('Fail at writing' © Ilena Gecan, 2008)

*

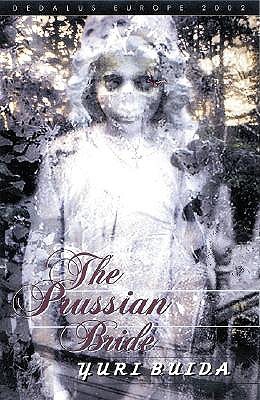

In this essay, one of two runners-up in the 2017 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Cathy Sweeney finds a ‘tender meditation on the human condition’ in Yuri Buida’s short story collection The Prussian Bride, and the story ‘Sinbad the Sailor’.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘A powerful and beautiful piece. Its insights are luminous. Its combination of playfulness, discernment and sharp honesty is exquisite. I didn’t know Buida’s work before, and now I long to read it. This piece reminds me of what a privilege it is to hear from great short story readers at THRESHOLDS. It’s an absolute gift of an essay.’

‘A wonderful introduction to a writer I didn’t know, and who I’m now eager to read. There’s great sweep and depth in the writing, and a lovely balance between enthusiasm and analysis.’

‘Buida sounds a fascinating writer – I thought this was brilliant!’

~

*

Cathy Sweeney is a writer living in Dublin, Ireland. She has published short stories and essays in The Stinging Fly, Southword, The Dublin Review, Icarus, Meridian, and in the anthology Young Irelanders, published by New Island Press 2015.

*

*

~

STORYTELLER, LIAR, DREAMER

by CATHY SWEENEY

In his 1998 collection of short stories, The Prussian Bride, Yuri Buida includes two loosely autobiographical vignettes, one at the start, Instead of a Preface, and one at the end, Instead of an Afterword. In the latter, he humorously recounts how, when his first article appeared in a Polish newspaper, the editor did not believe that Buida was his real name, since in many parts of Poland buida means ‘lie, fantasy, fairy tale’, and at the same time ‘story-teller, liar, dreamer’.

It is a perfect anecdote. Yuri Buida, born one year after Stalin’s death, is the monster child of Stalin’s vision of what a writer should be. In 1932, the Central Committee of the Communist Party disbanded all existing literary and artistic groups and replaced them with the Artists Union of the USSR. From that point on, it decreed, the creative artist would be ‘realistic, optimistic and heroic’. It is as though Buida, stamped at birth as the antagonist of cultural orthodoxy, was destined to live up to his own name.

Born in Znamensk, in the Kalingrad Region of Russia, Buida was seven before he discovered that the town used to be called Wehlau. With the defeat of Nazi Germany, in 1945, the territory had been annexed by Stalin and all German citizens expelled. Buida’s mother was part of the first group of settlers to arrive in the region from Central Russia. Her train ticket bore the name of her destination, the town of Wehlau, but, as the train pulled in to the station, workmen were busy removing it from the signs. All the stories in Buida’s collection The Prussian Bride are set in Znamensk. They depict the half-real, half-fantastical lives of the local people, lived  out in this ancient tabula rasa. In the vignette at the start of the collection, Buida wrote: ‘The writer, the dreamer, lives not in Znamensk or Wehlau, but in both places at once, in Russia, in Europe, in the world.’ How true, and also how literally true; after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the entire Kalingrad region was cut off from the rest of Russia by other countries.

out in this ancient tabula rasa. In the vignette at the start of the collection, Buida wrote: ‘The writer, the dreamer, lives not in Znamensk or Wehlau, but in both places at once, in Russia, in Europe, in the world.’ How true, and also how literally true; after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the entire Kalingrad region was cut off from the rest of Russia by other countries.

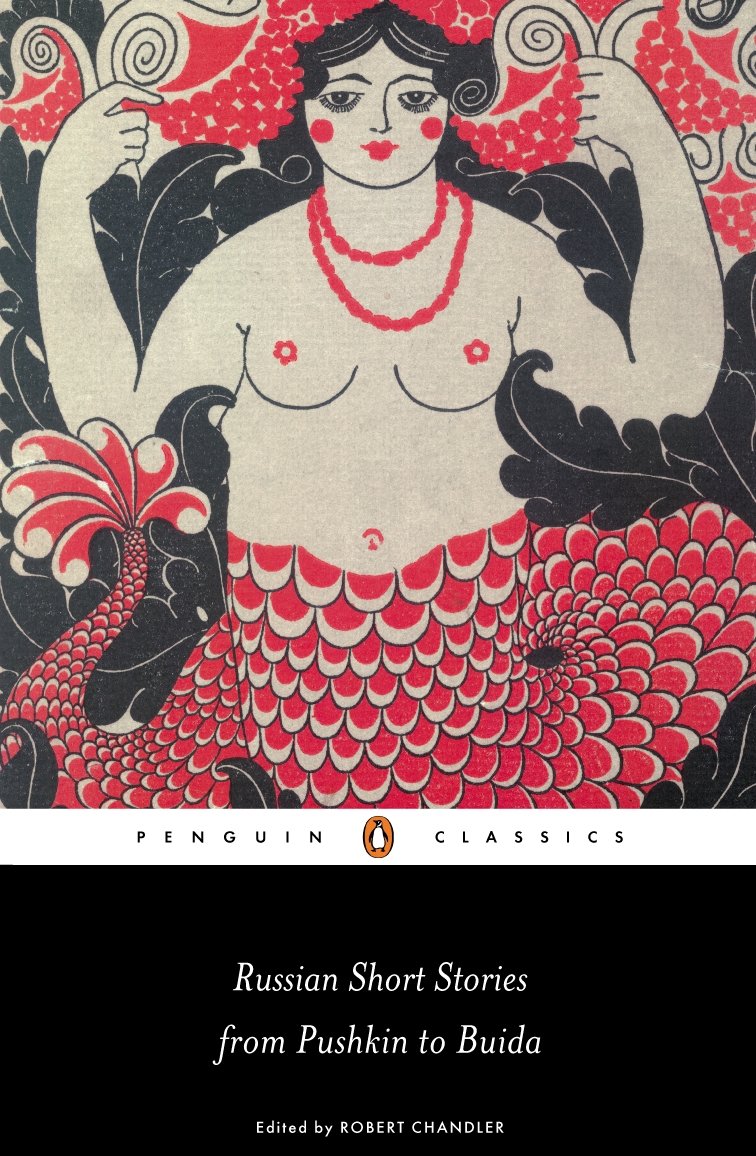

I first encountered Yuri Buida in an anthology: Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida. His short story ‘Sinbad the Sailor’, translated by Oliver Ready, is the last story in that volume. A poor old woman, dying in hospital, sends for the doctor who has treated her all her life. When he arrives, she gives him a folded scrap of paper and the key to her house, and asks him to go there and burn this scrap along with the others he will find there. The doctor, taking the local policeman with him, agrees to her strange request. In the old woman’s house they find an enormous pile of paper. Like the scrap the old woman gave him, they all have the same words written on them, a love poem by Alexander Pushkin, followed by a date. Stunned, the doctor spends the night putting the 18,252 scraps of paper in chronological order, before burning them. This is not a spoiler, although, yes, I have given the plot away. It is not a spoiler because the ‘plot’ is the least important aspect of a Buida story; it is other elements that make this a story that gets under your skin and stay there. To say that the plot encapsulated the story would be the equivalent of saying Hamlet is a story about a prince who wishes to take revenge on his uncle for killing his father – and does – it just takes him a really long time!

So, if plot is the least important thing in a Buida short story, what are the other elements that make ‘Sinbad the Sailor’ great? Let’s start with this: many writers distrust stories. This may seem odd since they are compelled to spend their lives telling them, but such is human nature. I am thinking of writers such as Kafka and Borges and Pirandello and Beckett. And Yuri Buida. They do not consider stories to be the source of truth because they know that truth is a tricky thing, and not something that can easily be contained between ‘once upon a time’ and ‘the end’, like meat between two pieces of bread. If there is something akin to ‘truth’ in a story, it is like the truth that comes from dreams: you understand it, but if you try to analyse it, it runs through your hands like sand. The first stories of the world – myth, legend, fairy tale – are like this. It is only deluded and dishonest societies, such as the Soviet Union or our own dying western liberal democracies, that develop a taste for stories that are ‘realistic, optimistic and heroic’. The Russian writer and critic, Victor Shklovsky, put it like this:

The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make stone stony.

The Prussian Bride is a comedic, yet peculiarly tender meditation, on the human condition in all its madness. It is peopled by characters who castrate themselves to prove their love, who kill their neighbours, who bury empty coffins, who boil their feet in Vaseline so that they fit into porcelain shoes. Characters who are both tough enough to survive the hardships of Communism and human enough be transformed by love, to  meditate on time, to ponder the mystery of beauty. Many of the stories explore the tenuous bonds that hold people together: mismatched couples, cobbled-together families, communities made up of eccentrics and misfits. They are an odd mixture of the gothic and the poetic, and they remind me of a writer from a different time and world: Flannery O’Connor, the great Southern American writer of the mid-twentieth century. Like O’Connor, Buida is not an airy writer; he is earthy, his places are real, his people are real; his understanding of the experience of life is all the more real for being fantastic. O’Connor’s great observation on fiction can be applied directly to the short stories of Yuri Buida: ‘The truth is not distorted here, but rather a distortion is used to get at truth.’

meditate on time, to ponder the mystery of beauty. Many of the stories explore the tenuous bonds that hold people together: mismatched couples, cobbled-together families, communities made up of eccentrics and misfits. They are an odd mixture of the gothic and the poetic, and they remind me of a writer from a different time and world: Flannery O’Connor, the great Southern American writer of the mid-twentieth century. Like O’Connor, Buida is not an airy writer; he is earthy, his places are real, his people are real; his understanding of the experience of life is all the more real for being fantastic. O’Connor’s great observation on fiction can be applied directly to the short stories of Yuri Buida: ‘The truth is not distorted here, but rather a distortion is used to get at truth.’

‘Sinbad the Sailor’, as with many of Buida’s stories, is a short short story, just over four pages. Economy is the hallmark of this writer’s work. This, however, does not preclude an extraordinary eye for detail when it is deemed necessary. Early in the story the doctor gazes ‘at the midges circling a pale streetlamp atop a wooden post turned green by the damp’. Buida also favours specific proper names. The three characters in this story are Katerina Ivanovna Momotova, Doctor Sheberstov, and Lyosha Leontyev. Dark humour abounds. The reader is informed that Katerina Ivanovna is ‘famous throughout the town for her exemplarily unsuccessful life’. She has suffered a litany of personal disasters including losing ‘half a leg after getting run over by a train’ and the death of her eldest son by drowning. Throughout this life of unrelenting hardship and misfortune, she works: first as a washerwoman, then as a shepherdess, and finally by collecting empty bottles in the ditches and woods out of town. It is this last activity that earns her the nickname ‘Sinbad the Sailor’. All this tragedy has befallen someone who obviously possessed a caring nature – two of her four children were orphans from the children’s home.

Katerina Ivanovna, this one-legged old woman who slurps up vodka poured onto bread, wrote out, every single day, without punctuation or correct spelling, a love poem by Alexander Pushkin:

I loved you. Even now, perhaps, love’s embers

Within my heart are not extinguished quite.

But let me not disturb you with remembrance

Or cause you any sadness, any fright.

I loved you hopelessly, could not speak clearly,

Shyness and jealousy were ceaseless pain,

Loved you as tenderly and as sincerely

As God grant you may yet be loved again.

“What’s it all about? Eh?” asks the policeman when the two men find the ‘mountain of paper’. “So who do you think invented the soul, the devil?” retorts the doctor angrily. Buida resists any attempt to explain behaviour: this is not consumer fiction; the reader trained to expect the holy triad of arousal/manipulation/fulfilment will be bitterly disappointed. Katerina Ivanovna may be a pitiful old woman, but as with many of Buida’s lonely, broken, outcast characters, there beats within her a heart – and the human heart is full of unknowable depths,  unknowable to others and even to ourselves, and Buida understands that. In her lecture ‘On Classical Pornography’, Susan Sontag takes issue with realism, which, she maintains, can create a ‘too easy empathy’, a ‘false intimacy’ with the reader, an immediate reassuring access to a text that leaves out mystery, transcendence, otherness, and what D. H. Lawrence called the ‘it’ – that which escapes words.

unknowable to others and even to ourselves, and Buida understands that. In her lecture ‘On Classical Pornography’, Susan Sontag takes issue with realism, which, she maintains, can create a ‘too easy empathy’, a ‘false intimacy’ with the reader, an immediate reassuring access to a text that leaves out mystery, transcendence, otherness, and what D. H. Lawrence called the ‘it’ – that which escapes words.

Yuri Buida, as I have said, is no airy writer. His protagonist, Katerina Ivanovna, lived out her life in a real world. She put the date at the bottom of every scrap of paper and very occasionally added a few words – March 5, 1953, ‘Stalin dead’, or April 19, 1960, ‘Fyodor Fyodorovich [her husband] died’. The political world and the personal world shape existence; one is not isolated from the other, although you wouldn’t know this from reading a great deal of contemporary fiction in which characters seem to live in bell jars, hermetically sealed from the outside world.

At the end of the story, just before dawn, the two men, the doctor and the policeman, feeling uneasy, start burning the paper. The doctor keeps one scrap, although he doesn’t know why:

Perhaps just because, for the very first time, the old woman hadn’t written the date at the bottom, as though she’d understood that time is powerless not only over the eternity of poetry, but even over the eternity of our wretched life…

What a last sentence. It leaves the reader stumbling blindly towards a truth that can never be fully comprehended. And then there is more. But it’s not on the page: it is in your head – that great tolling silence that a story such as ‘Sinbad the Sailor’ leaves in its wake. Buida is that rare writer who is afraid neither of profound philosophical questions or intense emotions.

So, to return to the old chestnut: what makes a great short story? Obviously, despite my efforts at analysis, the answer is subjective; I read Buida because I don’t have time for narrative arcs (exposition, conflict, climax, resolution), or epiphany, or characters who work things out and find closure; I don’t have time for stories that mimic a version of life in which people get what they deserve. I have a stronger appetite. A saccharine aftertaste is no good to me; like someone suffering from pica, I crave the taste of dirt or petrol or metal. A taste that I can never, after reading a story, not taste. But, most likely, there is only one quality that I think we can all agree on, and that is the power of a story to entice you back to read it again, and again, and again, creating, over a lifetime, a relationship between you and it, in which, as you change, so the story changes too, reading you, in the end, as much as you read it. ‘Sinbad the Sailor’ is such a story. And so, in a time when the words ‘realistic, optimistic and heroic’ can so easily be applied to so much of what passes for fiction, a reader could do worse than to pick up a story by Yuri Buida, and in so doing be reminded of what all stories – from political manifestoes to watercooler gossip, personal memoir to potboiler novels – actually are: ‘lies, fantasy, fairy tale’.

One thought on “storyteller, liar, dreamer”

Comments are closed.