photo by Joseph Younis

by Alex Ruczaj

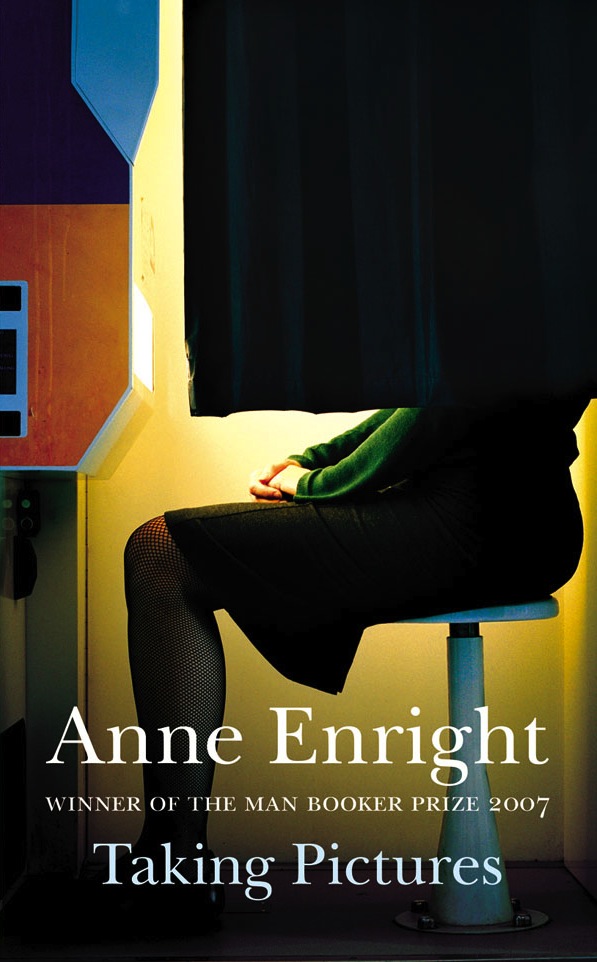

Anne Enright’s collection Taking Pictures inspired my first real writer’s crush. I poured over the pages as I had poured over those of Look-in when I was twelve. Post-it notes of killer lines were scattered over my journal, just as Look-in lyric posters (mainly Nik Kershaw) had once covered my teenage bedroom. Enright’s were the first stories I climbed inside and didn’t want to leave.

The story that initially drew me in was ‘In the Bed Department’, which begins with the line ‘Kitty was suspicious of the escalator…’ I can’t see an escalator now without thinking of that line, without picturing Kitty’s mother ‘sailing down from fabrics and soft furnishings like a queen’. This story in particular had a calming effect on me; whenever I panicked that my stories weren’t about very much at all, it gave me permission to write boldly about ordinary things.

‘In the Bed Department’ is essentially the story of a divorced woman distracted by the escalators in the department store where she works. The story takes place over a few weeks, but Enright spends far more time describing the escalators than she does narrating the main action of the story – namely the sexual act that causes a suspected pregnancy:

It was awkward all the way through, and quite satisfying. Kitty did not tell him about her ex-husband, as he did not talk about his dead wife. She did not tell him that her husband had strayed, that she had done everything to keep him – up to, and including, porn videos in the bedroom – and that when she stormed out, the judge had held that desertion against her and awarded him the house.

This crucial and dramatic back story is skimmed over briefly in summary. It’s expertly done; the specific detail of the porn videos and the court judgement means we understand this relationship and its effect on Kitty. Enright doesn’t need to wave a flag and tell us about Kitty’s loneliness and the heartache she feels after such a cruel end to her marriage. Instead, this story runs subtly beneath the surface, like the chain that Kitty imagines ‘running freely, deep’ beneath the escalator.

That said, Enright isn’t a writer who shies away from drama. As Hermione Lee comments in the Observer, these ‘stories describe the losses, confusions and sexual damage of women’s lives with laconic, savage verve’. Ex-boyfriends go mad and curl up, bony-backed on the bed; sisters go missing and are found dead. Even the woman in the local shop in ‘Wife’ has a ‘livid’ scar across her throat. Yet Enright manages to tell all these stories, whether they are big or small, with a lightness of touch. She tickles you, before she gently reaches down your gullet and rips out your heart.

That said, Enright isn’t a writer who shies away from drama. As Hermione Lee comments in the Observer, these ‘stories describe the losses, confusions and sexual damage of women’s lives with laconic, savage verve’. Ex-boyfriends go mad and curl up, bony-backed on the bed; sisters go missing and are found dead. Even the woman in the local shop in ‘Wife’ has a ‘livid’ scar across her throat. Yet Enright manages to tell all these stories, whether they are big or small, with a lightness of touch. She tickles you, before she gently reaches down your gullet and rips out your heart.

This ability to deal with horrific things in a light way comes down to voice. The first story in Taking Pictures, ‘Pale Hands I Loved, Beside the Shalamar’, starts with the casual throw-away line, ‘I had sex with this guy one Saturday night before Christmas’. The power of the voice is immediate. It demands attention. And, as Al Alvarez advises in The Writer’s Voice, it ‘seems to be speaking directly to you, communing with you in private, right in your ear, and in its own distinctive way’. The narrator describes to us her old roommate, Fintan, who has few faults – apart from a diagnosed mental illness, a chain smoking habit, and a faint body odour issue:

I would get him to wash his clothes more, but I think he is happier with the smell, and so am I. It reminds me of the time when I nearly loved him, back in college when it rained all the time and no one had any heating, and the first thing you did with a man was stick your schnozz into his jumper and inhale.

I am not sure if this is something I remember having done myself, but after reading this I absorbed it as one of my own memories; such is the verisimilitude Enright creates. I can see myself sniffing a gangly student’s scratchy jumper in a cold house in Preston.

I love the voice in this story, and this kind of voice is a constant throughout the collection – all Enright’s protagonists have flaws, a dry humour and emotional insight. In his review of Enright’s novel The Gathering, Adam Mars-Jones referred to the narrator Veronica as ‘strangely good company even at her most negative.’ I think this is an even more admirable achievement in a collection of short stories, yet she succeeds in making each and every one of her narrators different, flawed and yet all good company, in one way or another.

The charm of Enright’s voice enables her to take us to darker places. ‘Pale Hands’ concludes with what could be a sentimental scene in anyone else’s grip. But these words get me every time and have me blubbing almost as much as Kershaw’s ‘Save the Whale’.

I meet Fintan in the afternoons and we have sex as sweet as rainwater. […] He is madder now than he ever was. I think he is quite mad. He is barely there. Behind my back I hear the sound of threads snapping. I turn to him, curled up on the sheet in the afternoon light, the line of bones knuckling his back, the sinews curving up behind his knees and – trembling on the pillow, casually strewn – the most beautiful pair of hands in the world.

‘Honey’ is another gut-wrencher and centres around a business trip taken by the character Catharine. The story returns to one of Enright’s favoured subjects, and the focus of her novel The Forgotten Waltz – an affair. Catharine is married and ends up sleeping with business colleague Phil, but close to the beginning of the story, we are also presented with the parallel story of her mother’s illness:

And then in the hospital, when the pain relief was good, such peace: her mother existing – breath by breath – at her side. Both of them listening to her body, the silent chemicals doing their silent work, and the dent on the side of her breast, the largest thing in the room.

No funny lines here. But there’s a subtle wryness to the voice overall. It isn’t simply grief for her mother that causes Catherine to sleep with Phil. She sleeps with him – a man she has no respect for – as a way of consuming and devouring life after facing so much illness and death. Enright gives us a nuanced and complex character and her motivations make us read urgently and hungrily whilst thinking, ‘Don’t sleep with him!’

No funny lines here. But there’s a subtle wryness to the voice overall. It isn’t simply grief for her mother that causes Catherine to sleep with Phil. She sleeps with him – a man she has no respect for – as a way of consuming and devouring life after facing so much illness and death. Enright gives us a nuanced and complex character and her motivations make us read urgently and hungrily whilst thinking, ‘Don’t sleep with him!’

I loved these stories before I knew too much about things like character motivation, verisimilitude, or weaving in stories within stories. I read them for pure pleasure because I was a fan of Enright’s novels. The more I‘ve learned, the more respect I have for her: she’s highly skilled at structure, at balancing past and present, at creating empathy and strong consistent voices, and she manages to be irreverent and poignant at the same time. I have much to learn and that’s why most of the time I sit with Taking Pictures squashed under my keyboard as I write, hoping for some infusion of greatness. These stories, even whilst dealing with bleak subject matter, manage to shine bright and original. As a reviewer in the New York Times commented: ‘Anne Enright’s fiction is jet dark — but how it glitters.’

~

Photo of Anne Enright by Eamonn McCabe

What a fine article! Reading this made me want to reread Anne Enright’s work, especially this collection, as well as reacquainting myself with Alex’s wonderful stories, and also to get back to story writing myself, from which I’ve strayed for too long.