photo by Al Cooper

by Vicki Heath

As we all know, a writer can learn a lot from reading short stories. We can learn to craft dialogue, to open in medias res, to keep our readers guessing, to end on a bang, to end on a whisper. It’s great to collect all these nuggets and to practice them, but, let’s be honest, publication is probably at the back of most writers’ minds. So when one reads an anthology that collects the winning stories of a prize or award, it’s the perfect time to learn what the judges of that award might be looking for in its winning entries. After all, every short story journal and literary magazine out there tells us: read a copy before you submit.

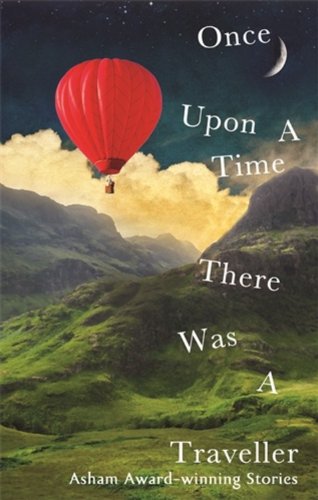

The Asham Award is a short story competition for new female writers (sorry gents). It was set up in 1997, in memory of Virginia Woolf, and every other year the Asham Literary Endowment Trust and Virago Press produce an anthology of the winning stories. Once Upon a Time There Was a Traveller is the 2013 compilation and includes the works of twelve new writers, alongside stories from Susie Boyt, Helen Dunmore and Angela Carter. It’s a gripping assembly of inventive interpretations of the theme ‘travel’, with everything from holiday preparations, and a deserted airport, to travelling through a lifetime, and the journey of an obsession.

As I read, I considered each story carefully, wondering what made these particular pieces stand out for the judges – Lennie Goodings, Sara Wheeler and Helen Dunmore. Some appealing elements were easy to see. What’s not to love about a story intriguingly entitled ‘The Elephant in the Suitcase’? But Deepa Anappara’s story, which won third prize, goes far deeper than an amusing title and has a lot to teach us about describing a fragile mind. The story tells of a forest guard, named Nirmal, who looks to the forest for signs about his life, after the howling of a pair of wood owls hails his mother’s death.  So when an elephant starts hounding him, trying to rip his home apart, Nirmal is understandably perturbed. The story has a soft humour running through it, as Nirmal’s paranoia about his elephant stalker emerges and his colleague doesn’t believe him: “Oh, I see, so I’m making it all up, eh? That’s just great. And the best I could come up with was an angry elephant? Not even a bloody ghost?”

So when an elephant starts hounding him, trying to rip his home apart, Nirmal is understandably perturbed. The story has a soft humour running through it, as Nirmal’s paranoia about his elephant stalker emerges and his colleague doesn’t believe him: “Oh, I see, so I’m making it all up, eh? That’s just great. And the best I could come up with was an angry elephant? Not even a bloody ghost?”

As the story progresses, Nirmal begins to feel his age and decides to leave the forest to be with his wife and daughter, and to take on a mundane job. He is filled with apprehension as he leaves, that is, until the elephant reappears and charges him, confirming his need to go. This culmination of events may well be real, or it could be imagined by Nirmal – Anappara leaves us to decide – but either way, he knows it is time to leave the forest and return to his family.

Within this turmoil, Anappara’s use of small, yet rich detail paints a beautifully vivid scene. There were shutters that ‘hung loose like broken elbows’, fungi were described as ‘chocolate saucers’, and Nirmal himself is beautifully juxtaposed against the forest background: ‘He touched the bald patches on his head and thought of the receding treeline of the forest.’

This use of small detailing runs through many of the stories in the collection. Pippa Gough’s winning story, ‘The Journey to the Brothers’ Farm’, sets a South African scene with rich minutiae: ‘waking to the rustling and creaking of the grass roof heating up in the early morning sun’. In Helen Dunmore’s specially written story, ‘Duty-Free’, the location is instantly set through the use of everyday souvenirs. As soon as we see ‘a display of silver leprechauns’ there’s no question that we’re in an Irish airport.

Lynn Kramer’s story ‘Legs’ uses the everyday particularly well, through the observations of a little girl. As Anna and her mother wait for the bus to take them to the doctor’s, Anna wriggles her fingers around in her mother’s hand, so that she can ‘feel the shape of the wedding and engagement rings through her mother’s cotton glove’. This is something I remember doing with my grandma’s wedding bands when I was a young child. I hadn’t thought of it since, until I read Kramer’s words and this small personal detail brought an instantly nostalgic feeling to the story. A little later, Anna examines the reflections of her and her mother in a restaurant window, as they wait for the bus:

Her mother’s straw hat at the top, then her navy-blue, button-through dress, and then her legs going on right to the bottom of the glass. Next to her, halfway down, was Anna’s pink blouse with the puff sleeves, and her grey pleated skirt, and legs which looked like pick-up sticks, except that legs were supposed to hold you up and pick-up sticks just fell down.

It’s a gentle, childlike observation that captures the pair of them vividly. Both are dressed primly and that ‘button-through dress’ instantly seems stiff and prudish, yet from a child’s perspective the description is harmless enough. We soon see that the mother is a pushy type, wanting her daughter to be a ‘famous ballerina’, but Anna has recently been bedridden, unable to dance. We gradually discover that Anna made up the pain in her legs that was keeping her in bed. At the end of the story, we see the mother’s absolute frustration and heartache, as the image of the gloves is used once more:

She slid her gloves back on, pressing them down between her fingers. “He wants to talk to you about why you couldn’t walk. Because the hospital says that every single one of those tests is completely normal.” She tore the gloves off and struck them against the ostrich bag. “It’s proof, Anna. It’s proof there is nothing wrong with you.”

Though the mother doesn’t understand her daughter’s actions, the reader can see – the moment has been building since the ‘button-through dress’. Kramer leaves us with the mother’s berating words and Anna longing for a glimpse of the lighthouse, ‘shining like a castle in the sea’. We understand that all she wants is to be a child.

Unlike this balanced and affecting story of childhood, many of the tales within Once Upon a Time challenge our initial preconceptions of the main characters. ‘Where Life Takes You’ by Dolores Pinto – the second prize winner – portrays a woman who has moved to Whitby to be with her new boyfriend. Initially, she seems snooty and paranoid, thinking the whole town is against her. But by the end of the story it is clear that she is struggling with a deepset grief. In ‘School Run’ by Kate Marsh, a girl falls in love with a boy and we follow the journey of their life together. At school and college, her friends don’t understand her relationship with this overly studious man; they prefer the jocks. But as time passes her friends’ perceptions change, and her husband’s geeky ways ultimately become cool.

The final story in the anthology, Angela Carter’s ‘The Magic Toyshop’, challenges not only the reader’s preconceptions, but the protagonist’s too. Three children have recently been orphaned and are to leave their home in the country to live with their Uncle Philip in London. Uncle Philip, we learn, used to be a toy maker and this occupation instantly creates a stereotyped idea of his appearance in the reader’s mind. The eldest of the children, Melanie, imagines Uncle Philip to be ‘an old man in a cowboy hat with a black and white photograph face’. When Melanie and the children arrive at the London station, they are greeted by two very different men, ‘country people in a sense that Melanie was not’. The man who appears to be her uncle is ‘clumsily assembled’, with ‘a half-smoked cigarette, disintegrating into rags of paper and shreds of tobacco, tucked behind his ear’. And when he walks to meet Melanie, Carter draws out every shred of his ungainliness:

…a tower falling, a frightening, uncoordinated progression in which he seemed to crash forward uncontrollably at each stride, jerking himself stiffly upright and swaying for a moment on his heels before the next toppling step.

Can you imagine this man making toys? Melanie certainly can’t and images of ‘men who haunted main-line London railway stations to procure young girls for immoral purposes’ run through her mind. The man, however, knows her name and therefore must be her Uncle Philip, once toy maker.

The Asham anthology has taught me a lot, both about writing short stories and what the judges might have looked for in a submission. Almost all of the pieces in the collection are peppered with rich detail. Many of the stories take our preconceptions and turn them on their heads. While others travel deep into the human mind, exposing fear and paranoia. There wasn’t a huge amount of humour in the anthology, certainly no belly laughs, but a gentle wit could be found in several of the stories. There weren’t any overly fantastic themes to the stories, though some of them touched on the surreal. Neither was there any kind of genre fiction. It’s all purely literary, dealing with some difficult topics, including an affecting tale about an alcoholic mother – ‘Pay Day’ by Dawn Nicholson. Individually, I can see why every story in there was chosen and perhaps, by looking closely, this reading might help my chances of submitting in the future. Who knows? At the very least, I’ve been reminded just how important the simple observations of daily life can be in any short story.

~

To find out a little more about the Asham Award, read Carole Buchan’s feature on ‘New Writers With Their Sights Set On Fame’ on Thresholds.