('Writer' © nivekhmng, 2011)

*

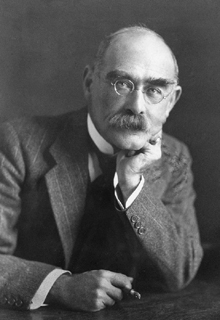

RUDYARD KIPLING AND THE CRAFT OF FABLE

by PROFESSOR CHARLES E. MAY

Much of the negative criticism that Rudyard Kipling’s fiction has received is precisely the same kind of criticism that has often been lodged against the short story form in general – for example, that it focuses only on episodes, that it is too concerned with technique, that it is too dependent on tricks, and that it often lacks a moral force.

American critic Edmund Wilson argued that Kipling’s appreciation for the episode prevented him from becoming a great novelist, ‘who must show us large social forces, or uncontrollable lines of destiny, or antagonistic impulses of the human spirit, struggling with one another’. But it is not simply because Kipling could not ‘graduate’, as it were, to the novel that critics have found fault with him. Frank O’Connor confesses his embarrassment in discussing Kipling’s stories in comparison with storytellers like Chekhov and Maupassant, for he feels that Kipling has too much consciousness of the individual reader as an audience who must be affected. C. S. Lewis accused that Kipling constantly shortened and honed his stories so much that they tended to be ‘continuously and obtrusively brilliant’ with no ‘leisurelines’. Such remarks indicate a failure to make generic distinctions between the nature of the novel and the nature of the short story; they either ignore, or fail to take seriously, Stevenson’s realisation that the tale form does not focus on character, but rather on fable, on the meaning of an episode in an ideal form.

I n the following discussion of two of Kipling’s best-known stories – ‘Mary Postgate’ and ‘The Gardener’ – I do not claim that the stories are not highly crafted, that they do not involve unrealistic character, that they do not depend on tricks. For in many ways, they must stand guilty of such charges. What I do wish to suggest is that such charges are not necessarily damaging, for they indicate that Kipling was perhaps the first English writer to embrace the characteristics of the short story form whole-heartedly, and that thus his stories are perfect representations of the transition point between the old-fashioned tale of the nineteenth century and the modern short story.

n the following discussion of two of Kipling’s best-known stories – ‘Mary Postgate’ and ‘The Gardener’ – I do not claim that the stories are not highly crafted, that they do not involve unrealistic character, that they do not depend on tricks. For in many ways, they must stand guilty of such charges. What I do wish to suggest is that such charges are not necessarily damaging, for they indicate that Kipling was perhaps the first English writer to embrace the characteristics of the short story form whole-heartedly, and that thus his stories are perfect representations of the transition point between the old-fashioned tale of the nineteenth century and the modern short story.

‘Mary Postgate’ has been singled as representative of many of Kipling’s shortcomings as an artist by critics who refuse to look at his short fictions as stories that exist in their own right, preferring instead to make moral judgments on Kipling himself. The story is set in World War I and centres around Mary Postgate, the companion of Miss Fowler and a surrogate mother to the latter’s nephew. The conclusion to the story, when Mary allows a fallen enemy pilot to die, is indeed a shocking one, but should be understood in terms of the character that Kipling creates. The most interesting aspect of the story is that it focuses on a character who is only known from the outside and who only exists in relation to other characters. As her mistress says to her at one point, “Mary, aren’t you anything except a companion? Would you ever have been anything except a companion?” Mary’s response is, “I don’t imagine I ever should. But I’ve no imagination, I’m afraid.”

However, it is precisely Mary’s imagination, an imagination that is never revealed to us until the shocking conclusion, that is the subject of the story. To Miss Fowler, Mary is but a companion; to young Wyndham Fowler – the orphaned nephew – she is an ‘unlovely’ ‘Gatepost’, ‘Postey’, or ‘Packthread’, his ‘butt and his slave’. When she cannot master the charts he brings home from the war, he says, “You look more or less like a human being … You must have had a brain at some time in your past … You haven’t the mental capacity of a white mouse.” Whatever Mary thinks of Wyndham is not directly revealed, for we never know what she thinks. “What do you ever think of, Mary?” Miss Fowler demands at one point. The reader can only guess.

And the only guess the reader can make is based on her reaction to news of Wyndham’s death. ‘The room was whirling round Mary Postgate, but she found herself quite steady in the midst of it.’ Passivity is indeed Mary’s primary characteristic, passivity and what Miss Fowler recognises as her ‘deadly methodical’ nature. Mary’s true imaginative relationship to Wyndham is indicated by her preparations to burn all of his things. The extremely long list of items that fills almost a page of text indicates, without sentimentalising, Mary’s devotion to Wyndham. But it is the death of the child in town by a bomb that more fully objectifies Mary’s relationship to the dead young man. After she sees the ripped and shredded body of the child, she uses Wyndham’s words about the enemy:

And the only guess the reader can make is based on her reaction to news of Wyndham’s death. ‘The room was whirling round Mary Postgate, but she found herself quite steady in the midst of it.’ Passivity is indeed Mary’s primary characteristic, passivity and what Miss Fowler recognises as her ‘deadly methodical’ nature. Mary’s true imaginative relationship to Wyndham is indicated by her preparations to burn all of his things. The extremely long list of items that fills almost a page of text indicates, without sentimentalising, Mary’s devotion to Wyndham. But it is the death of the child in town by a bomb that more fully objectifies Mary’s relationship to the dead young man. After she sees the ripped and shredded body of the child, she uses Wyndham’s words about the enemy:

‘“Bloody pagans! They are bloody pagans. But,” she continued, falling back on the teaching that had made her what she was, “one mustn’t let one’s mind dwell on these things.”’

By the time she reaches home the affair seems remote by its very monstrosity.

However, as she prepares the sacrificial oil to burn the remaining possessions of Wyndham, the image of both Wyndham and the child returns in the person of the downed enemy pilot. As the pilot asks for help, she cries, “Ich haben der todt Kinder gesehn.” And the dead child she has seen is of course not only the child in the village, but also the image of Wyndham, the only child, in her passivity, she has ever had. As the pilot cries for help, she screams, “Stop that, you bloody pagan” in Wyndham’s own words. Consequently, the pilot becomes not a human being, but a thing responsible for the death of Wyndham and the child in the village. As she hums and tends the fire, she thinks, ‘if it did not die before [tea-time] she would be soaked and have to change.’ Her primary characteristics of passivity and method serve her well here as she thinks with a secret thrill that she can be useful in the war effort. As she waits for the man to die:

…an increasing rapture laid hold on her. She ceased to think. She gave herself up to feel. Her long pleasure was broken by a sound that she had waited for in agony several times in her life.

When the sound of death does come, she says, “That’s all right,” just as she has said when she found out that Wyndham had fallen from four thousand feet. After she goes to the house and takes a luxurious hot bath before tea, Miss Fowler finds her relaxed on the sofa, looking “quite handsome!”

‘Mary Postgate’ is a tacit story of Mary’s hidden life in which she lives only in her imaginative relationship with others. What the story provides is the ironic single opportunity for Mary to act, by not acting, thus creating a bitter epiphany for the reader. Her secret thrill and final transfiguration result from her sense of being allowed to act in the world that she previously has only read about in the newspapers. The dropping of the pilot from the sky is like the magical breaking in of the external world into her previously hermetically-sealed world of passivity. It allows her to perform what she understands to be useful work in the world. The fantasy world becomes momentarily real and thus Mary finds a release for her previously unexpressed desires.

Like ‘Mary Postgate’, Kipling’s most famous story, ‘The Gardener’, also depends on concealment of an inner life for its effect and a split between external reality and a tenuous inner reality. The story follows a well-off single woman, Helen, as she raises a boy she claims is her nephew. The basic technique of the story depends on a gap between details that are ‘public property’, that is, details of which the village is aware and which in turn the reader knows, and unwritten details which are private property, known only to Helen herself. What is public is a lie and what is private is the truth; furthermore, what is ugly in the public eye is revealed as beautiful in the eye of the reader at the conclusion. The basic question is: what makes the truth beautiful at the end? Even at the end, Helen does not accept the young man as her son, still referring to him as her nephew, thus continuing the protective lie she has perpetuated throughout the story. The irony, however, lies in the fact that Helen’s heroism depends precisely on this concealment, for it is obviously done not for her own sake, but for her child’s.

Like ‘Mary Postgate’, Kipling’s most famous story, ‘The Gardener’, also depends on concealment of an inner life for its effect and a split between external reality and a tenuous inner reality. The story follows a well-off single woman, Helen, as she raises a boy she claims is her nephew. The basic technique of the story depends on a gap between details that are ‘public property’, that is, details of which the village is aware and which in turn the reader knows, and unwritten details which are private property, known only to Helen herself. What is public is a lie and what is private is the truth; furthermore, what is ugly in the public eye is revealed as beautiful in the eye of the reader at the conclusion. The basic question is: what makes the truth beautiful at the end? Even at the end, Helen does not accept the young man as her son, still referring to him as her nephew, thus continuing the protective lie she has perpetuated throughout the story. The irony, however, lies in the fact that Helen’s heroism depends precisely on this concealment, for it is obviously done not for her own sake, but for her child’s.

Earlier in the story, when the boy wants to call Helen ‘Mummy’, and she allows him to do so as their secret only at bedtime, she reveals the secret to her friends, telling the boy that it’s always best to tell the truth. His reply – “when the troof’s ugly I don’t think it’s nice” – constitutes a revealing irony in the story about the nature of truth and its relationship to beauty. What the boy calls ‘ugly’ is the truth Helen tells: that he call her ‘Mummy’ even though she is not his mother. The truth that she is his mother is however the beautiful truth that cannot be revealed within the profane realm of everyday society, for that truth would indeed be ugly from that profane point of view.

The death of the boy and his mysterious spontaneous burial under the shelled foundation of a barn marks the psychic death of Helen also, for in her double life, she truly has lived, like Mary Postgate, only for her son. The resurrection of his body marks a parallel resurrection for her as she makes her trip to visit the grave. Mrs Scarsworth, who is visiting a neighbouring cemetery and her secret lover’s grave, is, as other critics have well noted, an embodiment of Helen’s split self and thus echoes her previous position. Mrs Scarsworth tells Helen that she is tired of lying. “When I don’t tell lies I’ve got to act ’em and I’ve got to think ’em always. You don’t know what that means.” Helen of course knows precisely what that means, but even though she is the one most able to directly sympathise with Mrs Scarsworth, still she cannot tell the truth, for that truth is ugly within the profane world.

However, what is ugly to the profane world is finally revealed as beautiful within the realm of the sacred. Helen, who is both Mary Magdalene, the fallen, and Mary the mother of Christ, goes to find the grave of her son and saviour and is directed to it by the ultimate embodiment of the sacred. It seems inevitable, in a story that deals with a double life – the life of public property and the life of private emotion – that the ultimate incarnation of spirit within body in Western culture should be the means by which the secret of spirit is revealed to the reader. The secret revealed at the end of the story is the same as the one revealed when Mary comes to look for the body of Christ – that is, that he is not here, but has arisen – that is, that he is not body but spirit. The true reality of the story is the reality of the sacred and always hidden world, which is sacred precisely because of its hidden nature.

As is usually the case in short fiction, it is the world of spirit, the world of the sacred that constitutes the truth, and that truth, regardless of what it appears to be within the profane framework, is always beautiful. It is not so much that Kipling plays a supernatural trick at the end of the story, but rather that he needs an ultimate embodiment of spirit within body to communicate the ironic reversal of the apparent lie being the most profound truth. What Rudyard Kipling practiced so well was that the ‘not-told’ of the short story is more important than what is told, for what cannot be told directly always constitutes the ideal nature of story itself.

~

Charles E. May is Professor Emeritus at California State University, Long Beach. He is one of the leading literary scholars of the short story and has published numerous books on the subject including Edgar Allan Poe: A Study of the Short Fiction (1993), New Short Story Theories (1994), The Short Story: The Reality of Artifice (1995), and I Am Your Brother: Short Story Studies (2013). He writes the blog Reading the Short Story at www.may-on-the-short-story.blogspot.co.uk

Charles E. May is Professor Emeritus at California State University, Long Beach. He is one of the leading literary scholars of the short story and has published numerous books on the subject including Edgar Allan Poe: A Study of the Short Fiction (1993), New Short Story Theories (1994), The Short Story: The Reality of Artifice (1995), and I Am Your Brother: Short Story Studies (2013). He writes the blog Reading the Short Story at www.may-on-the-short-story.blogspot.co.uk