(‘Early morning at canal in Venice’ © Tommie Hansen, 2015)

SERIOUSLY, DON’T LOOK NOW

by BRENDAN O’DEA

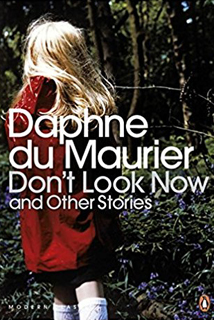

Nicholas Roeg’s 1973 screen adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s short story ‘Don’t Look Now’ is visually stunning, haunting and thought-provoking. Many people find the film disturbing. I was unable to persuade any friend to accompany me to view it at a local cinema, some years ago. Yet, for some strange reason, I have always been fascinated by the film, finding it intense, beautiful and cryptic. The original story can be found in the du Maurier anthology entitled Don’t Look Now and Other Stories, published in 1971.

‘Don’t Look Now’ shows how short stories can provide superb material for feature-length films. They offer a ‘bare bones’ framework on which the flesh of the film can be hung without compromising the integrity of the original. They act as a kernel for the film, around which a talented director can create a dramatic visual body. And, Roeg, with typical flair, conjures up a sumptuous kaleidoscope-like experience.

Du Maurier’s story and its screen counterpart differ significantly. Du Maurier crafts her dialogue whereas Roeg masters the visual. In the story, John and Laura’s daughter dies from meningitis. In the film, she drowns, allowing Roeg to mirror events in Venice that centre on water, dampness and decay. Du Maurier shows the couple holidaying in Venice. Roeg has John conserving sacred art in magnificent Venetian churches; he is shown re-assembling intricate mosaics while trying to make sense of the turmoil surrounding him. Du Maurier’s brief reference to the couple’s intimacy transforms into a love-making extravaganza on screen.

Roeg uses artistic licence to enhance the visual side of the tale, but his flamboyant film is reliant on du Maurier’s original for its substance. The film is like a mosaic that has been carefully assembled to allow the viewer to see the full picture. Du Maurier’s story unfolds in a more clear-cut fashion. With its heavy emphasis on dialogue, girded by psychological tension, it offers a strong foundation for adaptation to screenplay.

Du Maurier portrays John and Laura on holiday in Venice and grieving for their recently-deceased child, Christine. The story is narrated from a third-person limited viewpoint focused on John, so our understanding is restricted by his perception of events. This leaves us partially blind to impending danger. In the latter half of the account, when English tourists try to engage John on the subject of a recent local murder, he is ignorant of the fact. We, the readers, are also unaware of this horror, even though:

Du Maurier portrays John and Laura on holiday in Venice and grieving for their recently-deceased child, Christine. The story is narrated from a third-person limited viewpoint focused on John, so our understanding is restricted by his perception of events. This leaves us partially blind to impending danger. In the latter half of the account, when English tourists try to engage John on the subject of a recent local murder, he is ignorant of the fact. We, the readers, are also unaware of this horror, even though:

Venice has talked about nothing else. It’s been in all the papers, on the radio, and even in the English papers. A grizzly business.

This darkens an already gloomy atmosphere and alerts us to John’s vulnerability in his strange surroundings.

We imagine John to be more logical and ‘in control’ than Laura. However, his strength falters as he fails to bend to events that are beyond his control. Problems begin when they encounter elderly Scottish twin sisters in a restaurant, one of whom is blind and clairvoyant and claims to be able to see Christine. Laura is immediately bewitched and John finds this unsettling:

The desperate urgency in her voice made his heart sicken. He had to play along with her, soothe, do anything to bring back some sense of calm.

At the cathedral they view mosaics. Laura is particularly moved by one of the Virgin and Child. John spys the twins again and is overcome with a sense of foreboding. Back at their hotel, they make love for the first time in weeks, lulling John into a false sense of security. Afterwards, exploring dark streets, they hear a horrible cry, which sounds like someone being strangled. John sees a young girl in a pixie-hood jumping between boats on the canal. He watches for several minutes, captivated, concerned for her safety. Has grief made him more attuned to people’s vulnerability?

They bump into the twins again and Laura informs John that the blind sister warned that they were in danger if they remained in Venice, and suggested that John was psychic but didn’t know it. John is furious.

Du Maurier, like many writers of her generation, was beguiled by ‘vanishing’ Venice, and on the way back to the hotel, John ponders how the city is decaying and sinking. He seems to be drowning in his emotions and we sense a gulf developing in the couple’s relationship:

Their heels made a ringing sound on the pavement and the rain splashed from the gutterings above. A fine end to an evening that had started with brave hope, with innocence.

John and Laura receive a telegram from their son’s school notifying them that he is ill. Laura leaves almost immediately for England. Later, John checks out of the hotel and catches a ferry from San Marco. Perhaps sensing all is not well, he wonders if they will ever return to the city, the scene of their honeymoon.

Suddenly, he becomes convinced he sees a distressed-looking Laura, with the twins, on a tourist ferry returning to Venice. He grasps for a rational explanation; maybe a cancelled flight? He returns to the hotel but Laura never shows. John, thinking rigidly, refuses to consider he may be mistaken, leading us, also, to believe Laura is still in Venice.

John reports the matter to the police, expressing concern over the twin’s intentions, only to receive a baffling phone call from Laura, in England, reassuring him that all is well. His predicament has turned surreal. He starts drinking, clouding his judgement, and sneaks out to dinner before explaining his mistake to anyone. We wince at his unwise evasiveness.

When John hears that the twins are at the police station, he goes there to explain. He finds them distressed and confused, apologises and accompanies them back to their lodgings. They inform John that what he saw on the ferry was a vision of the future and that he had been confused by his ‘second-sight’. The blind twin goes into a disturbing trance, frothing at the mouth and collapsing. They help her inside and John departs. We intuit danger and our concern for him intensifies.

Before long, John is lost in the half-familiar streets. He glimpses the same hooded girl being pursued by a shadowy man. John realises he is near where they previously heard the dreadful cry and remembers the recent murders. He is concerned and eventually finds the child huddled and sobbing in a derelict building. He approaches reassuringly. She turns, her hood falling to the floor. John faces a grotesque-looking adult female dwarf who slashes his throat with a knife. He sees Laura and the sisters on the boat again, this time recognising the future, when they will attend his funeral. The reader leaves John as he lies dying. The coup-de-grace has been delivered and all hopes of normalcy shattered.

‘Don’t Look Now’, with its well-crafted plot, is a fine example of short fiction at its best, but it is difficult to separate the story from its screen adaptation — the latter often overshadows the former in terms of impact. Roeg’s extravagant film may have brought the story fame, or notoriety, but reading Du Maurier’s work gives us an insight into a keen, creative and sensitive literary mind. Her words conjure up scintillating scenes no less evocative than the story’s cinematic counterpart. Even those of us who have never visited Venice may be familiar with it through paintings, cinema and literature. Du Maurier writes of its magnificence, with ‘so many impressions to seize and hold, familiar loved facades, balconies, windows, water lapping cellar steps of decaying palaces’, transporting us into the heart of the action as eager witnesses.

‘Don’t Look Now’, with its well-crafted plot, is a fine example of short fiction at its best, but it is difficult to separate the story from its screen adaptation — the latter often overshadows the former in terms of impact. Roeg’s extravagant film may have brought the story fame, or notoriety, but reading Du Maurier’s work gives us an insight into a keen, creative and sensitive literary mind. Her words conjure up scintillating scenes no less evocative than the story’s cinematic counterpart. Even those of us who have never visited Venice may be familiar with it through paintings, cinema and literature. Du Maurier writes of its magnificence, with ‘so many impressions to seize and hold, familiar loved facades, balconies, windows, water lapping cellar steps of decaying palaces’, transporting us into the heart of the action as eager witnesses.

We empathise with John and are concerned for him as he falls victim to his own failings, events beyond his control, and the beautiful and mysterious, but decaying and sinking, city. We can relate to his very human reactions when faced with grief, intrusive strangers, a strained relationship, a foreign language and his newly discovered clairvoyance. We sense his helplessness when confronted with the sinister sisters twice in a day:

He felt himself held, unable to move, and an impending sense of doom, of tragedy, came upon him. His whole being sagged, as it were, in apathy, and he thought, ‘This is the end, there is no escape, no future.’

It is appropriate that we empathise with John, because we, too, are confused by events as they unfold in the narrative and, like John, fail to grasp their significance.

Du Maurier builds up tension expertly. John and Laura, as a couple, come across as mundane. The only element of drama is Venice itself, and, perhaps, the couple’s grief, which creaks like a straining floodgate in the background. What, at first, appears a leisurely, even meandering, tale leads us blindly and unwittingly towards a crescendo of horror. The ensuing action throws John, and the reader, into confusion. The denouement is delivered with panache, and is so devastating that it looks inevitable, almost predestined, permitting everything which preceded it to fall neatly into place. As the spine-chilling story closes, we see what we failed to see before and, maybe, we begin to regret having dared to look in the first place.

And he saw the vaporetto with Laura and the two sisters steaming down the Grand Canal, not today, not tomorrow, but the day after that, and he knew why they were together and for what purpose they had come. The creature was gibbering in its corner. The hammering and the voices and the barking dog grew fainter, and, ‘Oh God,’ he thought, ‘what a bloody silly way to die…..’

~

Brendan Joseph O’Dea lives and works in Leicestershire. He is passionate about history, religion, spirituality and literature. He writes fiction and non-fiction in his spare time, an activity he finds very therapeutic. He especially values the short story as a creative medium. He enjoys reading Gothic fiction, crime fiction and biographies.