photo © Mary-Ellen Macciola 2008

by Eleanor Fitzsimons

It sometimes takes an outsider’s gaze to capture the essence of a place with an authenticity that lies beyond the sight of the indigenous observer. For this reason, it should have come as no great surprise to readers of The New Yorker when the Long-Winded Lady, columnist and faithful, if eccentric, documenter of life in the eponymous city, was unmasked as Irishwoman Maeve Brennan, an immigrant who had arrived in her mid-twenties. John Updike, among others, realised that this watchful interloper ‘brought New York back to The New Yorker’. In her whimsical contributions to the exalted ‘Talk of the Town’ column, Brennan was rare in establishing a distinct persona, and unique in ensuring that this voice was a female one. Stylish, ambitious and armed with a waspish wit that conjured up recollections of Dorothy Parker, her personality contrasted violently with that of her passive, suburbanite alter-ego.

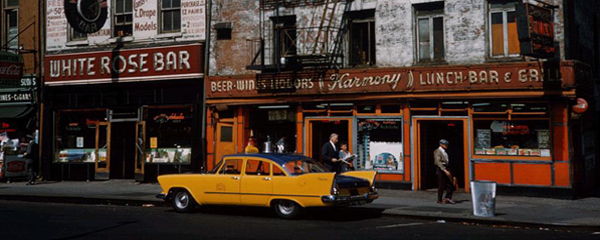

Between 1954 and 1968, Brennan documented a city in flux, a place where the wrecker’s ball swung in perpetual motion as residents embraced a post-war transience. She too drifted: a self-confessed ‘traveller in residence’, she hopped from short-lease apartment to anonymous hotel suite, or borrowed summer houses from glamorous friends like Gerald and Sara Murphy, Fitzgerald’s models for the Divers in Tender is the Night. In her wake she left little beyond a miasma of cigarette smoke and a trace of expensive scent. As one-time editor at The New Yorker Gardner Botsford observed, Brennan could, ‘like the Big Blonde in the Dorothy Parker story … transport her entire household, all her possessions and her cats – in a taxi’. In her story ‘The Last Days of New York City’, published in The New Yorker in 1955, Brennan confessed: ‘All my life, I suppose, I’ll be running out of buildings just ahead of the wreckers’.

Although rarely absent from New York State, Brennan used fiction to return to her native Ireland, which she had left while still in her teens. In The Visitor, her posthumously published novella, she explains why: ‘Home is a place in the mind,’ she writes, ‘when it is empty it frets’. Yet, her memories were never those of a misty-eyed romantic. Born within a year of the failed Easter Rising of 1916, to a staunch Republican father who was in prison at the time but was later appointed Secretary of the Irish Legation to Washington, Brennan was tangled up in political turmoil for much of her early life. The precariousness of her existence and the ever-present threat of displacement seep into stories shot through with anxiety and unease. In ‘The Day We Got Our Own Back’, from The New Yorker in 1953, Brennan documents how she watched wide-eyed as her family home was raided:

One afternoon some unfriendly men dressed in civilian clothes and carrying revolvers came to our house, searching for my father, or for information about him.

Throughout her life, she had a horror of being pinned down and she rarely made firm arrangements.

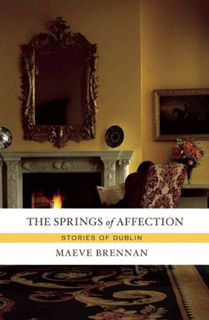

Conventional boundaries between memoir and fiction are rarely observed in Brennan’s revealing Irish stories, many of them collected posthumously in The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin, a book compared favourably to Joyce’s Dubliners. Although these tales of lower-middleclass Dublin life appear superficially innocuous, they revealed an unfamiliar malevolence to second- and third-generation Irish-Americans who hankered after a mist-shrouded holy land. Her characters operate furtively, seeing out their thwarted lives in the shadow cast by a stultifying and spiritless Catholic Church.

Conventional boundaries between memoir and fiction are rarely observed in Brennan’s revealing Irish stories, many of them collected posthumously in The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin, a book compared favourably to Joyce’s Dubliners. Although these tales of lower-middleclass Dublin life appear superficially innocuous, they revealed an unfamiliar malevolence to second- and third-generation Irish-Americans who hankered after a mist-shrouded holy land. Her characters operate furtively, seeing out their thwarted lives in the shadow cast by a stultifying and spiritless Catholic Church.

From the safety of cosmopolitan New York, Brennan time travelled back to darkened confessionals where guilt-ridden children cowered under the gaze of a vengeful deity, and to the ante-chamber of an enclosed convent where a bereft mother strained to discern the voice of a lost daughter who sang in praise of her unearthly spouse. Teaching nuns, capricious in their accusations, note that the young Brennan was headstrong and wilful, traits that are inappropriate in Irish womanhood. Decades later, in ‘Lessons and Lessons and More Lessons’ from The New Yorker, Brennan described how, in a city where the ‘three-martini lunch’ is commonplace, she hid her glass instinctively when two nuns entered the Greenwich Village restaurant she frequented.

In New York, Brennan embraced her ‘otherness’; as one colleague observed, ‘She wasn’t one of us. She was one of her!’ To strangers, she could appear hard-edged and watchful, yet friends found her warm and generous, voluble and funny. Everyone agreed that she was beautiful. Barely five feet tall and beanpole slim, she looked younger than her years and compensated with vertiginous heels. She tottered along the robustly masculine corridors of The New Yorker offices at West Forty-Third Street, make-up immaculate, hair neatly coiffed and carefully chosen costume exquisitely cut, with a fresh flower in her lapel, generally a rose. She had the ceiling of her office painted Wedgwood blue and threw open her door while she tap-tapped away on her typewriter, a curlicue of smoke rising from the ever-present Camel clenched between her fingers. Her language was defiantly fruity, and the mischievous notes that she slipped under the doors of her male colleagues elicited great explosions of laughter: ‘To be around her was to see style being invented,’ recalled her friend and editor William Maxwell.

An ill-fated stint as fourth wife to fellow New Yorker writer St. Clair McKelway – a hard-drinking, mentally frail man – took her to bohemian Sneden’s Landing, a community of artists and writers that nestled alongside the Hudson in upstate New York. Brennan recast it as ‘Herbert’s Retreat’, a rarefied enclave where privileged New Yorkers partied under the watchful gaze of their derisive Irish servants. With an insider’s familiarity, Brennan used her stories to juxtapose the prudent Catholicism of her countrywomen with the flagrant immorality of their employers. As the beautiful and sophisticated daughter of a diplomat, Brennan enjoyed a status that allowed her to pass in society, yet she had rubbed shoulders with girls who would enter domestic service and must have felt a sneaking solidarity with them. As a former fashion writer with Harper’s Bazaar, it apparently amused her greatly when the trappings of Irish peasantry – shawls and tweed and tealeaves – were adopted as status symbols by wealthy American women.

At times, Brennan grasped onto the trappings of Irishness with a fervour that suggested desperation and displacement. She drank tea obsessively, and although her rented homes rarely featured a kitchen, she insisted on an open fireplace, considering a fire to be a living thing, company almost. When her marriage failed in 1959, she embraced a solitary life, borrowing houses in the Hamptons and walking the Atlantic beach with her dog, Bluebell before returning to the twin comforts of a scalding hot cup of tea and a roaring fire, which she shared with several cats, ‘small heaps of warm dreaming fur all over the furniture and the floor’. In summertime, when the Hamptons filled up, she would return to New York City or travel home to Ireland.

During her chaotic, alcohol-soaked marriage, Brennan wrote little of any worth. When one devoted reader requested more Maeve Brennan stories, she had her editor write to explain that she had shot herself when she was ‘drunk and heartsick’. However, the 1960s heralded a period of intense productivity. Several of her finest stories, set in Dublin and Wexford, feature Rose and Hubert Derdon, a couple who endure a dispiriting marriage: she is furtive and priest-ridden, while he ‘wore the expression of a friend, but of a friend who is making no promises’. Carefully crafted, these stories represent a stingingly accurate documenting of the disappointments that ambush even the most virtuous at every turn. Many of the stories from this period were published in In and Out of Never-Never Land. A number of stories from this collection are set in Forty-eight Cherryfield Avenue, in the well-to-do Dublin suburb of Ranelagh, the home she occupied as a child; William Maxwell described it as her ‘imagination’s home’.

Brennan’s story ‘The Eldest Child’ was selected for Best American Short Stories 1968. Yet even as her writing elicited fresh acclaim, her life began to unravel and she drifted, physically and mentally, becoming unkempt, erratic and paranoid. Homeless and debt-ridden, she took to sleeping on a couch in the ladies room at The New Yorker offices, and she grew paranoid that her toothpaste had been laced with cyanide. When she was institutionalised for a time, one friend testified that she became very Irish, as if the years had fallen away, and with them the carefully crafted veneer. She was discharged once she had established a pharmaceutically induced equilibrium, but she could not be relied on to take her medication and drifted once more, losing touch with friends and colleagues. She was nervously tolerated at the offices of The New Yorker as a legacy of affection and with respect for her talent, but her behaviour grew erratic: she once nursed a sick pigeon in her office and, in a more sinister episode, wrecked the offices of a number of colleagues. Sometimes, she stood outside, handing out cash to bewildered passers-by. Inevitably, she produced little that was worthy of publication. Yet ‘The Springs of Affection’, her longest and, arguably, most powerful story, appeared in The New Yorker in March 1972. Although it is almost entirely autobiographical, Brennan twisted the facts in such a fashion that one aunt was prompted to write the words ‘greatly changed for the worse’ on a photograph of her brilliant niece.

Brennan’s story ‘The Eldest Child’ was selected for Best American Short Stories 1968. Yet even as her writing elicited fresh acclaim, her life began to unravel and she drifted, physically and mentally, becoming unkempt, erratic and paranoid. Homeless and debt-ridden, she took to sleeping on a couch in the ladies room at The New Yorker offices, and she grew paranoid that her toothpaste had been laced with cyanide. When she was institutionalised for a time, one friend testified that she became very Irish, as if the years had fallen away, and with them the carefully crafted veneer. She was discharged once she had established a pharmaceutically induced equilibrium, but she could not be relied on to take her medication and drifted once more, losing touch with friends and colleagues. She was nervously tolerated at the offices of The New Yorker as a legacy of affection and with respect for her talent, but her behaviour grew erratic: she once nursed a sick pigeon in her office and, in a more sinister episode, wrecked the offices of a number of colleagues. Sometimes, she stood outside, handing out cash to bewildered passers-by. Inevitably, she produced little that was worthy of publication. Yet ‘The Springs of Affection’, her longest and, arguably, most powerful story, appeared in The New Yorker in March 1972. Although it is almost entirely autobiographical, Brennan twisted the facts in such a fashion that one aunt was prompted to write the words ‘greatly changed for the worse’ on a photograph of her brilliant niece.

Although Brennan continued as an occasional contributor to ‘Talk of the Town’, her offerings arrived out of the blue with no indication of where she was when she wrote them. In her final outing as the Long-Winded Lady, in January 1981, she described how, walking along Forty-Second Street, she had sidestepped a shadow that she recognised as ‘exactly the same shadow that used to fall on the cement part of our garden in Dublin, more than fifty-five years ago’. That year, she turned up at the offices of The New Yorker, grey-haired and unkempt, and sat quietly in reception on two consecutive days, but no one appeared to recognise her. Maeve Brennan died of heart failure in a New York nursing home on 01 November 1993; she was seventy-six. By then, she had descended into an imaginary existence in which she appeared unaware of her status as a celebrated writer.

Excluded from the canon of important Irish writing for years, she has enjoyed a posthumous revival. Two collections of short fiction, The Springs of Affection and The Rose Garden, and her revealing novella, The Visitor, are still in print, as is a collected edition of Long-Winded Lady pieces. Jonathan Cape published Angela Bourke’s biography Maeve Brennan: Homesick at The New Yorker in 2004. Since then, several new plays and collections have referenced the work of this significant Irish writer.

~