('Solitude' © Luca Rossato,2013)

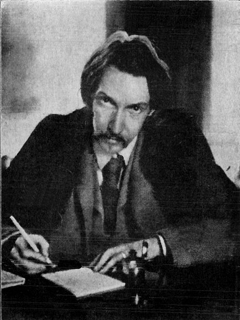

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON AND THE WELL-SPRINGS OF STORY

by PROFESSOR CHARLES E. MAY

It is no coincidence that Robert Louis Stevenson, the first British writer to be recognised as a specialist in the short story, was a champion of the romance form. Nor is it accidental that Stevenson’s interest in the short story made him one of the first British short-fiction writers to focus, as did Henry James, on technique and form rather than on content. In his essay, A Gossip on Romance (l882), Stevenson makes it clear that he wished to return to the well-springs of story, that is, to story for the sake of story, rather than story for the sake of character and conversation — the usual focus of the 19th-century novel.

As Stevenson describes it, the imagination perceives the world not as an end in itself, but as an opportunity for story; he notes, for example, how certain places fill one with the notion either that something has happened there or else something must happen there. The world becomes transformed into the stimulus for some hidden meaning that it is the artist’s job to lay bare, a task he performs by developing some incident that seems appropriate to the feeling and the place. Stevenson says that although the stories of the great creative writers may be nourished with the realities of life, ‘their true mark is to satisfy the nameless longings of the reader, and to obey the ideal laws of the day-dream’. This focus on the transformation of ideal laws of the imagination into an as-if real incident leads Stevenson to understand story in much the way that Poe and Henry James did; that is, that fiction objectifies the basic human desire that life have the unity and meaning of narrative and that all circumstances in a narrative must come together like a painting.

Stevenson knew that English readers in the latter part of the l880s were ‘apt to look somewhat down on incident, and reserve their admiration for the clink of teaspoons and the accents of the curate’, as if indeed such detail of everyday life constituted the only reality. However, there is another reality, says Stevenson, the reality of imagination and play; indeed, argues Stevenson, fiction is to the grown man what play is to the child. Such a point of view was not particularly palatable to the temperament of the late 19th-century British reader, who insisted that there must be either moral earnestness or else minute realistic detail in fiction for it to have any value.

Stevenson continued his discussion on the nature of narrative in l884 when he joined his own voice to the debate about the art of fiction then going on between Walter Besant and Henry James. Taking the side of James, Stevenson insisted that technique rather than content was the basis for narrative as an art form, suggesting a notion that has since been developed to significant theoretical lengths by the Russian Formalist critics of the 1920s — that is, if we wish to understand the secret of art, we must not focus on its similarities to external reality, but rather on its basic differences — the distance from life that technique and form create. The whole secret, says Stevenson, is that artworks do not compete with life, but rather like ‘arithmetic and geometry, turn away their eyes from the gross, coloured and mobile nature at our feet, and regard instead a certain figmentary abstraction’.

Stevenson continued his discussion on the nature of narrative in l884 when he joined his own voice to the debate about the art of fiction then going on between Walter Besant and Henry James. Taking the side of James, Stevenson insisted that technique rather than content was the basis for narrative as an art form, suggesting a notion that has since been developed to significant theoretical lengths by the Russian Formalist critics of the 1920s — that is, if we wish to understand the secret of art, we must not focus on its similarities to external reality, but rather on its basic differences — the distance from life that technique and form create. The whole secret, says Stevenson, is that artworks do not compete with life, but rather like ‘arithmetic and geometry, turn away their eyes from the gross, coloured and mobile nature at our feet, and regard instead a certain figmentary abstraction’.

Narrative flees from external reality and pursues ‘an independent and creative aim’, urges Stevenson.

So far as it imitates at all, it imitates not life but speech: not the facts of human destiny, but the emphasis and the suppressions with which the human actor tells of them.

Stevenson makes an important point here, suggesting that story writing actually imitates story telling — that its source is in language, the narrative impulse, and what it depicts is not reality but the perception of reality made by one in the process of making a story. For Stevenson the work of art exists then not by its resemblance to life, ‘but by its immeasurable difference from life, which is designed and significant, and is both the method and the meaning of the work’. Such a self-conscious awareness that story, while bound to incident, is the formal embodiment of daydream and the process of story itself, was essential before the modern short story could become possible.

‘A Lodging for the Night’ is a strange candidate for a landmark story that marks the shift to modern short fiction. The story takes place on a winter night in 1456 when the great poet Francis Villon wanders the streets of Paris trying to escape the French police. He is robbed, steals money from the body of a dead prostitute, and is denied refuge by those with whom he has formerly been related, until an old soldier takes him in for food, drink, and conversation. Although it is highly detailed and focuses on a specific time-limited situation, it poses more questions about its generic status than clear answers. There is no doubt that ‘A Lodging for the Night’ is filled with hate and horror, but the interesting question is why it is not a hateful and horrifying story overall. The key to this irony is the character of Villon himself and his basic situation. Although the reader may have a conventional expectation that a poet’s life should not be focused on practical existence, the structure of the story challenges this expectation. The basic irony of the story is that it is a tale about a poet whose primary concern is practical existence. As the narrator of the story suggests, ‘In many ways, an artistic nature unfits a man for practical existence’.

One might legitimately wonder what is the point of a story about an artist who does not act like an artist. This question raises the central issue of the story, that is, the challenge to our conventional expectation of what an artistic nature actually is. To examine this issue, one need not go outside the story to refer to the life of the real Villon, except to note that Stevenson chose him because of his known vagabond existence. Such a figure offers Stevenson the opportunity to examine in a single incident the hypothesis that an artist’s focus on survival has nothing to do with his art.

Villon’s only concern in the tale is with life and therefore inevitably with death. However, in the beginning of the story, he mocks death by mocking the sound of the wind blowing through the gibbet as he jokes that they are ‘all dancing the devil’s jig on nothing up there’. After one of the men has been stabbed, Villon laughs bitterly, as though ‘he would shake himself to pieces’. He then says they will all be hanged and puts out his tongue and throws his head to one side to counterfeit the appearances of one who has been hanged. After he leaves and tries to find some shelter from the cold and the patrol, he stumbles over something both hard and soft, firm and loose, and gives a little laugh when he discovers it is the body of a dead prostitute. He indeed makes an emotional response to this discovery later, but only after he takes the two coins from her stocking and wonders at the ‘dark and pitiable mystery’ that she should have died before she could spend the money. Villon himself thinks, ‘He would like to use all his tallow before the light was blown out and the lantern broken.’

Villon goes to his spiritual father but is driven away; he goes to his physical mother and has slop dumped on him. After the first rebuff, the humour of the situation strikes him and he laughs. After his mother rebuffs him, he thinks of taking a lodging and being fed many favourite delicacies. When he thinks of ‘roast fish’ – the subject of the ballad he had been writing when the murder took place – the phrase fills him with ‘an odd mixture of amusement and horror’. Indeed, this combination might well summarise the mood of the story itself, for in a strange way it fills the reader with just the same mixture.

Villon goes to his spiritual father but is driven away; he goes to his physical mother and has slop dumped on him. After the first rebuff, the humour of the situation strikes him and he laughs. After his mother rebuffs him, he thinks of taking a lodging and being fed many favourite delicacies. When he thinks of ‘roast fish’ – the subject of the ballad he had been writing when the murder took place – the phrase fills him with ‘an odd mixture of amusement and horror’. Indeed, this combination might well summarise the mood of the story itself, for in a strange way it fills the reader with just the same mixture.

When Villon enters the house of the old soldier, the ambiguous mixture of amusement and horror becomes more obvious. Whereas the old man takes their little debate seriously, Villon primarily uses it to stall, to allow more time for protection from the cold and to eat and drink the old man’s food. Point by point, Villon gets the old man to admit that in many ways there is no difference between a soldier and a thief, except that the soldier is a greater thief because he is allowed to take more. Villon becomes quite comfortable as the old man cannot decide to drive him out or to convert him. He admits there is something more than he can understand in all of Villon’s talk, but that he is convinced that Villon is one who has lost his way and made an error in life.

You are attending to the little wants, and you have totally forgotten the great and only real ones […] For such things as honor and love and faith are not only nobler than food and drink, but indeed I think we desire them more, and suffer more sharply for their absence.

Villon then delivers his own little sermon about his honour which he says he keeps in a box until it is needed. He notes that he has had the opportunity of killing and robbing the old man but has resisted out of a sense of honour. When the old man throws him out, Villon goes out to meet the dawn, having indeed found a lodging for the night, thinking: ‘A very dull old gentleman … I wonder what his goblets may be worth.’

The secret of the story’s ambiguous mixture of horror and amusement depends solely on the nature of the poet Villon, who alternates between attending to the immediate concerns of life to assure his own preservation and taking an amused and distant view of reality. Villon survives not only because of his concern with immediate things, but also because he can take such an ironic view of life and death. The murdered man and the dead prostitute take on a curious unreality to him, except for such details as the man’s red hair and the prostitute’s two unspent coins. Otherwise they do not impinge on Villon except to remind him that he may meet the same fate unless he finds lodging for the night. The final irony is of course that it is his scholarly and poetic nature which saves him, for only by engaging in debate with the old man is he allowed to stay in safety until dawn. Thus the two basic elements of the story – artistic nature and practical existence – are seen to be less incompatible than they first seem. Indeed, it is both Villon’s poetic nature and his concern for immediate survival that save him. The secret of the poetic nature lies in its ability to distance itself from life and death, to mock it, to transform it into the source of art.

Rather than focusing on form because he had little content of value to communicate, as some previous critics have claimed, Stevenson, like Henry James, is primarily concerned with the structure and essential nature of fiction itself. It is Stevenson’s acute self-consciousness of the significance of structure and the problem of presenting psychic reality as if it were externally manifested that makes critics refer to him as the first ‘modern’ short-story writer in British fiction.

~