photo by Mikhail Noel

by Karen Whiteson

In a radio interview in 1947, Elizabeth Bowen was asked to discuss the book which had most influenced her early years; she chose H. Rider Haggard’s She. Bowen first read this Edwardian Gothic novel at the age of twelve, when she had ‘exhausted the myths of childhood…when I was finding the world too small…having developed a sort of grudge against actuality.’ For Bowen, the experience of reading this book was ‘the first totally violent impact I ever received from print. After She, print was to fill me with apprehension. I was prepared to handle any book like a bomb.’

This revelation of the power of the printed word went beyond passive escapism and showed the means by which the world could be re-enchanted over and over again. It revealed to Bowen her own desire to write.

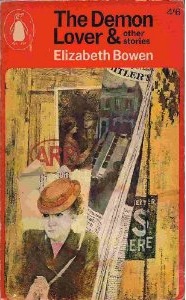

Bowen’s short story ‘Mysterious Kôr’, from her collection The Demon Lover, was written and set during the London blitz. This twelve page story gives a potent evocation of wartime’s impact on the unconscious life of the city. It begins:

Full moonlight drenched the city and searched it; there was not a niche left to stand in. The effect was remorseless. London looked like the moon’s capital – shallow, cratered, extinct.

Saturated by the moon’s totalising light, the city becomes a means of transmitting currents of energy, images and sensations, hence the cinematic, heightened quality of the writing.

As the Germans will no longer come in the light of the full moon, the moon itself acts as an eerie surrogate for the absent invaders; rendering the black-out futile. The conflation of moonlight with an annihilating force is underlined by the description of the crowd:

…a trickle of people came out of the Underground, around the anti-panic brick wall. These all disappeared quickly…as though dissolved in the street by some white acid.

Pepita is one to emerge into the street, along with Arthur, her squeeze, and she names this scene ‘Mysterious Kôr’. The phrase comes from a poem that is recited in fragments throughout the story. It was written by Andrew Lang in response to Rider Haggard’s novel She. Pepita tells Arthur that it was conceived:

“…when they thought they had got everything taped, because the whole world had been explored, even the middle of Africa…The world is disenchanted, it goes on. That was what set me off hating civilisation.”

In She, Kôr is the lost dominion of the eponymous queen, also known as Ayesha. Having bathed in the fires of everlasting life, Ayesha now awaits the reincarnation of her lost lover and the full restoration of her powers. In ‘Mysterious Kôr’, Pepita’s take on the poem provides a sensuous response from Bowen: “What it tries to say doesn’t matter: I see what it makes me see.”

In She, Kôr is the lost dominion of the eponymous queen, also known as Ayesha. Having bathed in the fires of everlasting life, Ayesha now awaits the reincarnation of her lost lover and the full restoration of her powers. In ‘Mysterious Kôr’, Pepita’s take on the poem provides a sensuous response from Bowen: “What it tries to say doesn’t matter: I see what it makes me see.”

Her reading of Haggard’s novel as a child in Ireland also influenced the way Bowen was to perceive the London she had not yet seen; Holly, the narrator in She, draws numerous analogies between the two cities. Thus, Bowen was predisposed to see London as ‘Kôr with the roofs still on’.

In ‘Mysterious Kôr’, the moonlight reveals London as a palimpsest for another realm. When Callie, Pepita’s flat-mate, parts the curtains to let the moonlight ‘march’ into the ‘flatlet’, which has been converted from a Victorian drawing room, it x-rays through the veil separating one era from another:

…out stood the curves and garlands of the great white marble Victorian mantelpiece of that lost drawing room; out stood, in the photographs turned her way, the thoughts with which her parents had faced the camera, and the humble puzzlement of her two dogs at home.

Callie is awaiting the return of the stop-outs and, having opened the curtains, she drinks in the moon’s ‘white explanation’ which, to her mind, ‘exonerates’ the lovers’ late return. She goes to her bed which, in order to accommodate Arthur, she is to share with Pepita:

Callie lay down again. Her half of the bed was in shadow, but she allowed one hand to lie, blanched, in what would be Pepita’s place. She lay and looked at her hand until it was no longer her own.

When Arthur and Pepita finally arrive, she introduces herself to Arthur with an awkwardly polite handshake. ‘She rather beheld than felt his red-brown grip on what still seemed her glove of moonlight.’ This recurring image of the disembodied hand culminates in a final gesture of unconscious violence, when, later, the sleeping Pepita slaps Callie in the face.

If this scene gives the flickering impression of a black-and-white movie then it is because the moving image without a body is a definition of cinema. The presence stands for absence, as the glove stands for the hand, as the moonlight substitutes for the Luftwaffe (aerial warfare) – it is inherently cinematic. As Gilles Deleuze says, in his wondrous Cinema 2: The Time Image, cinema ‘contradicts all natural perception. What it produces in this way is the genesis of an unknown body’.

Here, the camera-eye of the moonlight casts its film of hallucination wherever it falls: dissolving the crowds in white acid, sculpting a hand into a glove of light. Whether its effect is corrosive or enchanting seems secondary to its phantasmic force.

This force is evident in Callie’s vigil at the window: ‘Below the moon, the houses opposite her window blazed back in transparent shadow; and something – was it a coin or ring? – glittered halfway across the chalk-white street.’ Much later, after the lovers have returned, after Callie has been woken by Arthur stumbling about in the dark, she opens a window and finds the moonlight has receded, and that ‘whatever had glittered there, coin or ring, was now gone’. This object serves as an indication of the moon’s power in its presence and disappearance.

This force is evident in Callie’s vigil at the window: ‘Below the moon, the houses opposite her window blazed back in transparent shadow; and something – was it a coin or ring? – glittered halfway across the chalk-white street.’ Much later, after the lovers have returned, after Callie has been woken by Arthur stumbling about in the dark, she opens a window and finds the moonlight has receded, and that ‘whatever had glittered there, coin or ring, was now gone’. This object serves as an indication of the moon’s power in its presence and disappearance.

Kôr’s initial appearance – heralded by Arthur’s bemused observation, “you mean we’re there now, that here’s there, that now’s then” – was just as sudden as its subsequent disappearance. The abruptness of Kôr’s epiphanies are similar to the behaviour of desire that arrives like a bolt out of the blue. Arthur realises he ‘had not seen Pepita coming; their love had been a collision in the dark’. Both death and desire arrive from offscreen.

In her novel The Heat of the Day, also set in wartime, Bowen described ‘the thinning of the membrane between this and that’ – allowing for fleeting incidents of intense, almost telepathic communication between her characters. She went on to explain, ‘the hallucinations are an unconscious, instinctive, saving resort on the part of the characters’.

‘Mysterious Kôr’ encapsulates this concept of hallucination as collective experience. Towards the end of the story, Arthur recounts to Callie an earlier exchange with Pepita about Kôr:

“So we began to play, we were off in Kôr.”

“Core of what?”

“Mysterious Kôr – ghost city.”

“Where?”

“You may ask. But I could have sworn she saw it, too. A game’s a game, but what’s a hallucination? You begin by laughing, then it gets in you and you can’t laugh it off…”

The moment Arthur and Pepita begin to play is after they emerge from the Underground, when something makes them turn round to face the way they came:

His look up at the height of a building made his head drop back, and she saw his eyeballs glitter. She slid her hand from his sleeve, stepped to the edge of the pavement and said: “Mysterious Kôr”.

Here, Pepita’s invocation of Kôr is triggered by seeing the glitter in Arthur’s gaze as he eyeballs the moon, which she sees, as it were, through his eyes. Lunar light being itself reflected, Pepita reflects it back. “Kôr is not really anywhere,” Arthur remarks. Rather it is precisely in the spaces ‘between this and that’.

The story ends on a note of radical ambiguity. After slapping Callie in the face Pepita:

…lay still, as she had lain, in an avid dream, of which Arthur had been the source, of which Arthur was not the end. With him she looked this way and that, down into the wide, void, pure streets, between statues, pillars and shadows, through archways and colonnades. With him she went up the stairs down which nothing but moon came; with him…[she] mounted the extreme tower. He was the password but not the answer: it was to Kôr’s finality that she turned.

Here, the sense of marvel passes from the object-of-desire to the act of looking. The gaze endlessly drinks in the gaze. Yet, at the same time as conjuring this spacious vision, the dream’s mise-en-scène recalls the deathly neo-classical vistas of the Nazi aesthetic, and the invention of ‘ruin value’. This concept, invented by Hitler’s Minister of Armaments, Albert Speer, ruled that, in order to bear eternal witness to the grandeur of the Third Reich, buildings should be constructed in such a way so as to leave behind impressive ruins. Near the start of ‘Mysterious Kôr’, Pepita says that Kôr has no history and that its timelessness renders the place indestructible: “There’s not a crack in it anywhere for a weed to grow in; the corners of the stones and the monuments might have been cut yesterday.” The architecture of Kôr delivers ‘ruin value’ par excellence.

In She, the city of Kôr faces backwards, towards the End of Empire. In Pepita’s vision, Kôr is both the ‘pure locus of the possible’ and the fantasy of its annihilation. “The war shows we’ve by no means come to an end” – she declares – “If you can blow whole places out of the world, you can blow whole places into it.”

Each time I re-read it, this tiny masterpiece, written in the eye of the storm, preserves its darkly glittering riddle.

Thanks so much for posting my article on Scoop it…must check it out for myself (and for my CW students, also)