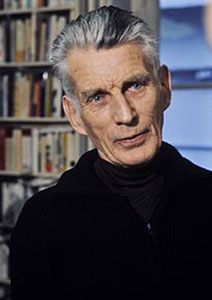

photo by Antonio Martinez

by K.S. Dearsley

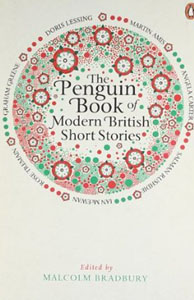

The first time I read Samuel Beckett’s ‘Ping’ I gave up halfway through. It was in The Penguin Book of Modern Short Stories and I couldn’t be bothered to try to interpret what seemed, at the time, to be gibberish. After all, stories were supposed to have a beginning, a middle and an end, weren’t they? Shouldn’t they have a narrator or at least a narrative, that is to say, a story?

It was only when I began studying linguistics at university that I decided to give ‘Ping’ another try. This time I found it to be a disturbing and compelling work by a master of his craft.

Beckett is perhaps best known for his innovative dramas such as Waiting for Godot and Not I, although he wrote short stories throughout his career. One of these, ‘Echo’s Bones’ created a stir when it was published by Faber & Faber 80 years after being rejected by his editor, Charles Prentice, and left out of his anthology More  Pricks than Kicks. Prentice called ‘Echo’s Bones’ a ‘nightmare’ and when I first picked up ‘Ping’ I felt pretty much the same way. But the trick to appreciating this story is a simple one…

Pricks than Kicks. Prentice called ‘Echo’s Bones’ a ‘nightmare’ and when I first picked up ‘Ping’ I felt pretty much the same way. But the trick to appreciating this story is a simple one…

Originally published in French in 1966, ‘Ping’ is very much a Modernist work. It attempts to represent consciousness, as it is experienced without an omniscient narrator intruding, hence the lack of a traditional form or story.

There is no context to help the reader decide whether the protagonist, or protagonists, are male or female, inside or outside; no answers to who, what, where, when, why. If you want concrete action and events you will be frustrated, but atmosphere, feeling, and emotion there is in abundance. Somehow, Beckett makes the reader feel what the ‘character’ feels. The story is akin to an Impressionist painting where a few dabs or dashes might indicate a figure. The artist knows it is a person with a head, two arms and two legs, but restricts him or herself to only painting the actual colours and shapes he or she sees.

Light heat white planes shining white bare white body fixed ping fixed elsewhere. Traces blurs signs no meaning light grey almost white. Bare white body fixed white on white invisible. Only the eyes only just light blue almost white.

There is a fashion for minimalism in writing at the moment. Poems are pared down to six words and stories are told in 140 characters. Beckett uses minimalism of a different kind. In ‘Ping’, he restricts his vocabulary to around 100 words, although the story is approximately 1,000 words long. There are no proper names and only one pronoun – ‘white walls each its trace’ – definite and indefinite articles are rare. Prepositional phrases and conjunctions are also scarce and the punctuation would give a strict grammarian apoplexy. In fact, some might question whether ‘Ping’ is a story at all, and not a prose poem. But ‘Ping’ is characterised by absence. However hard it might be to detect where or how, by the end of ‘Ping’ something has changed, and in my eyes that definitely makes it a story.

How does Beckett work this magic? Because the vocabulary is so limited, a large amount of repetition is used, with pairs of words recurring frequently so that a pattern emerges. This gives the phrases a cumulative effect, making them seem more significant. The repetition develops a rhythm, interrupted by the word ‘ping’. This feels like a signal of time up, or the return of a typewriter carriage, only to begin again. Both the pace and the feelings of tension and apprehension gain momentum as the sentences grow longer. What is about to happen draws closer, but you still cannot see it clearly.

Ping elsewhere always there but that known not. Ping perhaps not alone one second with image same time a little less dim eye black and white half closed long lashes imploring that much memory almost never. Afar flash of time all white all over all of old ping flash white walls shining white no trace eyes holes light blue almost white last colour ping white over. Ping fixed last elsewhere legs joined like sewn heels together right angle hands hanging palms front head haughty eyes white invisible fixed front over.

There is little doubt about the story’s power even if the critics disagree over what it is they have read. One claims it is about a dying man, another says it is about someone remembering a girl. Some feel the body and the consciousness Beckett writes about belong to the same person, others think they are two separate beings, not necessarily male or even human. Interpretation of the story changes with each reading. Because of this, I never tire of it.

There is little doubt about the story’s power even if the critics disagree over what it is they have read. One claims it is about a dying man, another says it is about someone remembering a girl. Some feel the body and the consciousness Beckett writes about belong to the same person, others think they are two separate beings, not necessarily male or even human. Interpretation of the story changes with each reading. Because of this, I never tire of it.

The best way to approach ‘Ping’ is to relax. Don’t struggle to interpret the story or work out what is happening, or to whom. Instead, simply read it, and when you have finished, start again. Let the words build an atmosphere and a sense of what might be there. You do not need to analyse the language or find a plot.

I may have initially thought of ‘Ping’ as a nightmare, but I am so glad that I went back to it and read it again… and again. Do the same and you may find, as I have, that you are haunted by the story’s ‘traces blurs signs’ and are drawn back to it at regular intervals. Maybe you will find ‘perhaps a meaning’. Ping over.