(‘Modern Life‘ © Brett Davies, 2012)

‘UPSHOTS’: STUNTED, BUT STILL STANDING

by JULIA ANDERSON

The narrator of Joanna Campbell’s short story ‘Upshots’ is a young lad called Stan, and he begins by describing his father as ‘a man who righted woodlice when they were spinning on their backs’ and who ‘sprayed the loganberry leaves with sun-warmed water to soothe their rust blight.’ Stan says he ‘agreed with owt Da said on account of the way he spoke to me – as slow as cold gravy, knowing me brain-cogs are cock-eyed.’

Campbell’s writing is known for its wry humour, and ‘Upshots’ is no exception as she gives Stan an engagingly naïve voice and many incisively observational one-liners. Stan goes on to tell us how his father exchanged a currant loaf, made by Stan’s Mam, for a scabby cutting from Ma Bandle’s loganberry bush, and that Ma Bandle subsequently fed the loaf to her hogs. Stan says this exchange was fair for two reasons. Firstly, because the cutting, ‘grew to the same height as me – stunted, but still standing’ and secondly because ‘Mam’s currant loaf was well-known for bringing on a full day’s guts-ache.’

Children say the funniest yet most truthful things! I love lines like this popping up in serious stories – as they do in life. The ‘gut’s ache’ comment, reminds me of a sad day. After my father’s funeral, we tried to cut a fruit cake my mother had made and covered in royal icing. Unfortunately, the icing had set rock hard, rendering it impossible to slice. We tried every knife in the house – even the carving knife. We were both crying, saying how my father would’ve been able to cut the cake.

When we eventually re-joined our guests we were surprised to see my eleven-year-old son handing out pieces of the cake. I asked him what knife he’d used. “Grandad’s hacksaw from the shed,” he replied. “The one he used to cut through the radiator pipes. I figured if it can cut through metal, then it can deal with Nan’s icing.” Humour and tragedy often come hand-in-hand, in literature as in life. During stressful times that tiny release makes the intolerable just about tolerable.

Stan’s big sister Christine and his mother have just arrived home from hospital, and are sitting at the kitchen table ‘pretending nowt’s happened’ when Stan walks in. We soon learn that something has happened, though, as Stan tells us matter-of-factly: ‘We can’t pass the baby off as our Mam’s like every family with a sister fifteen years older than the youngest born, because Mam’s insides fell out when she last birthed.’ Christine, it seems, has ‘Done the Deed’ with a married man so the baby can’t come home, and now there are ‘black eye-cake smudges on the towel in the scullery.’

Ma Bandle has ten children of her own, but we learn that she also takes in unwanted babies – and now she has taken in Christine’s. To feed them all, she ‘wheels her pram around town, peddling tangled rolls of chicken-wire, encyclopaedias, the odd Indian-head hockey stick – anything she can swap for nosh.’

I feel deeply for these characters and their circumstances as I do for those in the real world to whom these events have happened. ‘Upshots’ epitomises that era when babies were put up for (official or unofficial) adoption if born to unmarried women. In its subtext, ‘Upshots’ is a piece of hard-hitting social realism.

Stan feels sorry for his heartbroken sister and for the baby who will now grow up without its mother. He also worries about the impoverished and filthy conditions the child has been taken into, knowing that ‘the Bandles live two to a plate, three to a bed, and keep a placid sow in a back room.’ Deciding to rescue the child, he gathers up his toy soldiers and dashes off to find Ma Bandle:

Along the riverbank, past the wasteland and over the bridge to the playing-field, round the back lanes and past the school that isn’t there anymore, and I’m fair out of breath. Me feet are soaked through on account of slipping into the river twice. One of the [toy soldiers] in me pocket jabs me leg with his rifle, but I’m too busy thinking to be bothered.

He’s out of breath when he spots Ma Bandle pushing her shabby pram with ‘Our Baby’ over the cobblestones on her way to Pig Club.’

The mention of Pig Club takes me back to my childhood. I loved hearing my grandparents’ war stories, especially about the Pig Club which was set up to supplement meat rations. On Mondays, it was Grandad’s turn to collect food scraps for the pigs from the houses on his street, but whenever he knocked on Mrs Johnson’s door, she took so long pretending to search for scraps that he’d give up and go away. Yet when the pigs were slaughtered, Mrs Johnson always rushed up the road to be first in the queue for the meat. I smile when Stan tells a similar story:

‘It’s well-known the Bandles don’t stump up many scraps, but they scramble to the front of the queue when it’s time to dish the bacon. The war might be over, but Pig Club’s not been given the chop and Mrs Bandle still expects her rashers.’

From his hiding place, Stan watches Ma Bandle leave the pram unattended as she goes into the Pig Club, but she returns too quickly, before he can make his move. When she makes a second trip, though, Stan seizes the moment, and moves ‘as quick as hell can grill an ounce of cheese.’ Quickly, he snatches the baby, wrapped up in its blanket, from amid the bric-a-brac in the pram and dashes towards home. As he arrives, though, he begins to worry that his Mam will be cross. He also feels ill:

In me head, I hear a hammer-clanging, drum-banging, bucket-clanking din. Me skin’s blistering like a flame-split tomato. I don’t know how one foot finds itself in front of the other, but somehow I’m in our back yard. The blanket’s the weight of a boulder.

Stan is clearly not well, but rather than dashing straight into the house with the baby, he wraps it safely in its blanket and sets it on a bench in the old air raid shelter at the bottom of the garden. Presumably he plans to soften his family up before presenting them with the child, but as he enters the kitchen to ‘a duet of screams’ and a ‘scattering of tea-cups’ he collapses. Stan is covered in the ‘rust-red blight’ and ‘swivelling black spots’ of German measles and is soon overcome by a delirious fever.

Three weeks later, Stan wakes up and at last, he’s well enough to sit up in bed to peel and eat an orange.

He listens to Christine talking to Mam. “Happen God knew we’d lost enough already.” Stan knows they are talking about Da who had helped Ma Bandle when her baby was blown from her arms in a bomb attack. The baby had no face after the blast. Stan’s father wasn’t the same again and one night he went out and drowned himself in the river. Now, too, we have an insight into why Ma Bandle feels such a strong need to rescue all those unwanted babies.

Finishing his orange, Stan overhears Christine ask Mam if she could have him back. Mam says no because of the shame. Stan realises she’s not talking about Da. Someone else is missing.

The baby.

Stan throws back the bed-sheets. ‘Orange peel scraps fly across the room…I stand up and fall over, not used to being upright.’ He stumbles out into the yard, trying to convince himself that, ‘It’ll be right fine though. Babies are as tough as old boots.’ The reader, however, knows differently, and this is a moment of true horror.

After four desperate attempts, Stan gets the shelter door open. ‘The sun has turned the bone-cool, fresh root smell into the reek of a roasting oven with summat forgotten inside.’ As Stan steps towards the small bundle on the bench, he tries to reassure himself about the smell: ‘Of course! The nappy will be full o’shite by now. That’ll be what’s kicking up the stink.’ But when Stan pulls the blanket back a little way the stench is worse – ‘maggoty-bad’.

In the semi-darkness of the shelter, he can just about make out, ‘a lumpy mottled pattern speckled over flesh that’s not as pink as it should be. More silvery-green.’ When Mam calls Stan back indoors he picks up the bundle which is, ‘heavy, but quite, quite still.’

We are often told that the job of a writer is to disturb the comfortable, and the scene in Stan’s shelter certainly filled me with horror. Rather than giving us such a painfully clear image of Christine’s baby, though, I wished Campbell had left it to the reader’s imagination as William Trevor does in his short story, ‘Miss Smith’. In it, James, a young pupil of the nasty Miss Smith has abducted his teacher’s toddler son. A search ensues but the child isn’t found. Days later, James turns up asking Miss Smith if she’d like to see her baby. Stunned, she follows James: ‘over the canal bridge and across the warm, ripe meadows.’ And there, Trevor leaves it up to the reader whether they imagine – or don’t – what the mother will find when ‘they arrived at the horror’ and ‘the horror was complete.’

Just as Stan is about to enter the house with the bundle in his arms and tears streaming down his face he hears Christine telling their mother about Ma Bandle. A few weeks back, she had been kicked out of Pig Club for stealing a ham hock. Ma Bandle admitted taking the ham but was so ashamed by what she’d done that she had returned to her pram, prepared ‘to hand over half her worldly goods in fair exchange’ only to find that the ham was gone.

Oh, the relief I feel as it dawns on me what Stan had really taken from the pram. Thank you, Joanna Campbell for your clever plot twist and for knowing that what comes after disturbing the comfortable – is – comforting the disturbed.

And so, ‘Upshots’ ends as it began – with loganberries – grown from the scabby cutting that Ma Bandle gave to Da. Plenty of berries for Stan’s Mam to make pies. Although Stan wants to tell Christine and Mam he’d like, ‘…our small lad back’, he accepts some things aren’t meant to be:

He’ll be staring up at Ma Bandle’s shovel-shaped leaves, watching the sky, waiting for her to lift him up and take him inside. But I keep that thought to meself, take the trug and go back with Mam and our Christine to gather fruit.

~

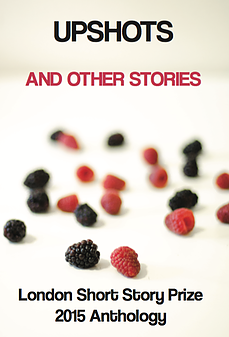

‘Upshots’ was the winner of the 2015 London Short Story Prize.

~

Julia Anderson writes short stories, flash fiction, poetry, essays and features. She’s been published in the Words with Jam anthology and in a range of magazines, and placed first, second or third in several competitions and also shortlisted or longlisted in quite a few more. Currently, she’s set herself a challenge to write mainly happy or humorous fiction instead of her usual topics about sad, bad, or mad characters. For this, she feels sure that many competition judges and editors will be grateful and that she’ll feel more cheerful herself. Following Ray Bradbury’s advice to all writers, she reads one poem, one essay, and one short story every day. (As well as all the other books and magazines she has on the go, which are of course, scattered all around the house.)