photo by Kevin Tuck

Shortlisted in the 2012 THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition

by Eamonn Griffin

From the publication of his first novel, The Restraint of Beasts, in 1998, Magnus Mills has developed something of a reputation for quietly menacing studies of very English forms of male ritual, working habits, and developing senses of unease and absurdity. Sometimes these occur in everyday settings: Restraint concerns three men cooped up in a caravan who are working on a fencing project; 1999’s All Quiet on the Orient Express is about a Lake District holiday for one man which develops into an inescapable set of obligations. Sometimes the settings are more intangible, if not wholly fantastical: Mills’ most recent novel, 2011’s A Cruel Bird Came to the Nest and Looked In observes an isolated principality which unravels as a railway is being built from a neighbouring state towards it. 2003’s The Scheme for Full Employment is perhaps the most cohesive in terms of distilling the various strands of Mills’ fascinations – depicting an alternative England where the whole economy is dependent not only on the driving of vans full of parts from warehouse to other, but not questioning what the parts are for.

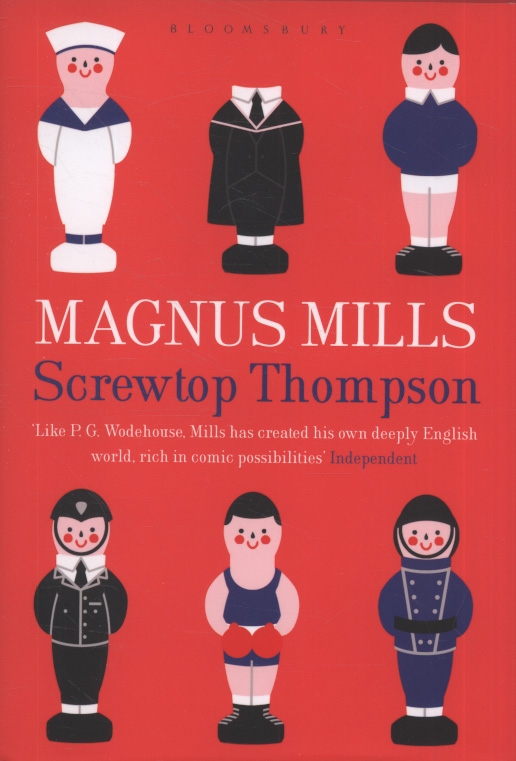

Though the bulk of Mills’ output has been in novel format, he’s produced some short fiction. Screwtop Thompson, published in 2010, is a compilation of two earlier small press collections of stories, Once in a Blue Moon and Only When the Sun Shines Brightly with three additional new tales. Each of the eleven pieces collected in Screwtop Thompson fits in with the wider themes apparent in Mills’ work. This recommendation focuses on just two of the stories as emblematic of his writing: ‘Hark the Herald’ and ‘Vacant Possession’.

Though the bulk of Mills’ output has been in novel format, he’s produced some short fiction. Screwtop Thompson, published in 2010, is a compilation of two earlier small press collections of stories, Once in a Blue Moon and Only When the Sun Shines Brightly with three additional new tales. Each of the eleven pieces collected in Screwtop Thompson fits in with the wider themes apparent in Mills’ work. This recommendation focuses on just two of the stories as emblematic of his writing: ‘Hark the Herald’ and ‘Vacant Possession’.

First, the similarities between the stories, and indeed, through the rest of the pieces in Screwtop Thompson, are striking and indicative of a communicated sense of both purpose and control. Both ‘Hark the Herald’ and ‘Vacant Possession’ are narrated in the first person by a vaguely anonymous male, a trait shared by each of the eleven pieces collected here – and which further echoes across Mills’ novels. The two stories each have two speaking characters. They are focused in time, the stories each taking place over two separate days, and space, having their action restricted to a single primary location (a bed-and-breakfast in ‘Hark’, a run-down country house in ‘Possession’). We learn little about the protagonist (the narrators of both ‘Possession’ and ‘Hark’ are given neither physical description or name), or the secondary character in either story; Mills evidences huge control over his material, offering spaces for the reader to fill with themselves.

Formal similarities extend further when issues concerning the stories’ themes are explored. There’s a shared mood, an unspoken menace, in the two pieces. This begins with the physical locations – have you ever stayed in slightly out-of-the-ordinary accommodation, where you can’t quite put your finger on what’s unsettling you? Ever been in a house with a disquieting atmosphere that you try to, but can’t quite, shake from your mind? The stories then extend to low-key but accumulating episodes – a noisy overheard party then a missed breakfast in ‘Hark’, a disturbed nap and a squeaky floorboard, which serve to develop feelings of unease, in ‘Possession’:

For some reason I’d begun to feel rather unwelcome on that landing, as though anything I did would be regarded as interfering.

These are counterpointed by the ordinariness of the surroundings. Mills’ fictive worlds are provincial, mundane, even drab – to some extent this is achieved through the ordinariness of the narrators themselves, individuals who posit themselves as normal but have unresolved questions surrounding them. Why is the protagonist of ‘Hark’ staying alone in a bed-and-breakfast over the Christmas holiday, for example? Why are the two workers at the centre of ‘Possession’ similarly staying away from their own homes in the empty and odd country house, but also making the job last longer than it might otherwise?

In terms of basic structure, in protagonist and in voice, then, there are many observable similarities across much of Mills’ work. These similarities deepen when we turn to the question of theme. What are these stories about? At the surface level of story action, one recurring theme is that of reader involvement. We don’t find out what’s behind the protagonist at the end of ‘Possession’. We get no confirmation of what’s happening in the bed and breakfast in ‘Hark’. Is the hotelier playing some kind of trick on his visitor? Do the other guests exist?

In terms of basic structure, in protagonist and in voice, then, there are many observable similarities across much of Mills’ work. These similarities deepen when we turn to the question of theme. What are these stories about? At the surface level of story action, one recurring theme is that of reader involvement. We don’t find out what’s behind the protagonist at the end of ‘Possession’. We get no confirmation of what’s happening in the bed and breakfast in ‘Hark’. Is the hotelier playing some kind of trick on his visitor? Do the other guests exist?

What we are left with, though, is the effect that these events have had on the person relating the story back to us. Mills doesn’t deal with men who are confident or comfortable in expressing themselves openly; when they do, they are hesitant, apologetic – as in ‘Hark’, for example:

“It’s a shame you had to miss the full breakfast, but of course you will be entitled to a packed lunch.”

“When?”

“When you go out.”

“Oh…er, OK, thanks.”

“You will be going out, won’t you, sir?”

“Well I hadn’t definitely decided, but, yes, I expect I most definitely will.”

This reluctance extends outside of the story-space; in narrating in first-person, the protagonist is reluctant in explaining himself and what’s actually happened in the tale he’s relating to us. The reader is then left with questions, not just of story event, but of a set of consequences. What’s happened? How does the protagonist feel now? What are they trying to communicate? Given the information that they’ve related, and in particular its lack, how do we feel about the absence or omission of detail? The reader is being involved, being drawn into the making of meaning by finding themselves in one of two positions – as either the “I” of the story, or as an investigator after the event, trying to piece together what might have happened. The former is perhaps the more persuasive approach; what are we scared of? What upsets us? Would we have acted any differently when put in the same situations as the men in the centre of the action?

Mills’ stories, by refusing to be definitive, by not allowing the perhaps more straightforward pleasure of a resolution, not only engage us by involvement in puzzling out what might be going on, but they mutate. The story changes with each reading, as we change, and as our attitudes to the story and the contexts of its reading change.

Mills prefers the low-key, the straightforward as a means of communication, even if (perhaps especially when) the extra-ordinary is being intimated. His narrators tend to the blank, are shy, non-confrontational. They express themselves in simple terms. Their pleasures are likewise simple ones, and their lives are punctuated, even structured, by ordinary things.

Mealtimes and breaks from work are a recurring feature – breakfasts, sandwiches, cups of tea. Organised meals (the missed cooked breakfast, apparent confusion over evening dining arrangements, a packed lunch) organise the narrative of ‘Hark’. Elsewhere, kettles are boiled and rests from manual or low-paid labour sought. Tea-drinking permeates ‘Possession’, and its story of two men engaged on a job of installing a cattle-grid, not just in terms of giving the workers excuses to pause and chat or reflect, but in terms of mapping time and of using a mundane act (the making of tea) to induce unease. Trips to the kettle become threatening in themselves; the time it takes a brew to cool and the drinking or not drinking of cooled tea gains significance.

I heard water surging through the pipes as he [Noz] filled the kettle and rinsed out the mugs. A few seconds passed. The water stopped running and the whistling ceased. Noz had fallen silent as he waited for the kettle to boil, apparently quite content to be all alone at the bottom of the stairs.

These are ordinary, perhaps unexceptional lives, articulated through quotidian pleasures, into which a period of oddity has intruded; an oddness which has had a long-lasting effect, because otherwise these normally-reticent people would not be telling their stories to us.

These are ordinary, perhaps unexceptional lives, articulated through quotidian pleasures, into which a period of oddity has intruded; an oddness which has had a long-lasting effect, because otherwise these normally-reticent people would not be telling their stories to us.

These aspects redouble in effect. Ordinariness, plain language, absence of crude drama, lack of assertiveness in the narrators, an unwillingness to quite pin down what’s going on. We’re drawn as readers into a zone which is both comic and threatening. Comic in the sense of the comedy of awkwardness, of lack of social finesse, of avoidance of the issue; a comedy of recognition and of acknowledgement that where, if the same were to happen to you, it would be disquieting, but when others are involved, then there’s some humour in their situation.

They are threatening not just in the English bleakness of the characters’ situations, but in the unspoken circumstances behind their being involved in the narrative in the first place, in the absence of definitive antagonists, in the sense that, in telling their stories to us, these effects are being communicated and thus spread rather than dealt with and closed off. At the end of ‘Hark’, for example, the narrator is left awake and restless, not because of a noisy festive gathering downstairs or in another room, but because of its absence:

I sat on the bed and listened. At any moment I hoped to hear the sound of merrymakers returning, followed soon afterwards by glasses tinkling and joyous voices calling me down to be with them.

Yet all I heard was the sea as it broke against the shore.

He doesn’t know by now if there are even any other guests there, as he hasn’t seen them himself; not hearing a party he’s not quite been invited to leaves him, and now us, in doubt as to what’s going on.

The ending of ‘Possession’ is perhaps even eerier. The narrator’s colleague, Noz, has gone to make tea in the weird little kitchen at the bottom of the stairs, but all has gone quiet. Too quiet?

And as I sat in that room, watching the door and listening, it never occurred to me to look over my shoulder.

Now that’s how you end a story.

Magnus Mills’ work – exemplified here by two short stories, and throughout the whole of Screwtop Thompson, and on into his work in novel format too – is characterised by its constraints: Englishness, routine, lack of information, anonymised male narrators, potentially comic situations with an unfolding atmosphere of unease, manual work and its contexts, inabilities to communicate or to approach conflict situations effectively, worry, self-doubt, small-mindedness, conflict developing as closed systems become entropic. In short, things falling apart.

Magnus Mills’ work – exemplified here by two short stories, and throughout the whole of Screwtop Thompson, and on into his work in novel format too – is characterised by its constraints: Englishness, routine, lack of information, anonymised male narrators, potentially comic situations with an unfolding atmosphere of unease, manual work and its contexts, inabilities to communicate or to approach conflict situations effectively, worry, self-doubt, small-mindedness, conflict developing as closed systems become entropic. In short, things falling apart.

As a reader, I find his approach fascinating, and both thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding. The work evidences control and technique, matching character with situation, and exploiting their in/abilities to communicate to tell a story which is at once ordinary and recognisable, yet strange and lingering. They’re like polite laughs in a tunnel – initially indicative of humour, but then warping and leaving you with an odd feeling that something not right has just happened which you can’t quite define.