photo by Francesco Ungaro

by Mike Smith

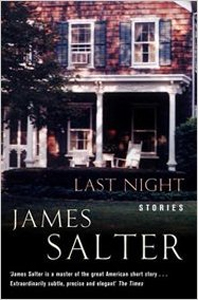

Reading James Salter’s ten-story collection Last Night, I got the sense that here was a writer, like D.H.Lawrence, having several goes at exploring a similar theme. In particular, Salter’s stories ‘Palm Court’ and ‘Bangkok’ seemed to be something like mirror images of each other.

In both stories, male protagonists are re-visited by their romantic and sexual pasts. In ‘Palm Court’, Arthur gets a phone call from an old flame, with whom he subsequently meets up. In ‘Bangkok’, Hollis receives a visit from an ex-lover. In both cases the women are offering a renewal of the lost relationship. In both cases the male protagonist looks back on the previous relationship in an idealised way. In their different ways, they both tell us that those had been the best days of their lives.

He only knew that he was happy, happier than he had ever been…

~ Arthur, in ‘Palm Court’

With you I felt I had everything in life.

~ Hollis, in ‘Bangkok’

In the case of each narrator, those days had been brought to an untimely end. In the first story, Arthur has allowed Noreen to slip away from him: ‘she admitted meeting someone else’ and, when ‘she was really giving him one last chance’, Arthur funks it, as he will do again later in the story.

The trajectories of both narratives, although not quite parallel, run close enough for the reader to be aware of the similarities between them. It is as if the author has been testing the same theory under alternative conditions. The similarities in the circumstances of the narrators of the stories are striking, but so are the differences. In ‘Palm Court’, Arthur is not married, while in ‘Bangkok’, Hollis has a wife and child. Their jobs are different, but even here there are links. Both have jobs that connect them to the outside world in an impersonal way. Arthur works on Wall Street, where ‘he would have worked for nothing’, while Hollis deals in ‘fine books and manuscripts […] After ten years in retail clothing he had found his true life’. In both cases, it is what they have become, and what they have remained, that is crucial to the outcome of the story. In both stories, the men remain true to lives and situations that even the return of their old lovers will not be able to overturn.

The men in both stories have their obsessions and the women play on them. This is especially noticeable in ‘Bangkok’, where the past that Hollis is being reminded of is more than just a perfect love affair between two people. “You remember how you felt about young women at that age.” Carol tells him, and he does. Salter’s description of Hollis is enigmatic: ‘He had a low, persuasive voice. There was confidence in it, perhaps a little too much.’ But Carol gives the reader insight into his motivations and weaknesses, as she reminds him of their past life together and speculates about what he might still like to do:

The men in both stories have their obsessions and the women play on them. This is especially noticeable in ‘Bangkok’, where the past that Hollis is being reminded of is more than just a perfect love affair between two people. “You remember how you felt about young women at that age.” Carol tells him, and he does. Salter’s description of Hollis is enigmatic: ‘He had a low, persuasive voice. There was confidence in it, perhaps a little too much.’ But Carol gives the reader insight into his motivations and weaknesses, as she reminds him of their past life together and speculates about what he might still like to do:

If you were free you’d be able to steam, shower, put on fresh clothes, and, let’s see, not too early to go down to, what, the Odeon and have a drink and see if anyone’s there, any girls.

She also asks: “Do you still like to tie their hands?” If you had just finished reading ‘Palm Court’, you might feel the sudden tightening of a cord; Noreen, the paramour in that story, finds herself ‘lying face down on the bed with her hands tied behind her’. This connection between the two tales is striking, as if the idea has been picked up and re-worked.

In ‘Palm Court’, Arthur’s obsession, if that is the right word, is about preserving his isolation. We are shown his messy work desk and his empty flat. ‘Clarke’s was his real home […] He lived in the bedroom like a salesman.’ Is Salter telling us that really he lives within himself?

The tension between form and content always interests me, and I tend to think that what stories are about is more important, more interesting, than how they go about it. However, in comparing these two stories, which have such similar themes, it is the handling of those themes that attracts my attention.

Both stories are driven by dialogue. In the case of ‘Bangkok’, we have what is virtually a script. In his book On Writing, Stephen King refers to the look of a page of prose fiction telling us something about how it will read. He uses the word ‘fluffy’ to suggest that a page in a story with dialogue should seem light and open, with lots of white space. The word I would use about these pages of Salter’s stories is ‘stringy’, with thin, stretched passages of dialogue down the left hand margin of the page.

“Is that the bedroom?”

“Yes,” he said, but her gaze had drifted from it.

“I just wanted to talk.”

“Sure. About what?” He knew, or was afraid he did.

~ from ‘Palm Court’

“Didn’t you get my message?” She asked.

“Yes.”

“You didn’t call back.”

“No.”

“Weren’t you going to?”

“Of course not,” he said.

~ from ‘Bangkok’

Blocks of longer speech or supporting narrative are sparse, even sparser in ‘Bangkok’, yet both stories end on solid paragraphs of text. The common shape of these draws attention to their common function and their content.

In ‘Palm Court’ it is Arthur who leaves, and a ten-line paragraph closes the story with him walking away, thinking about what has been said. As with most (I’m tempted to say all) good short stories, the image we are left with is ‘the point’, if not the whole enjoyment of the story. Here, that final image is crystallised in the very last word: ‘tears’. In ‘Bangkok’, it is the woman, Carol, who leaves. And as she walks away, Hollis, over three short paragraphs, thinks about what has been said. The story ends with him thinking: ‘It’s not a pretend life.’ We wonder how much he believes that, and how much we do.

In ‘Palm Court’ it is Arthur who leaves, and a ten-line paragraph closes the story with him walking away, thinking about what has been said. As with most (I’m tempted to say all) good short stories, the image we are left with is ‘the point’, if not the whole enjoyment of the story. Here, that final image is crystallised in the very last word: ‘tears’. In ‘Bangkok’, it is the woman, Carol, who leaves. And as she walks away, Hollis, over three short paragraphs, thinks about what has been said. The story ends with him thinking: ‘It’s not a pretend life.’ We wonder how much he believes that, and how much we do.

Perhaps to emphasise both the similarities and differences, the two stories sit back to back in the larger collection. The later story, ‘Bangkok’, is to my mind, the leaner and meaner tale. It is not a mere re-write of the previous story, though. The relationship in it is quite different to that of ‘Palm Court’, which has an innocence and romanticism about it. Arthur’s ‘love’ and life is ‘shallow’, to borrow a word used in the story, but Hollis’s affair with Carol has been a much darker one. In ‘Bangkok’, there is an undercurrent of abuse, and one in which it is hard to apportion innocence or guilt. The mechanics of the stories are far closer than the psychologies that drive them:

“They went together for nearly three years, the best years.”

~ from Palm Court

“You and me.”

“And Molly. As a gift.”

“Well, I don’t know.”

“What does she look like?”

“She’s good-looking, what would you expect?”

“I’ll undress her for you.”

~ from ‘Bangkok’

I’m reminded of Simon and Garfunkel’s song about the many ways ‘to leave your lover’. These two stories could be two of those ways: distinctly similar; distinctly dissimilar.