(GW Statue © Brook Ward, 2017)

NOT ABOUT NIGHTINGALES: THE FAIRY TALES OF OSCAR WILDE

by LOUISE MURRAY

One of Tennessee Williams’ lesser known pieces is a short, three-act play called Not About Nightingales. The story concerns the romance between a bitter, handsome con and the secretary of the prison warden. Jim, the con, is an aspiring writer; he wants to write, he tells Eva, the wide-eyed secretary, but it won’t be “sissy stuff” or “verbal embroidery”. Shunning Keats and ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, he will not “smother himself in lilies”. Instead, he will “blow things wide open”. His own work will be “not about nightingales”.

That phrase, not about nightingales, has always intrigued me. What it encapsulates is the notion that life, and good art, is definitively not about fripperies; while the kind of art that is glib, grandiose, and embroidered with falsehood very much is. Perhaps, then, Jim would find the fairy tales of Oscar Wilde too much about nightingales, but I would disagree. Look beneath the surface and simplicity of the narrative, and the reader will find concealed there a deep complexity which complements the ornateness of prose – a complexity of morality, of feeling and of soul.

Oscar  Wilde published two collections of fairy tales: The Happy Prince and Other Stories in 1888, and A House of Pomegranates in 1891. All in all, these two volumes include nine literary fairy tales, which are often collected, read, and understood together.

Wilde published two collections of fairy tales: The Happy Prince and Other Stories in 1888, and A House of Pomegranates in 1891. All in all, these two volumes include nine literary fairy tales, which are often collected, read, and understood together.

The first collection contains the title story ‘The Happy Prince’ which is a gorgeously maudlin tale. In it, the statue of the Happy Prince bids his devoted friend, the sparrow, to strip him of his gold leaf and jewels and to give these riches to the wretched poor of the city. From his perch high above the fray, the Happy Prince is doomed to be the all-seeing eye, and his heart, although it is made of lead, cannot bear the hardship he is forced to witness. In the story of ‘The Selfish Giant’, the Giant shuts out the children who wish to play in his beautiful garden, and brings an eternal winter upon himself as punishment for his selfishness. When he finally allows the children in to play, having seen the error of his ways, spring returns in an abundance of white blossom and the Giant watches joy bloom in his garden. In ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’ a student desires a red rose for his beloved, and the noble little nightingale fashions one from her own bleeding heart and the song of her death. But when the student presents the priceless rose to his beloved, it – and his love – is rejected and is thrown into the road to be crushed beneath the wheels of a cart. Still, the message of the nightingale’s sacrifice echoes on: ‘Love is a wonderful thing. It is more precious than emeralds, and dearer than fine opals.’

Wilde’s second collection of fairy tales, A House of Pomegranates, is more developed and more certain in what it tries to do. Here, the stories are a cohesive quartet; they are richer, darker, deeper. In ‘The Young King’, the hero dreams that the fine cloth of his coronation robe is spun by wretched slaves, and that the beautiful jewels which adorn it are mined by ‘swarms’ of dying men, watched over by Death and Avarice. In ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’, a devoted dwarf dances for the young princess of Spain, and ultimately suffers a broken heart from her indifference and cruelty. ‘The Fisherman and His Soul’ sees a man condemn his soul in order to be with his mermaid lover beneath the sea, while the final story, ‘The Star Child’, concerns a beautiful child who falls from heaven.

Wilde’s second collection of fairy tales, A House of Pomegranates, is more developed and more certain in what it tries to do. Here, the stories are a cohesive quartet; they are richer, darker, deeper. In ‘The Young King’, the hero dreams that the fine cloth of his coronation robe is spun by wretched slaves, and that the beautiful jewels which adorn it are mined by ‘swarms’ of dying men, watched over by Death and Avarice. In ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’, a devoted dwarf dances for the young princess of Spain, and ultimately suffers a broken heart from her indifference and cruelty. ‘The Fisherman and His Soul’ sees a man condemn his soul in order to be with his mermaid lover beneath the sea, while the final story, ‘The Star Child’, concerns a beautiful child who falls from heaven.

Despite their continued presence in the minds and hearts of readers, these stories have often been maligned. A lingering bias about genre and a tendency to take the innocence and simplicity of the stories at face value have prevented the fairy tales from inclusion in Wilde’s legacy, all too easily usurped by the tidy aphorisms of the plays and the juicy Gothic sexiness of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

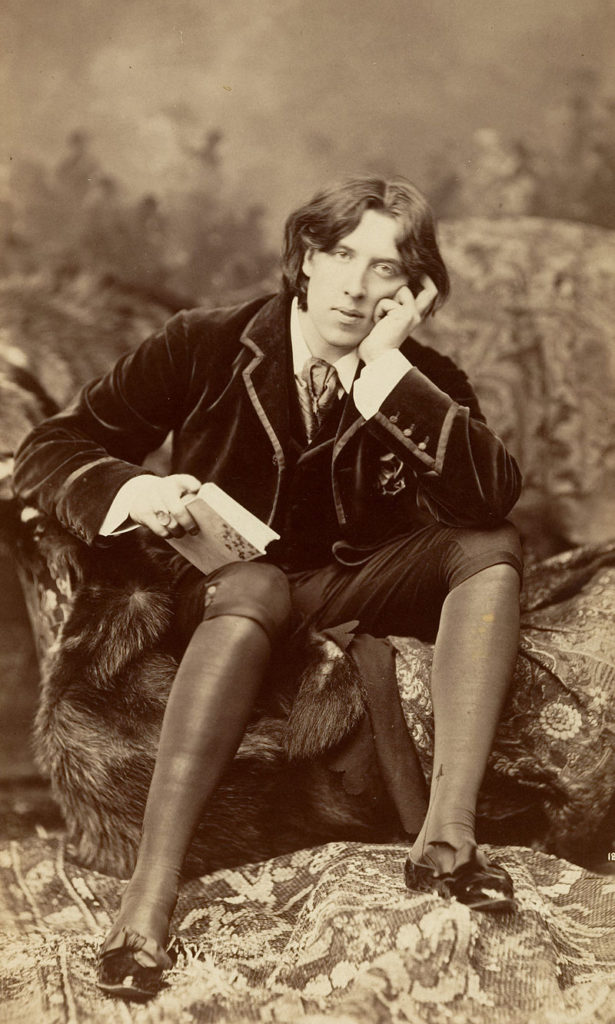

Even the term ‘fairy tale’ is problematic. Fairy tales have often been relegated to the realm of folksy nonsense, non-literary trifles, or worse – children’s literature, and it is still widely believed that Wilde wrote these stories for his own children. In fact, Wilde himself stated that he did not write to “[please] the British child” or even “the British public”, but instead to satisfy himself. Too often, Wilde’s fairy tales have been dismissed as frivolous or sentimental: accused of being too ebullient, too mawkish, too sincere (or not sincere enough); hackish attempts at Victorian didactic morality. Consequently, the golden threads of meaning that make these stories so worth reading have long been neglected within serious literary discourse.

Many people fall in love with these tales simply because they are beautiful. The images in both collections are consistent in their evocations, and will be familiar to those who appreciate the decadent turn-of-the-century aestheticism with which Wilde was so associated: vague mythopoetic European and middle Eastern kingdoms, beautiful palaces and quaint herb-scented peasant houses; gardens of lilies and roses; gold, velvet, myrrh; jewels; ermine; thorns; and of course nightingales – at least one.

Wilde seems to delight in beautiful images for their own sake, and this delight is almost philosophical. When we strip an image of implications and metaphor we can enjoy it on a deeper, more joyful level. “As he is no longer beautiful he is no longer useful”, says the Art Professor in ‘The Happy Prince’, after the prince has been stripped of his gold. Yet, it’s possible to see validity in criticisms of Wilde. His prose has a tendency to take on a purple tinge, and certain motifs can become heavy handed when they are repeated. And perhaps there are too many exoticisms in his writing, too many overly-long descriptions of turquoise, emeralds and rubies; too many descriptions like this one from ‘The Young King’:

He flung himself backward with a deep sigh of relief on the soft cushions of his embroidered couch, lying there, wild-eyed and open-mouthed, like a brown woodland Faun, or some young animal of the forest newly ensnared by the hunters.

Wilde, however, seems to consider beauty on a deeper level, and questions the way in which we attach worth to outward appearances. His characters start out possessing great physical beauty or great wealth, but only achieve enlightenment when they become lowly and ugly. Similarly, in true fairy tale fashion, powerful beings cloak themselves with ugliness to test the virtue of those who would equate beauty of face with beauty of soul. In ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’ the disfigured dwarf is joyful until he looks into the mirror for the first time, destroying his prelapsarian innocence. The story of ‘The Star Child’ shows the heavenly child to be vain and cruel, only becoming good when he is cursed with the ‘face of a toad’ and the scaled body of an ‘adder’.

Wi lde revels in sumptuous descriptions of beauty – exotic jewels, tapestry-draped palaces, beautiful boys and women with feet like white doves – yet he tempers them with rot and ruin’s moral caution, revealing intentions which are more complex than those of the decadent, amoral aesthete worshipping at the altar of hedonistic moral relativism. These tales, like much of Wilde’s ouevre, are strewn with earnest, melancholic allusions to goodness and spiritual truth. Despite the wry quips and witty aphorisms, there is, at their heart, a deep, almost uncomfortable, moral sincerity in these stories.

lde revels in sumptuous descriptions of beauty – exotic jewels, tapestry-draped palaces, beautiful boys and women with feet like white doves – yet he tempers them with rot and ruin’s moral caution, revealing intentions which are more complex than those of the decadent, amoral aesthete worshipping at the altar of hedonistic moral relativism. These tales, like much of Wilde’s ouevre, are strewn with earnest, melancholic allusions to goodness and spiritual truth. Despite the wry quips and witty aphorisms, there is, at their heart, a deep, almost uncomfortable, moral sincerity in these stories.

Christ, crowned in thorns, takes many forms in both collections, whether as an overt expression of Christian morality or simply a visual metaphor for purity, selflessness, and unconditional love. In ‘The Young King’, the spoiled monarch casts off his fineries to reveal a sad and sweet divinity: ‘And the Young King plucked a spray of briar that was climbing over the balcony…and made a circlet of it… “This shall be my crown,” he answered.’ Likewise, in ‘The Selfish Giant’, the religious message is clear. When, after a long absence, the Giant finds the young boy whom he loves standing in his garden bearing the marks of nails in his hands and feet, the child says to him: “these are the wounds of Love…to-day you shall come with me to my garden, which is Paradise.” And in ‘The Happy Prince’, when God directs his angel to bring him the most precious things in the city, the angel collects the leaden heart of the Happy Prince and the body of the dead sparrow.

But this deeply sincere morality is shot through these stories in other, less tangible ways as well. Fairy tales often present the natural order of things as being hierarchical, and associate royalty or aristocracy with goodness, rightness, and spiritual refinement. In these stories, however, Wilde is fiercely critical of the haves and fiercely protective of the have nots. Although the stories delight in the trappings of nobility, the ugliness of riches is palpable. Many a paragraph amongst these magical, seemingly airy-fairy pages would not be amiss in a contemporary socialist polemic. Scintillating, angry jibes at the oppressor class abound, such as:

“In war,” answered the weaver, “the strong make slaves of the weak, and in peace the rich make slaves of the poor. We must work to live, and they give us such mean wages that we die. We toil for them all day long, and they heap up gold in their coffers, and our children fade away long before their time, and the faces of those we love become hard and evil. We tread out grapes, and another drinks the wine. We sow the corn, and our own board is empty. We have chains, though no eye beholds them; and are slaves, though men call us free.”

Wilde presents an abyssal experience of suffering: poverty, misery, and injustice. Yet he also illustrates the redemptive power of love. Of course, these things are readable within the actual texts. The human response is something different, and that response is this: in these fairy tales-cum-short stories is a magic that is sweet, gorgeous, tender, and wholly optimistic in the way that only humanist tragedy can be optimistic. Read them when the world is raw and deeply un-tender, with a watery smile, and feel your heart burst into blossom. Because yes, perhaps Wilde is too much, and perhaps his message is sentimental. These stories are not subtle, arch or fashionably cynical. They are, though, heartbreakingly beautiful, true and essential. And, unequivocally, they are not about nightingales.

~

Louise Murray recently graduated from Queen’s University Belfast with a degree in English. She has previously been published in The Ogham Stone and The Erotic Review, and has been featured on Queen’s Radio. She would be working on a collection of short stories about allegory, dreams, and one very strange hotel, if only she would stop procrastinating.