Photo by Gilderic

Article by Paul Curd

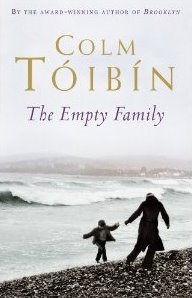

In his first book since the pitch-perfect Brooklyn, Colm Toibin once more examines the great Irish theme of exile and homecoming in his new collection of short stories, The Empty Family. As the title suggests, many of the stories also revolve around family relationships, and their sweet and sour nature.

In the first story ‘One Minus One’, for example, the narrator is exiled in Texas and thinking of his mother ‘six years dead tonight’. The story is addressed to the narrator’s ex-lover in Ireland. The bitter memories of his mother’s death, and the narrator’s return to Ireland for her funeral, are also tinged with regret at the loss of this other relationship. And yet when the narrator realizes it is ‘too late now, too late for everything’ he does so ‘almost with a sense of relief’.

This opening story sets the tone. In the title story ‘The Empty Family’, a partner piece to ‘One Minus One’, the narrator again returns to Ireland from America and is filled with regrets for his lost lover. Here, Toibin uses the device of a telescope as a metaphor for the relationship between time and one-eyed memories.

‘Silence’ reintroduces us to some familiar Toibin characters. The story’s protagonist, Augusta Gregory, was the real-life muse to W B Yeats and the subject of Toibin’s 2002 essay Lady Gregory’s Toothbrush. The story itself springs from an extract from the notebooks of Henry James, the subject of his 2004 Booker-shortlisted novel The Master, but given a subtle twist by Toibin.

In ‘The Two Women’ an aging movie set-dresser returns to Ireland from America to work on a film, longing to be home before she arrives and becoming instantly miserable on her arrival in what seems like alien territory. Her time back home gives occasion for recollections of the great love of her live, recollections that are given added poignancy by an unexpected encounter on the film set in Wicklow.

There’s a lot of graphic gay sex in a number of these stories, but often there’s a point to it in the context of the story. In ‘The Pearl Fishers’ Toibin uses the famous duet from the Bizet opera as the inspiration for this tale of triangular love and friendship, with the twist that the friends are also the lovers. The scenes set in a Wexford boarding school leave little to the imagination but are a key element in the plot. Similarly, the relationship that develops between two of the characters in the long final story ‘The Street’ has a necessary physical element that Toibin handles well.

‘Barcelona, 1975’ is a story about gay sex that doesn’t work quite so well. It reads like a rather self indulgent piece of confessional autobiography, with some detailed descriptions of all-male sex (including group sex) but no depth or finesse in comparison with most of the other stories in this collection. It is, perhaps, the weak link in an otherwise strong narrative chain.

In contrast, the allegorical story ‘The New Spain’ has a depth in both character and theme that is much more in keeping with a writer of Toibin’s quality. In this tale, an exiled daughter returns to post-Franco Spain after the death of her grandmother (and three years after the death of the dictator) to establish a new order in her family.

In contrast, the allegorical story ‘The New Spain’ has a depth in both character and theme that is much more in keeping with a writer of Toibin’s quality. In this tale, an exiled daughter returns to post-Franco Spain after the death of her grandmother (and three years after the death of the dictator) to establish a new order in her family.

This collection of short stories is beautifully written and each story is full of atmosphere, often with Toibin’s typical sense of loss and longing, of ‘sad echoes and dim feelings’. Toibin is strongest when he is exploring the complexity of family relationships, and the bitter-sweet sense of nostalgia for the ‘home’ that his protagonists usually had a good reason to leave. It is perhaps because many of these stories dwell on that familiar mix of emotions that this collection works so well.