photo © Chris Keating, 2006

by Lela Tredwell

On the exhausting list of things an old boyfriend and I used to quarrel about, nestled between ‘giving to charity’ and ‘pre-determined selective sterilisation’, is the meaning of the word special. “Are we talking ‘my special’ or ‘your special’?” he’d say, rather petulantly…

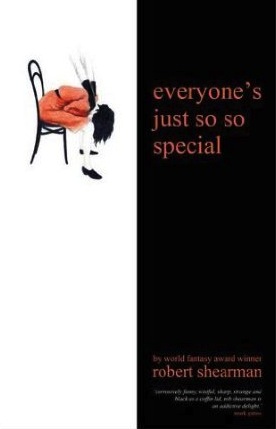

Thank heavens, there is no longer a need for such debate. Not now that I’ve discovered souls like Robert Shearman. His writing is as good as you’re going to get to a dictionary definition: ‘better, greater and otherwise different from what is usual’. And it’s for his third collection of short stories, in particular, that he is just so, so special, to me.

Shearman, never one to make things easy for himself, has assembled a collection with a startling difference. Amongst the stimulating mix of stories in Everyone’s Just So So Special are woven the parts of another narrative, in which Shearman squeezes two thousand years of human history, from 1AD. This small-print-story may require reading glasses, but is well worth the investment as it transfuses, from its historically inspired vein, musings that bleed out into the other stories.

It is masterfully done, with ‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’ entangling the other stories within its circulatory system, the web of history itself… or, at the least, one man’s version of it. In an exercise book, an enthusiast compiles a list of historical deeds, acts, he believes, of mediocre people aspiring to be more than they are – aspiring to be special. The man considers it his duty to expose these phonies, so he lists the events, puncturing them sporadically with his own reflective asides.

Everyone just wants to pretend they’re important, everyone wants to be so so special. Killing each other and blinding each other and buying giant cannons to blow each other up, like demented children.

The record reads like a roll call of the dead, the dying and the maimed. At the heart of it all are families – squabbling, feuding and fating each other to often grisly ends. While monarchs get younger and younger during the 1400s (some claiming the throne as young as ten years, six years, nine months old), the man recording events in his exercise book is equally usurped when his favourite childhood history book, The Wise Old Owl’s Book of Famous People, proves ‘a bit too basic’ for his three-year-old daughter, Annie. This thread in ‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’ is echoed in ‘The Big Boy’s Big Box of Tricks’, in which a magician is upstaged by a child with a ghastly new trick.

The record reads like a roll call of the dead, the dying and the maimed. At the heart of it all are families – squabbling, feuding and fating each other to often grisly ends. While monarchs get younger and younger during the 1400s (some claiming the throne as young as ten years, six years, nine months old), the man recording events in his exercise book is equally usurped when his favourite childhood history book, The Wise Old Owl’s Book of Famous People, proves ‘a bit too basic’ for his three-year-old daughter, Annie. This thread in ‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’ is echoed in ‘The Big Boy’s Big Box of Tricks’, in which a magician is upstaged by a child with a ghastly new trick.

There was no blood. And he chewed further as if he were enjoying the meal so much, as if his own flesh was the tastiest treat ever, oh, he couldn’t get enough of it! And he chewed further, right to the bottom of the chin, to areas his mouth could never have reached, surely?

Tommy’s act catches on with his peers and soon they’re all doing it, effectively silencing the voices of the next generation. Surely, this is story-telling at its most terrifying. And it all helps to build the tension when reading ‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’ – we start to fear for Annie; will she be silenced at the hands of this man who seems so taken with making marks? But we are also conflicted. She is special, is she not? Should we instead be as fearful for her father?

Throughout, we feel the desire and danger that being special holds. Many of the stories in the collection have the power to bruise, to give you an almighty blood blister, as is the case with ‘Times Table’, which I would not recommend reading if you’re home alone (with an attic). A girl is abandoned by her parents due to her special condition. Each year on her birthday she sheds her old skin for a new one. She keeps the discarded shells in the roof, where the collection grows, until one day she hears a knocking on the trap door… Someone, or something, wants to be let out. I still have a vivid feeling of how I felt when I had just finished reading this story: a sublime kind of shell-shock.

The themes of abandonment and loss feature strongly in Everyone’s Just So So Special. In ‘This Far, and No Further’ a mother loses her daughter and then misplaces almost all memory of her too, saved only by a Post-it. The mother must, quite literally, stop the march of time to find her daughter. Socialites in London stand around, waiting for Big Ben to strike in the New Year, to no avail.

In many of the stories there is the sense of time parading on, ‘history’s onward roll’ (‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’). To compliment this, Shearman has a very special skill for not allowing a story to stop short, refusing to let us off the ride until we’ve experienced every turn.

When you look at it, all history is just a collection of memories, and then interpretations and reinterpretations of memories by people who weren’t alive to remember the events in the first place.

~ ‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’

In ‘Restoration’, a devilish, God-like curator dictates that massive pieces of art that represent each year in human history should be first mutilated, then destroyed. Here, Shearman explores what happens when we start to lose our memory, when it’s entirely gone and there are no canvases, Post-its, or pieces of paper to remind us what once we meant.

In ‘Restoration’, a devilish, God-like curator dictates that massive pieces of art that represent each year in human history should be first mutilated, then destroyed. Here, Shearman explores what happens when we start to lose our memory, when it’s entirely gone and there are no canvases, Post-its, or pieces of paper to remind us what once we meant.

In this part of the interlacing ‘Everyone’s Just So So Special’ web, we are reminded of the 17th century peasants who are lost to history. These lost souls pass into ‘Acronyms’, in which James is employed to erase people by the influence of his mediocrity. He only needs to look at some people and they are so mediocre already, they vanish on the spot.

Everyone’s just so so special, and it means that “special” means nothing any more. So. We have to use your mediocrity to make others more mediocre too. We need to make the special people stand out.

Shearman’s collection needs no such aid to stand out. It shows us the possibility of collecting stories, entangling them, trusting that they will speak for themselves and for all the other stories around them. I would highly recommend it to you. It will give you a mortal motion sickness, a blood rush high, an awe-inspired aching of the creative muscles…

Just make sure you have a magnifying glass at hand for the small print, because, believe me, you wouldn’t want to miss a word. Every one being just as so, so special as the last.