('Sony DSC' © Fern092, 2013)

*

SEARCHING FOR BORGES IN THE LIBRARY OF BABEL

by AIMEE McCAGUE

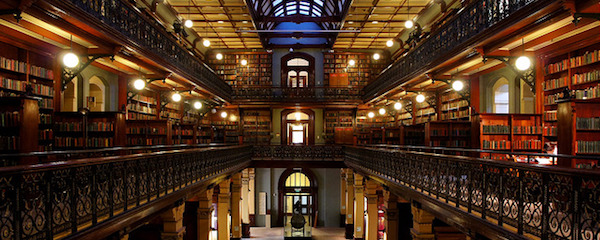

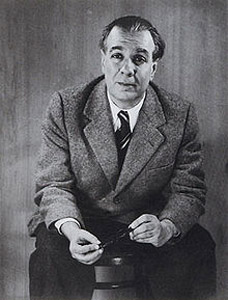

It can be easy to think of a writer’s work in terms of the writer’s life. One is often reminded of Hemingway’s difficult personality and misogynistic tendencies when reading one of his short stories, and it is almost a given that, when considering the poems of Sylvia Plath, the conversation turns to her depression and tragic suicide. Similarly, when discussing the works of the great Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges, the word ‘recluse’ gets thrown around. While this is a commonly held opinion, I prefer to think of Borges in terms of my favourite of his short stories: ‘The Library of Babel’.

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with vast air shafts between, surrounded by very low railings.

Borges’ story tells of an infinite library, in which every book imaginable is stored. The library consists of an infinite number of connected hexagons with a precise number of shelves, each containing a precise number of books. The library holds every book that has ever been written or might ever be written, as well as every single variation possible – such as a single comma or letter out of place. Added to this is the concept of the Book-Man and the ‘catalog of catalogs’, a perfect index that lists every single book in the library:

Borges’ story tells of an infinite library, in which every book imaginable is stored. The library consists of an infinite number of connected hexagons with a precise number of shelves, each containing a precise number of books. The library holds every book that has ever been written or might ever be written, as well as every single variation possible – such as a single comma or letter out of place. Added to this is the concept of the Book-Man and the ‘catalog of catalogs’, a perfect index that lists every single book in the library:

On some shelf in some hexagon it is argued, there must exist a book that is the cipher and perfect compendium of all other books, and some librarian must have examined that book; this librarian is analogous to a god.

What is wonderful about Borges’ prose is that even with such technical language – including various measurements and numeric details – he stills manages to create a fantastical world that tells the reader so much about the human condition, despite the lack of a distinct protagonist. What this story explores, in relation to the human condition, is the need for a higher power, or a God. Just as human beings have followed religion for thousands of years, the inhabitants of the library have a god-like figure in the form of the Book-Man. Similarly, the quest for the so-called ‘catalog of catalogs’ is akin to a quest for knowledge, and the power that comes from possessing this knowledge.

The best example of this concept comes when the inhabitants of the library look for their ‘Vindications’ – books that supposedly tell the entire history of a person, and therefore how they will die. This search culminates in acts of violence. The narrator states:

These pilgrims disputed in the narrow corridors, proferred dark curses, strangled each other on the divine stairways, flung the deceptive books into the air shafts, met their death cast down in a similar fashion by the inhabitants of remote regions.

Here, Borges shows the reader how human beings will always search for meaning in their lives. Even with all the possible knowledge in the universe at their fingertips, these people still want to know more. For me, this links back to the idea of confusing an author with their work: while it isn’t always the case, the author’s presence can generally be felt in a story and you can be left wondering how and why the story materialised.

Herein lies the whole problem with close reading. Instead of just enjoying a literary work on its own merits, students of creative writing are often encouraged to analyse every little detail, searching for meaning in a text. This extends to receiving an author’s biography before even learning about the work. Life details may be superfluous to the story, but nonetheless, they can cloud a reader’s judgment. Borges was known to be an avid book reader, famously stating: ‘I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.’ I knew of this facet of his personality, and so on my first reading of ‘The Library of Babel’ my initial thought was: Wow, this is Borges’ ultimate fantasy, isn’t it? Of course, sometimes it may be of note to know at what stage in a writer’s career a certain story was written, or if a story was triggered by an important event in the author’s life. But to say the library of his story is simply Borges’ picture of Heaven would deny any meaning he tried to inject.

Herein lies the whole problem with close reading. Instead of just enjoying a literary work on its own merits, students of creative writing are often encouraged to analyse every little detail, searching for meaning in a text. This extends to receiving an author’s biography before even learning about the work. Life details may be superfluous to the story, but nonetheless, they can cloud a reader’s judgment. Borges was known to be an avid book reader, famously stating: ‘I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.’ I knew of this facet of his personality, and so on my first reading of ‘The Library of Babel’ my initial thought was: Wow, this is Borges’ ultimate fantasy, isn’t it? Of course, sometimes it may be of note to know at what stage in a writer’s career a certain story was written, or if a story was triggered by an important event in the author’s life. But to say the library of his story is simply Borges’ picture of Heaven would deny any meaning he tried to inject.

Ultimately, however, we are left like the inhabitants of the library – searching for something we may never find. Because no matter how much we may try to know about the author’s life, the author is the library itself: infinite and complex. As Borges himself said, in an interview with El País in 1981: ‘I am not sure that I exist, actually. I am all the writers that I have read, all the people that I have met, all the women that I have loved; all the cities I have visited.’

For me, many words other than ‘recluse’ spring to mind when talking about Borges: literary genius, master linguist, lover of books. And he may have been all of these things but that does not matter. What matters is what he chose to put on the page.

~

Aimee McCague is a writer from Monaghan, Ireland. She is currently studying the Creative Writing MA in Royal Holloway, University of London, having recently graduated from National University of Ireland, Galway with joint honours in English and Spanish. Aimee has had short stories published in NUIG’s Ropes publication, as well as having a story shortlisted for the James Plunkett Short Story Award. She is currently situated in Dublin and is working on her debut novel.

Aimee McCague is a writer from Monaghan, Ireland. She is currently studying the Creative Writing MA in Royal Holloway, University of London, having recently graduated from National University of Ireland, Galway with joint honours in English and Spanish. Aimee has had short stories published in NUIG’s Ropes publication, as well as having a story shortlisted for the James Plunkett Short Story Award. She is currently situated in Dublin and is working on her debut novel.