appended to Drelincourt’s work. From this point of view, Defoe’s story can be seen as a variant of the typical eighteenth-century narrative written to illustrate a moral. However, the story has most often been discussed as an early example of the kind of realistic conventions Defoe used to help establish the novel as a viable narrative form. From this point of view, the story becomes interesting as an exercise in verisimilitude, a footnote to the methods and origins of the realistic novel.

In addition to being cited as an early example of the old moral tale and the new narrative of verisimilitude, ‘A True Relation’ has also been called an example of the gothic mode that began to dominate English short fiction at the turn of the century. From this perspective, the piece is worth considering for the manner in which it presents the kind of ghostly apparition that, before the eighteenth century, might well have been accepted in folklore stories as an article of belief. Thus, the story attempts to validate what did not need to be validated before. Defoe tries to retain the antirealist significance of the romance form within a culture in which the spiritual significance of the old legends, ballads, and folk-tales was no longer tenable. Modes of validation, such as the common nineteenth century convention of presenting an eye-witness account, dominate the story. The eye-witness account, which the dramatized ‘author’ can claim is ‘truth’ because he is presenting it just as he received it, is complicated in ‘Mrs. Veal’ because the piece includes both oral and written modes of discourse.

‘A True Relation’ therefore looks backward to the most traditional form of short narrative — the fable presented to teach a moral lesson — and forward to the realistic story presented for its own sake as an account of an actual event. To see it as the first kind of story is to see it as being motivated primarily by the metaphoric significance of the moral lesson in order to convince the reader of its spiritual truth. To see it as the second kind is to see it motivated by realistic detail for the purpose of convincing the reader of its truth to physical reality. What makes ‘A True Relation’ historically interesting is that it foregrounds this duality so emphatically.

‘A True Relation’ therefore looks backward to the most traditional form of short narrative — the fable presented to teach a moral lesson — and forward to the realistic story presented for its own sake as an account of an actual event. To see it as the first kind of story is to see it as being motivated primarily by the metaphoric significance of the moral lesson in order to convince the reader of its spiritual truth. To see it as the second kind is to see it motivated by realistic detail for the purpose of convincing the reader of its truth to physical reality. What makes ‘A True Relation’ historically interesting is that it foregrounds this duality so emphatically.

The short preface to the story insists that the ‘relation’ is ‘matter of fact, and attended with such circumstances as may induce any reasonable man to believe it’. Indeed the basic issue here that separates the story from earlier accounts of the supernatural is that it appeals to a conviction governed by reason rather than a belief governed by superstition. The eyewitness, Mrs. Bargrave, tells the story to a neighbour woman, who then tells it to a kinsman, who then tells it to a justice of the peace, who writes it down and sends it to a friend in London. The narrative is thus filtered from the eyewitness through two speakers and then two different writers who create and transmit the manuscript. We are not told whether the friend in London is the one who submits it to print or not. Both the neighbour woman ‘teller’ and the justice of the peace ‘writer’ are attested to as intelligent and discerning people, who present the story as being in the same words that the neighbour woman had from Mrs. Bargrave’s own mouth – “as near as may be” – and that Mrs. Bargrave had no reason to invent the story, being a woman of honesty, virtue, and piety. The writer of the preface then insists that the ‘use’ to which we should put the ‘relation’ is a conventional moral one; that is, that there is life to come and a just God who will mete out rewards and retribution; therefore, we should live in such a way that may be pleasing to God.

Although Defoe did not invent the supposed ghostly encounter, he did invent the oral narrator, the neighbour woman who supplies us with more information than about the encounter itself; it is this additional information that creates a context for the central event which makes the issue of fact or fiction in the piece more interesting than simply the fact or fiction of the apparition itself. For example, the narrator tells us that Mrs. Bargrave and Mrs. Veal are not only childhood friends, but that they both had unkind fathers and that Mrs. Veal considers Mrs. Bargrave her only friend in the world. In addition, we are told that Mrs. Bargrave has a wicked husband from whom she suffers and that Mrs. Veal is under the care of a brother because she is given to fits that make her deviate ‘from her discourses very abruptly to some impertinence’. Because this information is not central to the basic issue either of the truth of the story or the moral lesson, we may take these details as either thematically ‘free’ motifs, that is, irrelevant except in terms of verisimilitude, or we may take them to be thematically ‘bound’ motifs, that is, relevant to the structure and meaning of the story in a way that previous critics have ignored.

The nature of discourse is of course the central subject of the story, not only in the conversation or discourse in which Mrs. Veal engages with Mrs. Bargrave, but also in the contextual frame story. In the actual encounter, Mrs. Veal has Mrs. Bargrave run and fetch two kinds of discourse — first the copy of Drelincourt’s On Death, which they have read and discussed before, and then some verses that Mrs. Bargrave has copied down in her own hand from Friendship in Perfection. Mrs. Veal’s own discourse is itself about discourse: first she talks about Drelincourt’s book to comfort Mrs. Bargrave that her current affliction under her wicked husband shall be removed from her in Heaven, and then she talks about the writings of the ‘primitive Christians’ which, unlike the ‘frothy, vain discourse’ of the current age, was for edification. At this point there is an abrupt shift from ‘heavenly’ discourse to legal discourse — a letter that Mrs. Veal wants Mrs. Bargrave to write to her brother, telling him that she wishes certain rings and a purse of gold to be left to acquaintances.

The ‘relation’ of the actual visit and the discourse of Mrs. Veal accounts for less than half the piece. The remainder deals with the context. Thus, fully as much of the piece is about the telling of the story as it is about the story itself. Therefore, it seems clear that the subject of the story is not the apparition of Mrs. Veal, but the ‘relation’ of the apparition. First there is the explicit question of the truth of Mrs. Bargrave’s relation of the incident, which is questioned by Mrs. Veal’s brother, who insists that it is a ‘reflection’. Although the meaning of this term is not clear in the story, it seems to suggest the opposite of ‘true relation’, and therefore suggests the Lockean view that knowledge either comes from sensation or from ‘reflection’, that is, from the external world or from the mind itself.

The issue of physical truth versus mental truth is also raised by Mrs. Veal’s brother when he insists that while Mrs. Bargrave may not be lying, she has been ‘crazed’ by her cruel husband. This dichotomy of mental versus physical is also mentioned in Mrs. Veal’s discourse when she laments to Mrs. Bargrave about the eyes of faith not being as open as the eyes of the body. It is a motif suggested by the narrator when she notes that those who first hear Mrs. Bargrave’s story satisfy themselves that she is no hypochondriac; that is, she is not affected by vapours from the hypochondria, not a melancholy person who confuses the physical with the mental.

The issue of physical truth versus mental truth is also raised by Mrs. Veal’s brother when he insists that while Mrs. Bargrave may not be lying, she has been ‘crazed’ by her cruel husband. This dichotomy of mental versus physical is also mentioned in Mrs. Veal’s discourse when she laments to Mrs. Bargrave about the eyes of faith not being as open as the eyes of the body. It is a motif suggested by the narrator when she notes that those who first hear Mrs. Bargrave’s story satisfy themselves that she is no hypochondriac; that is, she is not affected by vapours from the hypochondria, not a melancholy person who confuses the physical with the mental.

It little matters, in terms of the technique of the tale, whether the apparition actually appeared to Mrs. Bargrave or not, nor does it matter that Defoe takes the incident from an actual account by Mrs. Bargrave. What does matter is the process by which the relation becomes a story. ‘A True Relation’ becomes a story through the dual means by which all accounts become stories — by being aware of itself as ‘relation’ rather than ‘event’ and by being unified or held together through repeated motifs that constitute its theme, in this case the psychological theme of mental versus physical events. This thematic content suggests the basic dichotomy between events described as if they actually took place and events presented as pure projections of the mind, that is, the dichotomy between romance and realism. Whether an event actually took place or whether a central character or narrator is crazed and has simply hallucinated the event is one of the most common foregrounded concerns of short fiction in the nineteenth century.

The authority for the event (for after all, short fiction usually presents an event rather than an abstraction based on events) has been central to short fiction since Boccaccio, the ‘truth’ of whose tales was predicated on the teller having heard them from someone else who attests to their validity as having actually happened. Short fiction lies between the romance convention of presenting marvelous events and the realistic convention of presenting events as if they actually happened, even though the events themselves depart from the ordinary course of things.

‘A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs. Veal’ raises issues about the nature of discourse, the modes of discourse, the uses of discourse, and the means of transmission of discourse that dominate the short fiction form throughout the nineteenth century. What makes Defoe’s piece a story is its own foregrounded focus on itself as a ‘relation’ of an event which can be accounted for by the appeal both to the techniques of realism and the thematics of romance, that is, by the presentation of an experience as being both ambiguously actual event and a mental projection. This crucial ambiguity, bound up in a tight thematic unity of interwoven motifs, characterises the stories of Hawthorne and Poe, commonly thought to mark the beginning of the short story form. Such narrative experimentation, however, did not spring full-grown from the imagination of American writers, but rather derived from the self-conscious explorations of Daniel Defoe.

One of my favourite short stories is ‘The Cobbler Blondeau,’ attributed to Bonaventure Des Perriers (d.1544) and found in volume III of Hammerton’s The World’s Thousand Best Short Stories. (the previous two volumes cover earlier stories).