photo crop © sez9, 2013

~

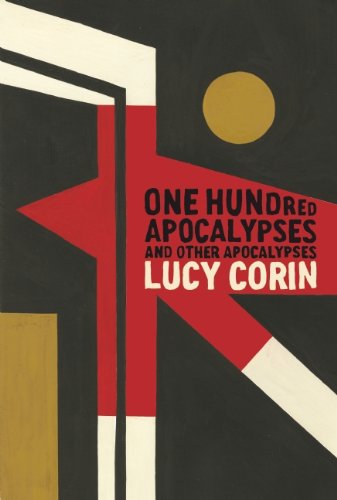

In this longlisted essay from the 2016 THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition, Sophia Kier-Byfield finds subjective interpretations of ‘apocalypse’ in Lucy Corin’s One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

~

Subjective Apocalypse in Lucy Corin’s

One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

by Sophia Kier-Byfield

Apocalypse. A word that tremors with meaning. Those four syllables throb with connotations of cataclysmic rupture, signifying incomprehensible destruction. The apocalypse is the world, as we know it, suddenly swept away.

In contemporary culture, the apocalypse is understood to be a single event of great magnitude, but the title of Lucy Corin’s 2013 collection, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses, suggests otherwise. It was the idea of apocalypse reworked that first drew me to the book: it allows for a diversion from the path of conventional apocalyptic or science fiction. These aren’t just stories about the collapse of our surroundings by natural disaster or alien invasion, but a thorough interrogation of what the word apocalypse can signify, as well as the creative energy that is knotted together with destruction.

The collection begins with three stories of conventional length, three stories that begin to invert the concept of an apocalypse from an objective, shared event of mass devastation to one that is personal and often more about momentous change than outright catastrophe. Apocalypse seems to be a two-sided coin for Corin, both calamitous event and, in the older understanding of the word, an uncovering or revelation (the word stems from the Greek apokalypsis). These stories map the macrocosm onto the microcosm and draw attention to the apocalyptic nature of daily, subjective experience.

One of Corin’s primary themes is the apocalyptic nature of growing up, an authorial decision that makes her texts tender and relatable. In ‘Madmen’, the protagonist gets her period for the first time, an event that means a trip to pick up the madman that will follow her into adulthood – each adolescent must go through this ritual. On contemplation, the apocalypse becomes a perfect metaphor for a moment of such significance: the female  body begins to undergo a seismic alteration, one that comes without warning, and marks the leap over a liminal boundary into womanhood. By marking this momentous change with the absurdity of picking a madman to care for – who may be male or female and must be chosen from a group of patients on display, like picking a pet at the pound – the reader realises the irreversible implications of this personal apocalypse. Both tangible and intangible ties to childhood innocence are severed forever: this girl will, from now on, begin to bear the burden of adulthood, with all of its social and bodily responsibilities and, some might say, madness.

body begins to undergo a seismic alteration, one that comes without warning, and marks the leap over a liminal boundary into womanhood. By marking this momentous change with the absurdity of picking a madman to care for – who may be male or female and must be chosen from a group of patients on display, like picking a pet at the pound – the reader realises the irreversible implications of this personal apocalypse. Both tangible and intangible ties to childhood innocence are severed forever: this girl will, from now on, begin to bear the burden of adulthood, with all of its social and bodily responsibilities and, some might say, madness.

Perhaps most poignant is the protagonist’s eager attitude towards this change. She speaks with confident maturity and witticism, jokingly referencing Lacan – ‘What’s that developmental stage called when you can finally do abstract thinking? Algebra? Just kidding’ – and taking pride in being the one ‘coming of age’. However, this only serves to highlight how we long for adulthood when we are children, but, once the apocalypse has happened, once we have attained that madness, we can’t go back. Like the apocalypse, growing up can’t be undone.

In ‘Godzilla Versus the Smog Monster’, a young boy named Patrick sees California burning on the television, but this disaster is not the story’s focal point. Instead, the reader witnesses an internal apocalypse. For instance, when taken to a cave by the older and intriguing Sara, the natural disaster going on just a few states away becomes irrelevant:

Again, he feels cozy. He can’t help it. California is burning, the first gobbling Eureka, all that marijuana up in smoke, people and animals are dying, the air is poisoned, the ocean is boiling, fishes make for Hawaii as fast as their flippers will carry them, rock tops exploding from sea cliffs like missiles, and he feels cozy, trying to figure out if maybe he’s attracted to Sara. He knows the one about how people have sex in the last moments before the end of the world, but it doesn’t feel like the end of the world.

The cataclysmic destruction of the physical world, amplified by Corin’s syntax and violent imagery, is rather a means for Patrick to start thinking about his body in a new way. The fact that the end of the world hasn’t quite arrived yet correlates with the fact that he’s ready to think about sex, but not to have it. Furthermore, the small fire that Sara builds for them to keep warm claims more importance than the raging fire in the distance. A conventional image of apocalypse becomes a catalyst for something far more intimate, perhaps even productive: sometimes it is only in moments of great uncertainty that people are brought together and can learn something about themselves from these encounters.

Towards the end of the story, Patrick sees his father ‘frightened, truly frightened, just for a moment’ over the fact that he can’t remember why he has Godzilla Versus the Smog Monster in his drawer. Corin’s apocalyptic diction emphasises the private significance of this event for Patrick, a boy who suddenly sees his father for who he really is:

There’s his father, lost, as if lost in a vast tundra. It’s the first time Patrick’s looked at this father and really seen himself there, in the past and the future at once. It shakes him. It makes a little dust rise.

In one fleeting moment, child and parent roles are reversed, as the former gains insight and the latter becomes stranded in the unknown. Patrick’s illusionary image of his father is shattered, and he too begins to make his way down a one-way path of growing up. We all experience these moments of major shift and anagnorisis in our life’s narrative. Therefore, by using the idea of apocalypse as a literary tool, Corin encourages us to reconsider their significance and how they have shaped us. These apocalypses are ‘pulsing with intimacy’, a symbol for the daily ontological crises that jolt us into viewing the world and ourselves differently.

Another noteworthy story is ‘Phone’, in which the colossal implications of the phrase I love you are contemplated. The story tells of a boy and girl engaging in a tender phone conversation, but the girl starts to feel ‘the earth turning to powder as he says the words’. Again, by juxtaposing the tropes of physical disaster with internal life, the emotions being felt by the characters are heightened and exaggerated. It is not necessarily that the ‘the end of the [whole] world has already happened’, but that the world, as these two entities experience it, is forever altered: it will never be the same. Apocalyptic imagery of chaos and dissipation appropriately exemplifies how the event of falling in love can turn the world of the individual upside down, smashing and splintering any sense of self:

…the telephone and the amplifier dot hillsides on opposite ends of the universe. The boy’s eyelashes flutter and spin like a blown dandelion. The girl’s fingernails sparkle in shards…

When reading the stories from the collection’s final section, I sensed something apocalyptic not only in the content, but also in the manner that these very short fictions, which might be called ‘microfictions’, are composed. The apocalyptic moment, with all its sudden, surging energy, is intrinsically tied to the great unknown: what comes after the moment is an epistemological blank, open to limitless interpretation. Similarly, Corin’s pieces of extreme brevity explode on to the page and then drop off into the abyss of the paper’s white, open and empty surface. For instance, ‘July Fourth’ simply reads as follows: ‘Got there and the ground was covered with bodies. Lay down with everyone and looked at the sky, bracing for explosions.’ This story inverts the fireworks and celebratory nature of American Independence Day into an event of destruction and death, but, despite this story having a generically cataclysmic event at its core, the focus remains on the subject caught up in the calamity. However, what strikes me as most compelling is how the following expanse of white page symbolises the aftermath of the textual explosion; the very properties of short fiction begin to become aligned with notions of apocalypse. The short story has always been associated with moments of narrative crisis, but it is a form in perpetual crisis itself. Just as an apocalyptic event renders something over before we are essentially finished with it, whether that be a relationship, an activity, or the world itself, these fictions are over before we have the chance to fully get to grips with them.

When reading the stories from the collection’s final section, I sensed something apocalyptic not only in the content, but also in the manner that these very short fictions, which might be called ‘microfictions’, are composed. The apocalyptic moment, with all its sudden, surging energy, is intrinsically tied to the great unknown: what comes after the moment is an epistemological blank, open to limitless interpretation. Similarly, Corin’s pieces of extreme brevity explode on to the page and then drop off into the abyss of the paper’s white, open and empty surface. For instance, ‘July Fourth’ simply reads as follows: ‘Got there and the ground was covered with bodies. Lay down with everyone and looked at the sky, bracing for explosions.’ This story inverts the fireworks and celebratory nature of American Independence Day into an event of destruction and death, but, despite this story having a generically cataclysmic event at its core, the focus remains on the subject caught up in the calamity. However, what strikes me as most compelling is how the following expanse of white page symbolises the aftermath of the textual explosion; the very properties of short fiction begin to become aligned with notions of apocalypse. The short story has always been associated with moments of narrative crisis, but it is a form in perpetual crisis itself. Just as an apocalyptic event renders something over before we are essentially finished with it, whether that be a relationship, an activity, or the world itself, these fictions are over before we have the chance to fully get to grips with them.

Indeed, in ‘Questions in Significantly Smaller Font’, the narrator asks: ‘What will the apocalypse mean for narrative?’ It is therefore important to give due attention to the fact that Corin chose the short story to explore ideas of apocalypse. The critic Frank Kermode suggests that the notion of apocalypse is a model through which to understand our very existence. He notes in The Sense of an Ending:

…already in St. Paul and St. John there is a tendency to conceive of the End as happening at every moment; this is the moment when the modern concept of crisis was born.

The short story’s preoccupation with crisis corresponds with the fact that, in Kermode’s words, ‘to live is to live in crisis – these ends bear down upon every important moment experienced by men in the middest’. In this respect, short fictions ‘can make sense of the here and now’: they reflect the way in which we are thrown into life, the shock of experience, the unobtainable nature of complete knowledge, and the fact that our endings will remain unknown, out of reach. Although Corin’s stories are but mere fragments, with no cohesion, definite sense of character, decisive action, or discernible context, it is this very fragmentation that makes them so vivid a portrayal of what it means to be human in an unstable world.

One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses, due to the very fact that it is a collection of short stories, reflects fundamental aspects of our disrupted human existence. But there is also something refreshing, even invigorating in the idea of apocalypse:

But tell you the truth, I kept asking for it. I was asking for the apocalypse. I was tired of the way things were going. I was looking forward to fresh everything. With the slate wiped clean, the whole world would be at my beck and call. Anything could be around the corner…

~ from ‘Fresh’

Sometimes the personal apocalypses that we endure, however intense and extreme they may be, can lead to something new: the destruction isn’t always absolute. When reading this collection, I certainly welcomed each apocalyptic ending, as it meant that a new story was about to begin.

~

Sophia Kier-Byfield gained her BA in English Literature from Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2013. After a year of working as a private tutor and travelling the world, she moved to Brighton to pursue a Masters in Modern and Contemporary Literature, Culture and Thought at the university of Sussex, completed with Distinction and department prize in 2015. Soon after, she decided to move to Aarhus to be close to her Danish family and explore this part of her identity. Sophia is currently working as an English Literature teacher at Aarhus University, cycling everywhere and trying to write more. She blogs at sophiakierbyfield.wordpress.com

Sophia Kier-Byfield gained her BA in English Literature from Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2013. After a year of working as a private tutor and travelling the world, she moved to Brighton to pursue a Masters in Modern and Contemporary Literature, Culture and Thought at the university of Sussex, completed with Distinction and department prize in 2015. Soon after, she decided to move to Aarhus to be close to her Danish family and explore this part of her identity. Sophia is currently working as an English Literature teacher at Aarhus University, cycling everywhere and trying to write more. She blogs at sophiakierbyfield.wordpress.com