('Americana' © Shelby Bell, 2015)

PEOPLE ARE STRANGE: THE DARK TALES OF FLANNERY O’CONNOR

by JUDY UPTON

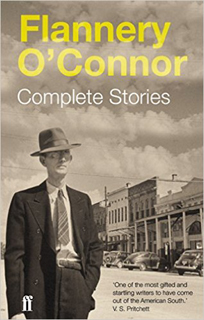

The short story collection I’d recommend above all others is Flannery O’Connor, the Complete Stories.

O’Connor was born is Savannah, Georgia in 1925. Her stories are quirky, vivid and so original that they don’t date, and she uses them to illuminate aspects of the human condition with a wry, surprising and, at times, startling tone. O’Connor explores foibles and obsessions with a gleeful relish, presenting us with a cast of eccentric loners, religious zealous, cunning deceivers, and painfully mismatched odd couples. She creates atmospheres of brooding menace, of petty social snobbery, and moral vacuum, always in the small towns and isolated farmsteads of the American Deep South. Her understanding of the human condition makes it difficult to believe that the first of her stories in this collection was published when she was only twenty-one.

I first discovered O’Connor when I was going through a phase of reading authors and dramatists from the southern states of the US, including William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers. Like McCullers, O’Connor skilfully depicts three-dimensional, strong-minded southern women, sometimes wise, sometimes misguided but always unforgettable – Mrs Freeman, for example, in ‘Good Country People’:

Besides the neutral expression that she wore when she was alone, Mrs. Freeman had two others, forward and reverse, that she used for all her human dealings. Her forward expression was steady and driving like the advance of a heavy truck. Her eyes never swerved to left or right but turned as the story turned as if they followed a yellow line down the center of it. She seldom used the other expression because it was not often necessary for her to retract a statement, but when she did, her face came to a complete stop, there was an almost imperceptible movement of her black eyes, during which they seemed to be receding, and then the observer would see that Mrs Freeman, though she might stand there as real as several grain sacks thrown on top of each other, was no longer there in spirit.

I work as a playwright and screenwriter, and the lessons I’ve taken from O’Connor’s short stories are to create a memorable opening and constantly surprising characters, while keeping the narrative at all times both logical and believable. The opening of ‘The Heart of the Park’ makes the reader immediately start to wonder what on earth is to come:

Enoch Emery knew when he woke up that today the person he could show it to was going to come. He knew by his blood. He had wise blood like his daddy. At two o’clock that afternoon, he greeted the second-shift gate guard. “You ain’t but only fifteen minutes late,” he said irritably.

If she was around today, I feel sure O’Connor would be writing for both film and TV. Her way of seeing the world and the ability of her stories to mix comedy, tragedy, satire and horror, are similar in sensibility to the screenplays of the Coen Brothers. Sadly, as yet, only O’Connor’s first novel, Wise Blood, has been made into a film. It was shot by the legendary director John Huston but not made until 1979, long after her untimely death. When Flannery O’Connor died of lupus in 1964, it was a significant literary life cut tragically short. If she had lived beyond her thirties and beyond I believe she would be a household name today alongside American authors such as John Steinbeck and William Faulkner.

If she was around today, I feel sure O’Connor would be writing for both film and TV. Her way of seeing the world and the ability of her stories to mix comedy, tragedy, satire and horror, are similar in sensibility to the screenplays of the Coen Brothers. Sadly, as yet, only O’Connor’s first novel, Wise Blood, has been made into a film. It was shot by the legendary director John Huston but not made until 1979, long after her untimely death. When Flannery O’Connor died of lupus in 1964, it was a significant literary life cut tragically short. If she had lived beyond her thirties and beyond I believe she would be a household name today alongside American authors such as John Steinbeck and William Faulkner.

Everything in a Flannery O’Connor story is heightened and slightly miraculous. She has the knack of crafting the extraordinary from the ordinary and can, to an extent, be seen as working in the Southern Gothic tradition. She also has the skill of creating a great title that makes you yearn to read the story: ‘A Good Man Is Hard To Find’, ‘You Can’t be any Poorer Than Dead’, ‘Everything That Rises Must Converge’, ‘Enoch and the Gorilla’.

My personal favourites among her short stories include ‘Good Country People’, in which a young woman with an artificial leg attempts to seduce a man who is travelling through the area. She is a beautifully drawn character. Aged thirty-two, overweight and with a Ph.D in philosophy, she has changed her name from Joy to Hulga to almost revel in her own ungainliness, as well as to spite her mother. When a young Bible salesman comes calling, Hulga is certain that she will be his seducer. She only wants to use this traveller to finally experience sex and has no emotional feelings for him whatsoever. However, when the couple head for the hayloft, she has failed to consider that this man might harbour a concealed motive of his own. It is only when he has stolen away with her artificial leg, leaving her trapped in the hayloft, that she realises that it is after all she who has been seduced and tricked by the trophy hunter. I love the unexpected ending and the fact that although O’Connor has created an iron-willed, distinctly unconventional heroine, she is unafraid to leave her unexpectedly the loser in the narrative.

When all of him had passed but his head, he turned and regarded her with a look that no longer had any admiration in it. “I’ve gotten a lot of interesting things,” he said. “One time I got a woman’s glass eye this way. And you needn’t to think you’ll catch me because Pointer ain’t really my name. I use a different name at every house I call at and don’t stay nowhere long. And I’ll tell you another thing, Hulga,” he said, using the name as if he didn’t think much of it, “You ain’t so smart. I been believing in nothing ever since I was born!”

I had this story in mind when I wrote my own short play Undone, in which a young woman recently cured of button phobia invites a man back to her place, but her desires are actually focused around his buttons rather than him.

Another stand out O’Connor story that has a timeless or contemporary quality, and deals with obsessions, is ‘Parker’s Back’. A man who has always used his tattoos to impress women ends up falling for and marrying the only woman unmoved by them. In a last ditch attempt to win her over, he embarks on getting a very painful full back tattoo of the face of God. He assumes this will deeply impress his very religious, pregnant wife. Again the result is both tragi-comic and unexpected:

Another stand out O’Connor story that has a timeless or contemporary quality, and deals with obsessions, is ‘Parker’s Back’. A man who has always used his tattoos to impress women ends up falling for and marrying the only woman unmoved by them. In a last ditch attempt to win her over, he embarks on getting a very painful full back tattoo of the face of God. He assumes this will deeply impress his very religious, pregnant wife. Again the result is both tragi-comic and unexpected:

“God? God don’t look like that!”

“What do you know how he looks?” Parker moaned. “You ain’t seen him.”

“He don’t look,” Sarah Ruth said. “He’s a spirit. No man shall see his face.”

“Aw listen,” Parker groaned, “this is just a picture of him.”

“Idolatry!” Sarah Ruth screamed. “Idolatry!”

In ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’, a garrulous and self-righteous grandmother has a philosophical conversation with an escaped murderer known as ‘The Misfit’, while his companions are murdering her family in the woods. As is usual in O’Connor’s stories, she gives her characters lines that are truly unforgettable. “She would have been a good woman,” the misfit muses towards the end of the story, “If it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

Flannery O’Connor’s The Complete Stories is a book I go back to time and time again, and the tales always feel fresh, still make me smile, gasp or think hard about some aspect of modern life. I can’t think of another author, apart from perhaps Colette, whose stories I find so consistently inviting.

~

Chichester University graduate Judy Upton works as a playwright and screenwriter, having won the George Devine,Verity Bargate and Croydon International Awards for playwriting. Her plays have been produced by the Royal Court, National Theatre, Birmingham Rep, Durham Gala and BBC Radio 4 among others. She has had an original TV drama shown on BBC1 two feature films produced. Judy has also had a number of short stories published.

Chichester University graduate Judy Upton works as a playwright and screenwriter, having won the George Devine,Verity Bargate and Croydon International Awards for playwriting. Her plays have been produced by the Royal Court, National Theatre, Birmingham Rep, Durham Gala and BBC Radio 4 among others. She has had an original TV drama shown on BBC1 two feature films produced. Judy has also had a number of short stories published.