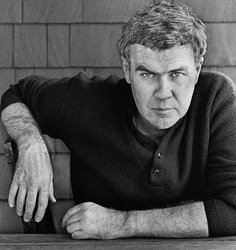

Photo by Silva M. Kinzelmann

by Wendy Good

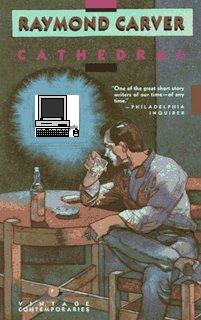

It is the contradictions of the human condition which Raymond Carver is so adept at exploring, a quality that makes his 1983 collection Cathedral a captivating read. The unexpected fusion of his characters’ prejudices and vulnerability, along with Carver’s minimalistic style, draw the reader more and more deeply into his stories of apparently ordinary American lives. Jonathan Yardley of the Washington Post describes Carver as: ‘a writer of astonishing compassion and honesty, utterly free of pretense and affectation…set only on describing and revealing the world as he sees it.’ It is this revelatory power and Carver’s expert control of timing that make the best of his stories unforgettable.

One of the most striking stories in this collection is ‘A Small, Good Thing’. The plot revolves around a misunderstanding about a birthday cake being left, unpaid for, at a bakery by a mother, after her son, Scotty, is hit by a car on his birthday. Carver thrives on the idea of failed communication in this story and others; in an interview in 1987 with Claude Grimal, Carver explained how he was interested in ‘dialogue between people who aren’t listening to each other.’ The cacophony Carver builds from the misunderstandings in ‘A Small, Good Thing’ is developed through a series of ever more unsettling nuisance calls from the baker to the family. We hear it, too, in the parents’ confusion at the hospital where Carver repeats trigger words, such as ‘operate’, to convey agitation, stress and a sense of disconnection.

One of the most striking stories in this collection is ‘A Small, Good Thing’. The plot revolves around a misunderstanding about a birthday cake being left, unpaid for, at a bakery by a mother, after her son, Scotty, is hit by a car on his birthday. Carver thrives on the idea of failed communication in this story and others; in an interview in 1987 with Claude Grimal, Carver explained how he was interested in ‘dialogue between people who aren’t listening to each other.’ The cacophony Carver builds from the misunderstandings in ‘A Small, Good Thing’ is developed through a series of ever more unsettling nuisance calls from the baker to the family. We hear it, too, in the parents’ confusion at the hospital where Carver repeats trigger words, such as ‘operate’, to convey agitation, stress and a sense of disconnection.

Carver amplifies the sense of misunderstandings and misinterpretation, above all in the mother’s reactions to the baker, whom she disliked at first sight: ‘The baker was not jolly. There were no pleasantries between them, just the minimum exchange of words, the necessary information. He made her feel uncomfortable, and she didn’t like that’. In contrast, the doctor at the hospital is described as handsome, big shouldered and tanned. He is someone to trust in a crisis. By the end of the story, though, Carver switches these presuppositions of character. The doctor will disappoint. The baker will bring comfort.

Carver’s use of dramatic tension is subtle. The story is not driven solely by action; indeed, the revelation that Scotty has been hit by a car is restrained, even anti-climactic. The most horrifying spectacle comes in the phone call from the baker, supposedly to remind the mother about the cake that awaits collection: ‘‘Your Scotty, I got him ready for you,’ the man’s voice said. ‘Did you forget him?’’ The moment is full of menace and ambiguity.

Like all great story writers, Carver appreciates how movement — the life of the body — is vital for conveying human emotion. He shows an insight into the parents’ anxiety by describing how they move: ‘His leg began to tremble’; ‘She was afraid, and her teeth began to chatter until she tightened her jaws.’

What is particularly intriguing about this story is Carver’s use of food as a cultural object. Not only is Scotty’s birthday cake a sign of a celebratory event, but the baker’s sharing of his food at the end of the story is a sign of reparation. Food, here, almost takes on the redeeming power of a religious sacrament – that of the breaking of bread. He touches upon an act which has a timeless quality and a quiet resolve. Carver also draws upon the social interactions behind food and nourishment to structure his story. He starts with the excitement of the child’s birthday cake, ‘a space ship and launching pad under a sprinkling of white stars…’ and finishes at the other end of the spectrum, food to comfort the grieving, or as the baker describes it: ‘Eating is a small, good thing in a time like this’.

It is his poignant style that makes this, and every story in the collection, a powerful read. We feel it in the moment the baker offers the grieving couple food, in the moment he calls the house, and in the moment the father embraces his dead son’s bicycle: ‘He dropped the box and sat down on the pavement beside the bicycle. He took hold of the bicycle awkwardly so that it leaned against his chest. He held it, the rubber pedal sticking into his chest. He gave the wheel a turn.’ Carver sharpens his stories to the point where a simple action or object becomes loaded with the feeling of elation or despair.

Arguably, ‘A Small, Good Thing’ is the most traumatic story within Cathedral. It haunts the reader, with a quiet ending and a sense of aftermath that both moves and troubles us long after the final line.