photo by Jake Bouma

by Morgaine Davidson

Let us begin with a question. When you hear the name of Sherlock Holmes, what precisely springs to mind? Deerstalker hats perhaps. No doubt acres of tweed or hound’s-tooth check jackets. Maybe even comedy magnifying glasses of various shapes and sizes.

It’s ironic that the majority of items, words and phrases associated with the illustrious detective are simply not in the original stories. Yes, even the phrase ‘Elementary, my dear Watson’, which has been hung from every Holmesian flagpole for the past sixty years, isn’t actually the quote it’s been touted as. No, really, it’s not.

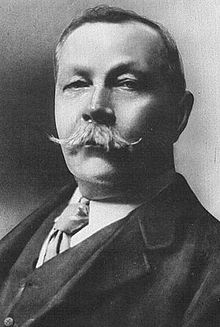

I can say with impunity that nearly all of these hallowed symbols come from the many TV, film, theatre and other graphic reproductions that tend to congregate around the Holmes canon like bobbies round a crime scene. But while these tend to float in and out of fashion, the original stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle seem to cling on to our collective consciousness with a limpet-like tenacity more associated with classic authors such as Wilde, Austen or Dickens.

After all, detective fiction such as this would, under normal circumstances, be pushed kicking and screaming into the dread maw of the beast that is genre fiction, and therefore subjected to derisive and dismissive criticism from literary snobs.

The main reason Doyle’s stories have managed to escape this treatment is down to the uniqueness of the central character. There are plenty of familiar archetypes in detective fiction, usually revolving around cynical mavericks, like Inspector Morse, or bumbling good-natured souls, like Columbo and Miss Marple. But when Sherlock Holmes strode out of 221B Baker Street with his preternatural powers of observation and deduction, he captivated the imaginations of readers almost immediately. As Inspector Jones of Scotland Yard once observed, “he has his own methods, which are a little theoretical and fantastic, but he has the makings of a detective in him”. Little did he know that this eccentric amateur was destined to out-think, out-run, and out-class every police officer on the block.

The main reason Doyle’s stories have managed to escape this treatment is down to the uniqueness of the central character. There are plenty of familiar archetypes in detective fiction, usually revolving around cynical mavericks, like Inspector Morse, or bumbling good-natured souls, like Columbo and Miss Marple. But when Sherlock Holmes strode out of 221B Baker Street with his preternatural powers of observation and deduction, he captivated the imaginations of readers almost immediately. As Inspector Jones of Scotland Yard once observed, “he has his own methods, which are a little theoretical and fantastic, but he has the makings of a detective in him”. Little did he know that this eccentric amateur was destined to out-think, out-run, and out-class every police officer on the block.

It’s easy to see why the public fell for Doyle’s creation. The individual plots are many and varied, ranging from larger issues like murder, blackmail and jewel theft, to smaller and positively insignificant everyday incidents.

Despite the variety of cases, though, the narrative structure of the majority of these short stories is reassuringly formulaic. Holmes and Watson are usually enjoying some friendly banter in 221B, when – “quick man! I hear a hansom drawing up outside! And here, Watson, unless I am very much mistaken, is our client now upon the stair. Come in!”

Enter the client: usually in an absolute fug of confusion or fear, who Holmes will generally comfort and insult in equal measure. It’s left to the reassuring Watson to convince the prospective client that this madman in the mouse-coloured dressing gown is their best option.

Once the baffled client is gently prodded out the door, one of two things could happen. Holmes may immediately spring to life in a fit of nervous energy, bounding around like a mad march hare in various unsavoury disguises, picking up tantalising clues and making obscure connections. Alternatively, he might lounge around, brow furrowed and eyes gazing into infinity, smoking his pipe and letting that extraordinary brain sift through the data provided… before he then leaps into action like a mad march hare.

The rest of the story will be a positive palaver of baffling circumstances, mysterious suspects, strange allies and comic interludes from bumbling police officials, topped off with much brandishing of revolvers. If this seems fairly ordinary for a detective story, just remember that Sherlock Holmes was one of the first literary detectives in the world. These stories are the bedrock of crime fiction, and the form from which all others have grown.

Eccentric, cerebral, philosophical and positively heartless, Holmes is hardly conventional hero material. He is a fascinating study, yet one often wonders if he is quite completely human. There is something otherworldly and aloof about this man who seems to know everything at a glance. But, if one probes deeper beneath the surface, it becomes clear that Holmes is possessed of a great heart as well as a great brain.

In a personal favourite story of mine, ‘The Adventure of the Three Garridebs’, there is a glorious moment when Holmes, glowering with eyes of flint at a captured villain, snarls with uncharacteristic vehemence, “…if you had killed Watson, you would not have got out of this room alive”. Poor Watson, who is lying dazed on the floor after being shot in the leg, is astonished:

It was worth a wound – it was worth many wounds – to know the depth of loyalty and love which lay behind that cold mask. The clear, hard eyes were dimmed for a moment, and the firm lips were shaking.

This is a touching revelation from Doyle that reveals something rather special. The true soul of the Sherlock Holmes stories is not the time spent gallivanting around fighting organised crime and dastardly Empire-threatening plots. Rather, it lies with the little  things. Those small, personal moments of revelation when Doyle brings out the subtle side of his detective, showing a gentle courtesy and fierce loyalty, which is positively enthralling to read. It proves that he is indeed human and it makes his misanthropic side easier to accept.

things. Those small, personal moments of revelation when Doyle brings out the subtle side of his detective, showing a gentle courtesy and fierce loyalty, which is positively enthralling to read. It proves that he is indeed human and it makes his misanthropic side easier to accept.

However, despite the unbridled popularity of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle grew tired of his creation. He wanted to devote more time to the historical novels that were his true passion. So he threw his detective off the edge of a waterfall.

It was a shame, then, that his actions didn’t sit well with the public, for he was forced to bring good old Sherlock back from the dead for ‘The Adventure of the Empty House’. There was no going back after that and the canon of Sherlock Holmes stories continued to grow and grow. Their popularity was not just confined to England either; people all over the world were falling in love with the mighty duo. Doyle often received fan mail addressed to Holmes and Watson, and he occasionally had to fend off excitable Americans determined to meet and shake the hand of Mr. Holmes himself.

I doubt there are many people to whom the name Sherlock Holmes is unfamiliar, and part of this must be due to the numerous adaptations of the stories that have cropped up over the years. There have been stage productions, television series, films, fan-fiction and graphic novels all centering on the great detective. Not that there’s anything wrong with this. Quite the opposite. It’s wonderful that a love of Sherlock Holmes still persists within our modern culture. But, dear reader, if you truly wish to understand why these tales have inspired generation after generation of Sherlockians, you must, ultimately, return to the source. There is nothing quite like those original short stories, and there never will be. Holmes was, and always shall be, the greatest detective who never lived.