('Octopus'© Scott Ableman, 2009)

We are delighted to announce the results of the 2018 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition…

~

OUR 2018 WINNER:

Kate Finegan with ‘Meditations On Motherhood’

~

Runners-up:

Erinna Mettler with ‘The Playboy and the Bog Man’

Farah Ahamed with ‘The Tyranny Of History’

Look out for the features from our runners-up on Thresholds next week.

~

Comments from the judging panel on Kate Finegan’s winning entry:

‘The author draws us in with a uniquely involving introduction before delving into “Genus and Species” in an exploration that is itself rich, poignant and precise. It was a real pleasure to discover here, for the first time, the work of Leslie Beckmann […]This is a generous piece of writing in its own right.’

‘The opening section of this piece is wonderful.’

‘It’s rare that an essay moves me, but this one succeeded in achieving that, not only for its passion, but also for the care and respect it shows for both literature and natural history. A tender, intelligent essay, written with real fluency.’

‘This is a beautifully written piece that impressed me in various ways: the lyrical exposition of an octopus’ motherhood, the connection of that striking opening with Beckmann’s story, the close reading and analysis of style of Beckmann’s experimental story…’

‘Elegant, unusual, moving and interesting.’

~

Kate Finegan’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in Phoebe, The Puritan, Midwestern Gothic, The Fiddlehead, and others. Her work won Phoebe‘s creative nonfiction and The Fiddlehead‘s short fiction contests, was runner-up for The Puritan‘s Thomas Morton Memorial Prize, and was shortlisted for the Cambridge Short Story Prize. Her novel-in-progress was a semi-finalist for the James Jones First Novel Fellowship. She lives in Toronto.

Kate Finegan’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in Phoebe, The Puritan, Midwestern Gothic, The Fiddlehead, and others. Her work won Phoebe‘s creative nonfiction and The Fiddlehead‘s short fiction contests, was runner-up for The Puritan‘s Thomas Morton Memorial Prize, and was shortlisted for the Cambridge Short Story Prize. Her novel-in-progress was a semi-finalist for the James Jones First Novel Fellowship. She lives in Toronto.

~

MEDITATIONS ON MOTHERHOOD: LESLIE BECKMANN’S ‘GENUS AND SPECIES’

By KATE FINEGAN

You wouldn’t expect an octopus to break your heart, but that’s because you don’t know octopus mothers. An octopus mother carries her offspring within her body for four or five months before she deposits them, dozens of egg sacs holding thousands of lives, into a safe spot in an unsafe ocean. That, really, is the start of her work—and the end of her life. Imagine blowing dandelion seeds into the air, gathering the seeds, lacing them together, and weaving a delicate curtain. That’s what octopus mothers do—gather their eggs and tie them into pearlescent bunches. Each egg is a teardrop, translucent. The octopus mother attaches her precious strands to a rock. The result looks like a solid waterfall, suspended, enticing to predators. She never leaves her eggs, not once, not even to eat. One octopus off the California coast incubated her eggs for four-and-a-half years, from April 2007 to September 2011. Think of what you did in the span of those four-and-a-half years. Think of all the small (and large) heartbreaks you endured—and all the joys. And think how, for all that time, one octopus didn’t let her hundred-and-sixty egg sacs out of her sight; how she spent all day every day worrying over them, watching for predators, blowing water across them to keep them free of algae, to give them air. A research team returned to her eighteen times over those fifty-three months. Every time, she was in the same spot, shielding the eggs with her body. The team offered her food, which she rejected. They saw her push aside shrimp and crabs, exactly what an octopus likes to eat. The octopus mother will break your heart because she starves herself, and after her eggs hatch, she dies.

In Leslie Beckmann’s ‘Genus and Species’, we learn that octopuses have three hearts, with two chambers each. A human mother, Ellen, thinks about these hearts, wondering:

Were there, in any of those chambers, dreams of shrimp and happiness for her hatchlings? Did they hold hope for hours of building nests and playing with shells in the sea? Did it hurt in any of those three hearts when she thought about how many of her sprogs would be startled by boats, mangled in traps, eaten by fish and birds and seals and whales? Were they breaking as she waited, those six chambers? Or was she just relieved that on their hatching she would die and the fear of helplessness would end with her?

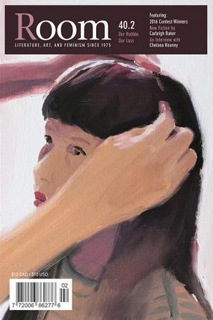

Beckmann’s story, which won the Canadian magazine, Room’s 2016 fiction competition and is published in issue 40.2, begins ‘It had started silently, like a heart attack, when Norah was a dumpling baby, round and not yet walking. The worry.’ By the end of the first paragraph, we learn that Norah is lying in a hospital bed, ‘her skin everywhere hard and puffy, evidence of the afternoon’s battle with a nest of yellowjackets.’

Close third-person narration takes the reader into the mind of Norah’s mother, Ellen, a biologist who ‘retreat[s] to biology in times of fear.’ The author herself is a biologist. Judge Doretta Lau writes that ‘Beckmann’s precise language […] has a scientific beauty to it, imposing a sense of order within a chaotic world.’ From the frame of the sterile hospital room, we are transported into that chaotic world. Ellen’s thoughts carry us from the Vancouver ravine where Norah stepped into a rotten log containing a yellowjacket nest, to Australia, where, long before Norah’s birth, Ellen observed how:

[kangaroo] mothers were alert to the slightest rustle, playing the ancient mothers’ game: letting the joeys spool out like bait on a fishing line until at last an invisible boundary was reached and an alarm went off in their maternal brains.

She takes us to a dark road on the way home from a movie, where ‘four raccoons—one big and three little’ were making their way across when ‘an asshole in a BMW, out of nowhere and heading straight to hell, sped up at them. Clipped the last one in line. Killed it.’ We are there on the road with Ellen, watching ‘the siblings sniffing death, the mother patting the body, pacing away, circling back to pat it once more. Murmuring. Whimpering. Keening with grief.’

This expansive story reads like field notes on love, worry, and grief. The prose is filled with scientific names and precise numbers. We learn that, in the aftermath of the yellowjacket swarm, ‘Ellen had counted each round white welt’—all forty-seven of them. Beckmann uses lists to poetic effect, and these lists echo Ellen’s attempts to bring order to this fraught, fearful moment. Norah is introduced by her measurements, like a specimen: ‘all six years, forty-two inches, and forty-two pounds of her.’ Lists figure prominently in the prose, so that the story calls to mind the notes of botanists, or early biologists, cataloging the life forms they encountered on their expeditions. Ellen has observed ‘crows and ravens and jays and magpies’, ‘in rookeries and trees and city parks: they hunted and honked and ruffled and clucked, anxious parents all of them.’

This expansive story reads like field notes on love, worry, and grief. The prose is filled with scientific names and precise numbers. We learn that, in the aftermath of the yellowjacket swarm, ‘Ellen had counted each round white welt’—all forty-seven of them. Beckmann uses lists to poetic effect, and these lists echo Ellen’s attempts to bring order to this fraught, fearful moment. Norah is introduced by her measurements, like a specimen: ‘all six years, forty-two inches, and forty-two pounds of her.’ Lists figure prominently in the prose, so that the story calls to mind the notes of botanists, or early biologists, cataloging the life forms they encountered on their expeditions. Ellen has observed ‘crows and ravens and jays and magpies’, ‘in rookeries and trees and city parks: they hunted and honked and ruffled and clucked, anxious parents all of them.’

Recently, in an interview at the Toronto Reference Library, author Marilynne Robinson suggested we maintain our sense of wonder by reading current science. She subscribes to Scientific American and claims that reading it is like reading the Psalms. Beckmann’s story, so rich in scientific detail, is undeniably poetic. Beckmann uses repetition throughout, so that the story almost reads like a pantoum or sestina. Her lists form a refrain of and…and…and, reflecting the way worries stack up in our minds, and especially in the minds of mothers. The first two paragraphs both begin with the same three words: ‘It had started.’ Alliteration is used, too, as in the sentence ‘The ravine was August-dry and dusty with leaf rot.’

The narrator explains that ‘Before Norah could walk, the fear was small and nameless and Ellen could fool herself into believing she was the boss of it.’ The use of scientific names throughout the story gives the lie to this statement. We see a world that is ordered beyond the understanding of a biologist, a natural world that is just as vulnerable as a human life. Ellen is bewildered by the loss she finds in the natural world, even though she can name and explain the behaviours of the animals she encounters. What we find is a universal chaos, but also a universal hope. This is not a story without humour. Ellen thinks of the yellowjackets as ‘stinging little shits’ even as she finds that she can’t blame them entirely—after all, what were they doing but protecting their ‘wriggly white larvae that lay suddenly exposed beneath Norah’s sneakered feet’? As Ellen watches her daughter in the hospital bed, she thinks of her daughter’s white blood cells as ‘little mobsters, putting the venom molecules in little cement overshoes.’ Somehow, a story that circles around pain and worry, fear and death, manages to be playful, even funny at times.

The hopeful glimmer in the story shows up early, on the second page, and in direct contrast to the horror of what has happened to Norah: ‘Norah’s foot slid down and off the side of the path and into a yellowjacket nest built in a hollow log, life reusing old spaces as it always did.’ There is lightness in this story, an unfailing faith in the tenacity of life, despite the hardships the world throws at us, humans and animals alike. Even as Ellen realises her fear for Norah will never dissipate, she also realises that ‘Norah would survive. Almost every single child did. It was how Homo sapiens had made it to seven billion on the planet.’ What follows this revelation of hope is a meditation on the pain of motherhood. Ellen characterises her role in Norah’s life as that of:

The hopeful glimmer in the story shows up early, on the second page, and in direct contrast to the horror of what has happened to Norah: ‘Norah’s foot slid down and off the side of the path and into a yellowjacket nest built in a hollow log, life reusing old spaces as it always did.’ There is lightness in this story, an unfailing faith in the tenacity of life, despite the hardships the world throws at us, humans and animals alike. Even as Ellen realises her fear for Norah will never dissipate, she also realises that ‘Norah would survive. Almost every single child did. It was how Homo sapiens had made it to seven billion on the planet.’ What follows this revelation of hope is a meditation on the pain of motherhood. Ellen characterises her role in Norah’s life as that of:

wallpaper, always there, always reliable, ready with arms when they were needed. But that was it. She was an actor in a supporting role now. She would need to be like a volunteer at a bird sanctuary releasing wounded terns, their wings reknit after injury, into the sky.

Ellen imagines the woman Norah will become and takes pleasure in the joys that she will surely experience, while recognizing that the inevitability of joy does not negate the inevitability of pain and sorrow.

This nine-page story manages to pack in a lifetime of pain and just as much joy, across time and across species, as a mother watches her daughter sleep in a hospital bed. We only hear from Norah twice, when she wakes momentarily from her stupor, and the interactions with her mother are authentic and touching. This story is about mothers and daughters, but it is also about life in all its wonderful, tragic forms. After Ellen remembers the octopus ‘puffing fresh water softly through the eggs, breathing them to life’, Norah’s ‘suckling sound of nursing’ brings her back into the hospital room. The story ends with equal parts pain and joy, echoing earlier scenes and images:

Ellen watched her sweet, sweaty child in the hum of the hospital room. So much hurting, and so much joy. And Ellen was the wallpaper, the hands to lob Norah gently back into the sky. That was all she could do Little white spotted forehead. Life. This tiny bird, fledging. Hatching meant breaking eggs.