photo crop © Pradeep Kumbhashi, 2010

*

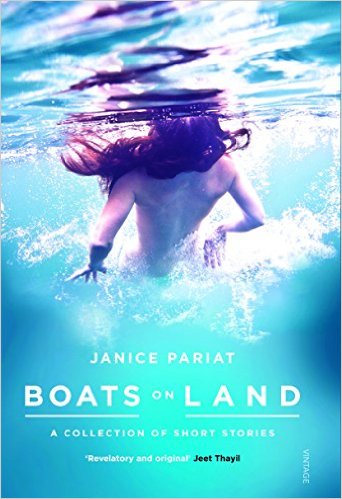

In this essay, shortlisted for the 2016 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Susmita Bhattacharya finds folklore, magic-realism and a celebration of the natural beauty of north-eastern India in Janice Pariat’s collection Boats on Land.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘The author draws upon their own autobiography in a vivid and moving way, to show us the unexpected reality and relevance of magic and folklore’; ‘an enjoyable experience, being taken into another culture by an intelligent and enthusiastic guide’; ‘a gentle and personal reflection … full of sensual imagery which transports the reader to another world’.

~

Susmita Bhattacharya‘s debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian), was published in March 2015. Her short stories have appeared in several literary journals in the UK and internationally, such as The Bangalore Review, Wasafiri, Litro, Riptide, Eleven Eleven, Tears in the Fence and have been broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

*

~

Boats on Land: Stories of the Magical and the Real

by Susmita Bhattacharya

My childhood summers were spent in my grandmother’s house, in a small town in Jharkhand, India, far away from the urban metropolis I called home. It was a very different way of life there, rustic and carefree. One of the highlights was the power cuts, annoying to the locals but so new and exciting to us. Often, when visiting a family friend, we’d be plunged into darkness, and that could mean only one thing: running to find Khokon kaka, the caretaker, who transformed into a storyteller. We would gather in the courtyard, oblivious to the mosquitoes drilling into our skin through our clothes, shivering in anticipation as he brought to life ghosts and witches, headless corpses and the resident spirit: a woman holding a lantern, floating above the pond at the base of the very steps we’d be sitting on.

Janice Pariat’s Boats on Land: A Collection of Short Stories is an amalgamation of folklore, magic-realism and a celebration of the natural beauty of north-eastern India, which has not had much exposure to the rest of the country or the world. The Khasis, the indigenous people of Meghalaya, one of the seven states that make up north-east India, had an oral language until the British missionaries arrived in the mid 1800s, and introduced the alphabet along with Christianity.

We, who had no letters with which to etch our history, have married our words to music, to mantras, that we repeat until lines grow old and wither and fade away. Until they are forgotten and there is silence […]

The memsahib says she would like to teach me to read and write, with something called ‘alphabet’ that her husband has invented for our language. I explained to her that we have no need for these things – books, and letters, and writing – and everything we know about the world is in the sound of our words, ki ktien. It has the power to do good.

~ from ‘A Waterfall of Horses’

In an interview with New Asian Writing, Pariat says:

Boats on Land is my modest homage to the act of storytelling. Its orality and theatricality. Storytelling as performance and transformation. As archive and reservoir of history. As gossip and rumour and scandal. And as the fictions of our everyday lives. I’ve carried these stories around for years – faithfully filched from fireside evenings and familial gatherings, from folktales I heard as a child.

And so enter the magic spells, charms and curses, doctors who practise medicine and witchcraft, prophecies and hidden desires that merge into the daily lives of the people and appear as one seamless way of life. These are stories of ordinary people: British soldiers and missionaries, memsahibs, doctors, lovelorn youngsters, the ill and the dead, but Pariat sees them through a kaleidoscope, colouring their stories with the magical qualities of folklore and myth. The stories appear chronologically, with the first story, ‘A Waterfall of Horses’, set in the 1850s, in a village in Meghalaya, and the last, ‘An Aerial View’, in more recent times in Greenwich, London, encompassing the changes in socio-political upheavals and altering landscapes along the way.

And so enter the magic spells, charms and curses, doctors who practise medicine and witchcraft, prophecies and hidden desires that merge into the daily lives of the people and appear as one seamless way of life. These are stories of ordinary people: British soldiers and missionaries, memsahibs, doctors, lovelorn youngsters, the ill and the dead, but Pariat sees them through a kaleidoscope, colouring their stories with the magical qualities of folklore and myth. The stories appear chronologically, with the first story, ‘A Waterfall of Horses’, set in the 1850s, in a village in Meghalaya, and the last, ‘An Aerial View’, in more recent times in Greenwich, London, encompassing the changes in socio-political upheavals and altering landscapes along the way.

In my mind, the stories appear to be created in a large cauldron, where Pariat uses the basic ingredients for short fiction – characterisation, setting, mood, dialogue – and then adds those extra flavourings of the magical, the folkloric and the mythical, to create a fantastic platter of literary hors-d’oeuvres. For me, growing up in India, folktales have been an intrinsic part of my cultural grounding and education. These stories weren’t just meant to entertain, they also dispensed wisdom and moral values that we should aspire to learn and follow by example. Different regions of India often have the same folktale, draped in local colour and language, and delightful vernacular; we can all relate to the themes because these tales are familiar, even though they are told differently.

Pariat uses the local landscape, weather and dialect to create a surreal atmosphere and nostalgia in this collection. Her descriptions of the rivers and forests, peopled with fairies and spirits in trees, and the constant moody rain, do not reinforce the stereotypes used to describe the mysterious Northeast, but create a world of deeper meaning, showing us her personal feelings and her love for her land.

I trampled on, aiming for a distant hillock which had a trickling stream curled around its base. To my far left, bordering the [golf] course stood a row of thatch shacks hazily covered in light rising mist. A few children, almost naked, ran after each other laughing and screaming. Further away, a boy was herding cows and their lowing, along with the chirrup of roosting birds, filled the air. On winter evenings, Assam dissolved into a carefree watercolour of flat shimmering horizons and low, languorous clouds. So different from Shillong where the skyline loomed with pine-shielded hills.

She often takes real life incidents, or characters and turns them into a fictional piece. Many of her stories are inhabited by characters inspired by her grandfather, as in ‘Sky Graves’. Or her great-grandfather in the ‘Dream of the Golden Mahseer’. Her stories move in and out of fact, reality and myth, as she points out in an interview with Asiasociety.org:

…the interweaving of the magical and mundane, of folk tales and historical fact, of the mythic and quotidian, is a reflection of this intricate layering of reality.

She uses words from the regional dialect generously in these stories, to recreate a direct connection with people and themes. Even though I do not understand the words, and she does not translate them most of the time, it doesn’t take away from the story, but rather embeds it more firmly in its roots.

Devdutt Pattanaik, a well-known mythologist and commentator on ancient Indian folklore asks the pressing questions in ‘Of Aubergine and Okra’, a blog post: Who is the story’s audience? Does the storyteller narrate the story to suit the audience’s understanding or for her own satisfaction? Does the storyteller stick to the truth or change the words, the stories for the audience’s approval? He goes on to say:

In ancient Indian storytelling tradition, one is gently made vigilant about the gap between the words of the storyteller (sauti), the story (katha) and the audience (shaunak). Would the character in the story actually say what the storyteller claims he did? Would the audience understand what is exactly being told by the character in the story? Is the story being changed to make it more accessible? All these points impact the story that eventually gets transmitted.

Pariat stays true to the authenticity of the local language and texture in her storytelling, and invites us to step into this world and understand and appreciate the stories, complete with the earthiness and truthfulness that is conveyed.

The connection of ‘fairy tales’, or ‘folklore’, to illness, mental or physical, and old age, stood out to me, particularly, as a guiding theme. In ‘The Discovery of Flight’, a man’s disappearance, for example, is foretold by a series of premonitions:

Someone had heard the rooster crow five times that morning. The moon the evening before, was ringed twice. And the symbols in everyone’s dreams – from dead cats, and dismembered limbs to fallen trees and a flock of birds taking flight – became sure signs that Ezra would walk out of his uncle’s house and disappear.

At other times, the melancholy is portioned out bit by bit in a story, revealed to us in several layers, without actually spelling it out. The title story, ‘Boats on Land’, is written as a second-person narrative, told in the voice of a sixteen-year-old girl who spends her summer holidays in a tea estate in Assam with her parents and their friends. There she meets the nineteen-year-old daughter of her parents’ friends. The bungalow holds an air of mystery, hidden behind high walls, ‘gated and guarded’ from outsiders.

It was far removed from the countryside’s lush wildness – ponds overflowing with hyacinth, thick clusters of swaying bamboo, and gulmohar that burst into a rage of orange and yellow blossoms.

But within this beautiful setting, is a troubled young girl, unable to express how her mother’s mental illness has affected her, making her dive deep into depression. She confides to the narrator:

[My mother] didn’t want a decisive relinquishment – a once-and-for-all hanging, or fatal leap or a bullet through the brain. She only had the inexplicable urge to extinguish herself and flicker back like a trick candle. She wanted to, for instant, to throw herself in the path of oncoming buses, or fall down a steep flight of stairs, or constantly push the number of sleeping pills she could take, where she didn’t have to be rushed to hospital and stomach-pumped…

The juxtaposition of the wild, natural beauty of a river that brings solace with the untamed, troubled mind of this young girl showcases how extreme her behaviour is and why. As Marina Warner says in Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale, even though a fairy tale is peopled with princes and queens, castles and palaces, ‘through the gold and glitter, the depth of the scene is filled with vivid and familiar circumstances, as the fantastic faculties engage with the world of experience’.

The juxtaposition of the wild, natural beauty of a river that brings solace with the untamed, troubled mind of this young girl showcases how extreme her behaviour is and why. As Marina Warner says in Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale, even though a fairy tale is peopled with princes and queens, castles and palaces, ‘through the gold and glitter, the depth of the scene is filled with vivid and familiar circumstances, as the fantastic faculties engage with the world of experience’.

In the story ‘At Kut Madan’, the local missionary cares for his young English niece, Lucy, who is suffering from an unknown illness. She is exhausted, losing her appetite and weight, and yet there is nothing physiologically wrong with her. The doctor is called, not for his medical knowledge, but for his other services as a shaman. She is ‘kem ksuid’ – possessed by spirits – ‘forced to languish and waste away’. She describes blinding headaches, a flash of light searing through her brain, and, in that instant, sees a ‘dazzling fire bird’ that ‘comes crashing to the earth, like a star that’s burst into a million flames’.

No one takes her mutterings seriously, saying her visions are all down to the traumatic experience of the Blitz in London, where her parents died, and she is sent to her uncle in Sohra. She finally recovers and returns to England and is forgotten, until, one day, a blinding light falls from the sky into the forest. The doctor remembers Lucy’s dreams, and there it is: a Dakota plane has crashed into the hillside, killing all the passengers inside. And it looks just like the firebird that had consumed Lucy’s mind when she was ill.

Are fairy tales and folklore a front to explain the alternate functioning of the human mind? Are they an alternative explanation of mental and physical conditions that are hard to accept in reality? Pariat’s stories embrace these people, their pain and their struggles to deal with the realities of life.

Local legends and folklore also come alive in the stories: waterfalls are transformed into white horses leaping from the drop; men shape-shift into animals, or are able to predict winning lottery numbers in their dreams, or slip away into the rivers with the water fairies. These stories provide a deeper understanding of the culture and mental landscape of the people living in that area. Folklorist Sara Graca da Silva says that folktales are ‘excellent case studies for cross-cultural comparisons and studies on human behaviour’ and Pariat accomplishes this genre with flair.

With these stories, she transported me back to a place where tales were told in candlelight, where grandmothers, uncles, aunts, cousins sat around the dining table, the aroma of mutton curry mingling with the smell of melting wax and polished wood. And the stories. Always the stories shared on those dark nights, of ghosts and ghouls, past tales, and eccentric family members. They continue to thrive in my versions, restyled and with fresh garnishing, told to my daughters at the dining table in grey and damp England.