('The Essesnce of Egg' © Brenda Gottsabend, 2009)

LOVE AND POISON: ‘ALLERGY’ BY ELSPETH DAVIE

by STEPHEN HARGADON

How do you like yours done? Scrambled, fried, boiled (soft or hard), poached, shirred, sunny side up? In Elspeth Davie’s ‘Allergy’ (from her 1976 collection The High Tide Talker) we meet a man who cannot abide egg in any form. Harry Veitch, who works ‘in the refrigerating business’, is no dilettante when it comes to detesting eggs. They are ‘poison’ to him. There is no argument, no discussion. Veitch appears to be a man of Biblical certainties, unswaying in his belief that in every egg lies catastrophe. It’s a situation at once ominous and absurd, but Davie never strays into whimsy.

The story opens with the Veitch sitting down to breakfast in an Edinburgh lodging house:

The new lodger glanced down briefly at the plate which had just been put in front of him and turned towards the window with a faint smile, as though acknowledging that the day was fair enough outside, even if there was something foul within.

Nimbly deployed near the end of the sentence, that ‘foul’ really hits us, with its suggestion of moral and physical decay. Already there is a tension between two worlds, the inner and the outer, a tension evident in many of Davie’s best short stories. Her technique is subtle, sometimes cerebral, sometimes conversational, and never far from a gleam of lyricism. She has an assured, poetic sense of rhythm and sound – ‘faint’, ‘fair’, ‘foul’ create an echo effect within the sentence – without ever compromising the lightness and immediacy of her prose or its colloquial tone. It is a skill especially apparent in this peculiar, unshowy tale. Davie’s characters very much inhabit a world we recognise – ‘cruelly grimacing human beings’, ‘a street of windows – some of them old and grim’, ‘slabs of wintry stone’, ‘brown pots of creeping plants’ – and they remain in this world, no matter where their thoughts take them.

That confident, mazy opening line is almost a precis of the story itself. Veitch looks outside, supposedly at an uninspiring but tolerable scene, but that ‘foul within’ warns of a more immediate and ominous region. Many of Davie’s stories, flecked with idiosyncratic observation and glinting insight, explore the ‘foul within’ against an everyday backdrop of train stations and guest houses, businessmen and housewives. Here’s the opening exchange:

“I can’t take egg. Sorry.”

“Can’t take?” Mrs Ella MacLean still kept her thumb on the oozy edge of a heap of scrambled yellow.

“No. It’s an allergy.”

“It doesn’t agree?”

“No. It’s an allergy.”

“Oh, one of those. That’s interesting! But you could take a lightly-boiled egg, couldn’t you?”

“No, it’s an allergy to egg.”

“You mean any egg?”

“Any and every egg, Mrs MacLean. In all forms. Egg is poison to me.”

How swift and precise this is, how sharp. Davie’s technique is like that of an illustrator, conveying character in a few deft touches. Here, the internal world is suggested through dialogue. There is a relationship developing between Veitch and Mrs MacLean, and yet Davie makes no reference to how they look or act. There are no smiles, no glances; all we get is Mrs MacLean’s thumb on ‘the oozy edge’ of ‘scrambled yellow’, a painterly touch — Davie herself studied and taught art, and it’s almost as if the landlady is holding an artist’s palette.

How swift and precise this is, how sharp. Davie’s technique is like that of an illustrator, conveying character in a few deft touches. Here, the internal world is suggested through dialogue. There is a relationship developing between Veitch and Mrs MacLean, and yet Davie makes no reference to how they look or act. There are no smiles, no glances; all we get is Mrs MacLean’s thumb on ‘the oozy edge’ of ‘scrambled yellow’, a painterly touch — Davie herself studied and taught art, and it’s almost as if the landlady is holding an artist’s palette.

In Veitch’s liturgical-sounding repetitions (he could be a character from a Pritchett story) we hear conviction, a certain clipped resolve, perhaps even sullen pride, the weary pomp of a travelling businessman. Davie, of course, makes none of this explicit, but it is all there in the abrupt rhythms, the spare dialogue: it’s there in the silence between utterances. Nothing is wasted, nothing is made emphatic. The writing is tight, clean, incisive. The conversation – if it can be called a conversation for it has the cadence of a catechism – is at once menacing and mundane. It is also good fun.

Veitch’s three disavowals recall St Peter denying Jesus. But he does not flinch under questioning, and we suspect he has heard such questions many times before. In this early encounter he is a surly but intriguing presence, laconic, a stranger of ambiguous motive. He is taciturn, certainly, but there is a teasing element to his behaviour, a reluctance to disclose, as if he welcomes misunderstanding. Mrs MacLean dances around him with her questions and suppositions. She is, perhaps, a woman given to fantasy. Their conversation is a kind of courtship, a flinty flirtation around the breakfast table. Yet it’s hard to tell if all this is leading up to a kiss or a row. At last Veitch reveals himself but he does ‘not raise his voice at all’. The landlady withdraws the controversial plate and sits down. She’s been caught. She’s involved. “I’ve known the strawberries and the shellfish cat’s fur. And of course I’ve heard of the egg, though I’ve never met it.” Veitch remains silent. ‘He broke a piece of toast’, a marvellous detail. Mrs Maclean carries on in her excitement: “No, I’ve never met it. Though I’ve met eggs disagreeing. I mean really disagreeing!” Veitch, ‘pressing his lips with a napkin’ (another fine touch), makes things explicit: “Not the same thing … When I say poison I mean poison. Pains. Vomiting. And I wouldn’t like to say what else. Violent! Not many people understand just how violent!”

They have reached a kind of climax. ‘There was a silence while Mrs MacLean with a soft white napkin gently brushed away the scratchy toast-crumbs which lay between them in the centre of the table.’ This opening exchange is a wonderful exercise in concision and subtext, in bringing out inner lives through ordinary speech and seemingly humdrum detail. It’s subtle and convincing; it’s lively. After a swift one and a half pages, most of it dialogue, Davie has set up a love affair of sorts. And like Mrs MacLean we are drawn in.

Things progress quickly:

In the weeks that followed Veitch’s status changed from lodger to paying guest, from paying guest, by a more subtle transformation shown only in Mrs MacLean’s softer expression and tone of voice, to a guest who, in the long run, paid.

Veitch’s cult-like allergy is the focus of their relationship and,

…as often as not the conversation veered round to eggs. As a subject the egg had everything … brilliantly self-contained and clean, light but meaty, delicate yet full of complex far-reaching associations – psychological, sexual, physiological, philosophical. There was almost nothing on earth that did not start off with an egg in some shape or form.

Witty lines, in which Davie gently mocks a symbolic reading of the story, but she does so without compromising the overall tone. We still believe in this lodger and landlady.

Veitch tells Mrs MacLean about loved ones who have tried to poison him with eggs. In Davie, levity is never far from darkness. “Oh no!” cried Mrs MacLean. “Love! Love in one hand and poison in the other!” Soon, Mrs MacLean gives up eating eggs.

She wouldn’t actually say they disagreed with her nowadays. That would be going too far. But how could what was poison to him be nourishment to her?

The couple go out for egg-free meals, she develops egg-free recipes. ‘It seemed as though he had let her take over the entire poisonous side of his life.’ She takes him on tours of historic Edinburgh, but Veitch shows signs of irritation and his work begins to occupy more of his time. Mrs MacLean imagines him with ‘some mature and still seductive woman’. She is forced to take days out on her own.

She visits country pubs where they used to enjoy egg-free meals together. Once the grim world travelled past the windows of her boarding house, now she glides silently past hills and lanes, unable to forget about Veitch and his mysterious allergy. During one such trip, on ‘one of the last warm days of the year’, away from the busy streets with their ‘unsympathetic’ faces, she leans on a gate and takes in the ‘line of the Crags and Arthur’s Seat with the blue haze of the city beneath’. Closer in, she notices that ‘the weeds of the fields and ditches were a bright yellow, yet creamed here and there in the hollows with low swathes of ground-mist’. She is not alone: there’s her lodger, the egg-avoider, ‘Seated on a tartan rug which came from the back of her own drawing room sofa’ with his ‘arm around the waist of a young woman whose hair was as yellow as egg yolk’. There is no melodrama, no confrontation, just the silent pain of defeat. As ever, Davie finds the telling detail: ‘Mrs MacLean noted that under a dusting of seeds and straws Veitch’s shoes still bore traces of the very shine she had put there the night before.’ Our Mrs MacLean, our ‘amiable woman in her middle years’, retreats unseen to the city.

She visits country pubs where they used to enjoy egg-free meals together. Once the grim world travelled past the windows of her boarding house, now she glides silently past hills and lanes, unable to forget about Veitch and his mysterious allergy. During one such trip, on ‘one of the last warm days of the year’, away from the busy streets with their ‘unsympathetic’ faces, she leans on a gate and takes in the ‘line of the Crags and Arthur’s Seat with the blue haze of the city beneath’. Closer in, she notices that ‘the weeds of the fields and ditches were a bright yellow, yet creamed here and there in the hollows with low swathes of ground-mist’. She is not alone: there’s her lodger, the egg-avoider, ‘Seated on a tartan rug which came from the back of her own drawing room sofa’ with his ‘arm around the waist of a young woman whose hair was as yellow as egg yolk’. There is no melodrama, no confrontation, just the silent pain of defeat. As ever, Davie finds the telling detail: ‘Mrs MacLean noted that under a dusting of seeds and straws Veitch’s shoes still bore traces of the very shine she had put there the night before.’ Our Mrs MacLean, our ‘amiable woman in her middle years’, retreats unseen to the city.

It is time for one last breakfast. Mrs MacLean, newly vigorous, serves it to Veitch who shows ‘a strange hesitation in lowering himself into his seat’. She holds a teapot, its ‘spout cocked at his ear as though she would pour the brown brew into his skull.’ Veitch shrinks from her.

A simple plot, an unremarkable infatuation. Lonely woman. Intriguing stranger. A betrayal. The elements are familiar. But there is a richness here, a resonance, an ability, keen and tender, to look at the world from odd angles, to see the extraordinary, the mystical, in the daily churn of human commerce. She is the best kind of writer, one whose insights are fresh, surprising, and thrilling to read. She is also funny: ‘on his forehead was a faint glow which was nothing more nor less than the beginning and end of a Scottish sunburn’.

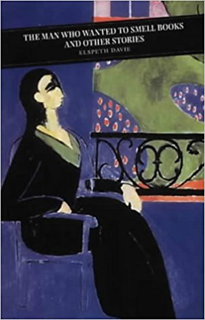

Born in Ayrshire in 1918, Davie spent most of her working life in Edinburgh. That great city, with its grand castle and impoverished suburbs, forms the backdrop to much of her fiction. She published four novels and five short story collections. Shamefully, most of her books are out of print, although Canongate produced an anthology in 2001, The Man Who Wanted to Smell Books. In 1978 she won the Katherine Mansfield Prize for Short Stories but overall her fame was slender and in death it remains so. A shy woman, she seems to have been overshadowed by lesser, noisier writers. On her death, in 1995, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson wrote in the Independent:

She did not seem to mind this state of neglect, indeed she was touchingly grateful for any praise or recognition … Like many other writers, with a strange, elusive but nevertheless strong voice, she remains to be discovered.

The High Tide Talker is an excellent collection, full of memorable, bizarre, sad, sometimes eerie stories: a preacher at a seaside resort shouting over the noise of waves; a conversation at a bookstall; a man with a compulsion to be photographed; a train-loving professor who becomes a fanatical cyclist. All these stories verge on the supernatural without ever leaving the strangest place of all, the human world of work and love and eating eggs.

One image from ‘Allergy’ stands out. Veitch and his landlady look outside. ‘On the pavement below their window, a well-dressed man stopped in the swirling dust to unwind a strip of paper which had wrapped itself round his ankle like a dirty bandage.’ Davie’s stories are like that strip of paper: they wrap themselves around your thoughts. Her voice is strong and persuasive. ‘Allergy’, despite its wistful eccentricity, gives us a world we know, mundane and grubby, full of anxiety, longing, failure and gossip, yet among the ‘buttery omelettes and feathery soufflés’ we find wit and mystery, a world that seems on the edge of becoming something else. It’s a strange, compelling vision.

~

Stephen Hargadon’s distinctive short stories have appeared in Black Static, Popshot, Structo, The Shadow Booth and LossLit. For Helen Marshall his writing is ‘wise, witty, and wonderfully dark’, while Nicholas Royle describes him as having ‘a good eye and a good ear’. Hargadon was shortlisted for the 2017 Anthony Burgess/Observer prize for arts journalism and was a runner-up in the Irish Post’s 2016 short story competition. ‘Just Browsing’, his essay on the enduring allure of second-hand bookshops, can be found on the Litro website. Hargadon has read from his work at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation. He has an MA in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University and continues to produce short stories. He is working on a novel. Website: stephenhargadon.co.uk

Stephen Hargadon’s distinctive short stories have appeared in Black Static, Popshot, Structo, The Shadow Booth and LossLit. For Helen Marshall his writing is ‘wise, witty, and wonderfully dark’, while Nicholas Royle describes him as having ‘a good eye and a good ear’. Hargadon was shortlisted for the 2017 Anthony Burgess/Observer prize for arts journalism and was a runner-up in the Irish Post’s 2016 short story competition. ‘Just Browsing’, his essay on the enduring allure of second-hand bookshops, can be found on the Litro website. Hargadon has read from his work at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation. He has an MA in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University and continues to produce short stories. He is working on a novel. Website: stephenhargadon.co.uk