photo © Jose Wolff, 2008

by Victoria Heath

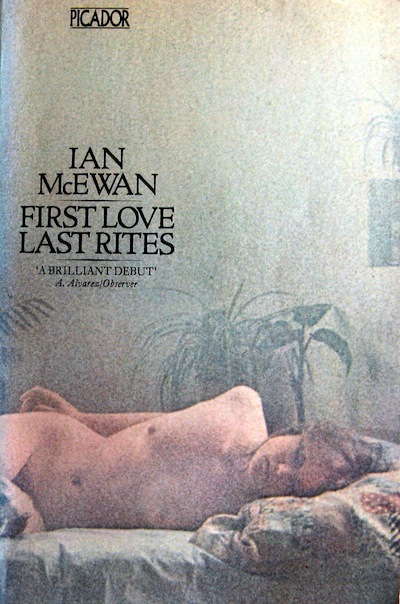

Youth. Sex. Heat. An off-putting younger brother. Pink nylon uniforms. Eels. And an incessant scratching in the walls. An unusual combination for a love story, but the ingredients that make up Ian McEwan’s ‘First Love, Last Rites’.

I first read this story as a teenager. I’m not sure I appreciated it fully back then, but I adored it nonetheless, particularly the romantic ideal of the opening line: ‘From the beginning of summer until it seemed pointless, we lifted the thin mattress on to the heavy oak table and made love in front of the large window.’ Even now, almost twenty years on, that image still gives so much. What I got from it back then was a dreamy, teenage view of the future, that perfect ‘first love’. What I revel in now is not the dreaminess of the moment but the simplicity of language. With these simple adjectives – ‘thin’, ‘heavy’, ‘large’ – McEwan creates a vivid image of space and passion without any fuss, while the weight of the word ‘pointless’ hints that this isn’t going to be a story of perfect love.

The story tells how Sissel and the seventeen/eighteen-year-old unnamed narrator spend the days of early summer having sex. Then, one day, the boy hears a noise in their room and he starts listening ‘to it scrabbling in the silence’. The ‘it’ is often referred to more sinisterly as the ‘creature’ and it’s the crux that McEwan uses to turn this story from that of a starry-eyed relationship into something darker and far more interesting.

As the summer moves forward, whenever they have sex, the narrator begins to fixate on fantasies of this ‘creature’ in the walls. The couple have agreed that the narrator will withdraw before climax, but these fantastic images have such power over him that they lead him to come prematurely.

…once I was inside her I was moved, I was inside my fantasy, there could be no separation now of my mushrooming sensations from my knowledge that we could make a creature grow in Sissel’s belly. I had no wish to be a father, that was not in it at all. It was eggs, sperms, chromosomes, feathers, gills, claws, inches from my cock’s end the unstoppable chemistry of a creature growing out of a dark red slime…

It is his helplessness in the situation, in the creation of a baby, that takes over him in these climatic moments. A feeling everyone can probably relate to, though perhaps not as extremely. This is linked directly with his powerlessness over the scratching creature in the walls; he cannot help but obsess. At first, the narrator believes the scratching is only in his head, but then Sissel hears it too and he begins to worry, thinking it is a sound that grows ‘out of our love making’.

We heard it when we were finished and lying quite still on our backs, when we were empty and clear, perfectly quiet. It was the impression of small claws scratching blindly against a wall.

When they try to find the source of the noise, it goes silent, ‘frozen in its action, waiting in the dark’. The imagery McEwan creates in these scenes is superbly unreal. Though we know, and the characters know, it is most likely a mouse, McEwan encourages the imagination to conjure all kinds of possibilities, heightening the tension in the story and gently illustrating the obsessive nature of the protagonist.

When they try to find the source of the noise, it goes silent, ‘frozen in its action, waiting in the dark’. The imagery McEwan creates in these scenes is superbly unreal. Though we know, and the characters know, it is most likely a mouse, McEwan encourages the imagination to conjure all kinds of possibilities, heightening the tension in the story and gently illustrating the obsessive nature of the protagonist.

As the summer goes on, not only does the scratching become more persistent, but the young couple’s relationship also becomes more intense, more real. McEwan leaves behind those images of sex by an open window and concentrates on some of the harsher, less romantic realities of this first love. He writes graphically of ‘good and sticky and brown’ sex when Sissel has her period. He shows us Sissel’s foot rot, flies biting their armpits, rising ‘mushy heat’, the smell of dead jellyfish. And we see noisy, boisterous interruptions from Sissel’s younger brother, Adrian, who visits to escape ‘the misery of his disintegrating home’. Dragging the mattress up to the window has now become ‘pointless’, as the opening line foresaw.

By mid-July, the lovers aren’t as happy: ‘There was a growing dishevelment and unease, and it did not seem possible to discuss it with Sissel.’ Every night the scratching behind the wall wakes them. During the day, the couple start to spend less and less time together. The narrator takes long walks alone. He forces himself to make eel nets – a venture Sissel’s father has encouraged – in order to try and catch enough eels to sell, though he knows in his heart it’s fruitless work. Then, when Sissel finds a job, the narrator comes to the realisation that ‘we were different from no one’. The fantasy of his first love is gone.

Here, McEwan has well and truly broken the romantic spell of the opening and it feels more real than that initial image. How long can the honeymoon period really last, even for teenagers? He takes it further still, using another very simple scenario to show how fragile this first love is. On Sissel’s second day at work, the narrator goes to meet her at the factory gates, but when the workers leave he can’t pick her out from the crowd of women in their identical pink, nylon uniforms. It becomes very important to him to spot her, thinking that if he couldn’t ‘we were both lost and our time was worthless’. He leaves before his self-professed fate is sealed, but when he gets home, Sissel is already back. She saw him at the factory gates and claims she ‘didn’t think’ to go over to him. ‘Her words had a deadening finality, I glanced around our room and fell silent.’

The narrator goes out with Sissel’s father to check the eel traps he’s made. They find only one eel, and the majority of the traps have been washed away. Sissel’s father suggests another venture for the narrator, driving van loads of cheaply bought shrimp to Brussels and selling them at a higher price. It’s a light aside from McEwan, where we can identify with the narrator – everyone knows a schemer like this – and it gently balances the weight of the narrative and what’s to come. When he gets back home, the narrator finds Sissel ‘staring into one corner of the room’.

It’s in here, she said. It’s behind those books on the floor. I sat down on the bed and took off my wet shoes and socks. The mouse? You mean you heard the mouse? Sissel spoke quietly. It’s a rat. I saw it run across the room, and it’s a rat.

McEwan describes this rodent with hyperbole, taking that unreality of the narrator’s fantasies and pushing us to see this simple rat through his eyes. He is terrified, unable to move; it’s the size of a ‘small dog’, ‘squat’, ‘powerful’ and ‘dragging its belly along the floor’.

Then Adrian arrives, with his ‘familiar stamping, machine-gunning noise’ and the tension is lifted again, briefly. Adrian is excited by the prospect of a rat to kill and he and the narrator boyishly create a kind of fort from books, boxing the rat in behind the chest of drawers with only one escape route. Adrian urges it out from its hiding place and the narrator stands ready with a poker in hand.

Sure enough, the rat runs out and McEwan shows us its ‘teeth bared and ready’, ‘how powerful and fat and fast it was’, ‘how its tail slid behind it like an attendant parasite’. He makes it even more horrible than a rat need be, because we’re seeing it through the imaginative narrator’s eyes, but then Sissel interrupts. She doesn’t want the thing killed and she screams at the narrator to drop the poker, pulling on his arm. He persists, though, and on a second attempt, he brings the poker down and catches the rat ‘clean and whole smack under its belly’. The thing flies through the air and when it lands it is ‘split from end to end like a ripe fruit’. The three human characters are all as breathless as the rat, unable to move.

Sure enough, the rat runs out and McEwan shows us its ‘teeth bared and ready’, ‘how powerful and fat and fast it was’, ‘how its tail slid behind it like an attendant parasite’. He makes it even more horrible than a rat need be, because we’re seeing it through the imaginative narrator’s eyes, but then Sissel interrupts. She doesn’t want the thing killed and she screams at the narrator to drop the poker, pulling on his arm. He persists, though, and on a second attempt, he brings the poker down and catches the rat ‘clean and whole smack under its belly’. The thing flies through the air and when it lands it is ‘split from end to end like a ripe fruit’. The three human characters are all as breathless as the rat, unable to move.

After a while, the narrator prods the rat with the poker and from its belly slides ‘a translucent purple bag, and inside five pale crouching shapes, their knees drawn up around their chins’. The significance of these babies, linking back to the narrator’s thoughts of impregnating Sissel, instantly settles the story. The excitement is broken, as is the tension, and a surreal calmness takes over as they place the rat and babies in the dustbin and then set the narrator’s single eel free in the quay.

Adrian leaves for a holiday with his father and the story closes as it began. The couple lift the mattress on to the table. They are alone. The heat has subsided. And the scratching is gone. They lie and talk. Sissel will quit her factory job. They decide to tidy the room and go for a walk.

It’s a serene kind of ending. That idyllic image of first love has returned, but it’s more peaceful and real now. It’s not the dreamy scenario that opened the story, because now they have the memory of the scratching and death hanging over them. Instead, a kind of calm has settled on the couple. Sex isn’t their priority any more. They are going to go for a walk. They have changed. It’s almost a coming of age story, fitted neatly into just eleven pages.

This story made a lasting impression on me as a teenager – rather aptly, if a little sickly, my first short fiction love. I wasn’t one of those lucky people who always knew they were going to write, but soon after reading ‘First Love, Last Rites’ I started writing short stories myself. I realised how stories could be about very real situations, about the human existence in all its normal, plain glory and that concept really appealed to me. It’s those representations of a simple, identifiable life – prickly, sprouting, stinking warts and all – that really hook me into McEwan’s short stories and that’s what I’ve been trying to capture in my own writing ever since.

~

Formerly a copywriter in the advertising industry, Victoria Heath now works as Editor at Thresholds, reads for a fiction publisher, edits fiction and poetry, and writes short stories. She was awarded the Kate Betts Memorial Prize for her work on the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester. Her stories have been published in the UK and Ireland, and listed and placed for various prizes, including the Bridport Prize and the Labello Press Prize. Unsurprisingly, bookshelves line the walls of almost every room in her house.

~

photo of Ian McEwan © Annalena McAfee