(‘Okadas’ © Daniel lam, 2010)

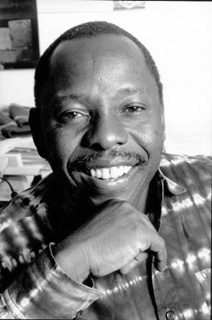

KENULE BEESON SARO-WIWA: WRITER AND ENVIRONMENTALIST

by STANLEY ECHEBIRI

In an interview he granted several months before his execution, Ken Saro-Wiwa was asked what he would like his epitaph to read. He jokingly replied, ‘Here lies the sweet small man Nigeria loves to cheat, they even denied him six feet of the earth at death.’

Sadly, Saro-Wiwa’s words came to pass later. After receiving a death sentence in a kangaroo court, he was hanged alongside eight of his Ogoni kinsmen. Following their execution, the Nigerian state hurriedly disposed of their bodies in a mass grave at the Port Harcourt national cemetery. Witnesses revealed that concentrated acid was poured on the corpses of the nine men to char them beyond recognition.

During his lifetime, Saro-Wiwa was never short of words to express himself and his predicament – whether written or spoken – he was both an orator and a writer. He was undoubtedly Nigeria’s most humorous author and used wit to drive home the message in many of his works. Whether in his TV comedy, Basi and Company, or his popular and daring novel written in ‘rotten English’, Sozaboy. In an interview with Laura Seay of The Washington Post, Roy Doron and Toyin Falola – co-authors of Saro-Wiwa’s biography, The Complex Life and Death of Ken Saro-Wiwa, described him as ‘the Nigerian Mark Twain’.

He created works that used the particular Nigerian vernacular and coupled that mastery of the local variation of English with a biting wit and sarcasm that resonated with his compatriots of all ethnicities. He showed all Nigerians that they had something in common, whether through his serialized novel, Prisoners of Jebs, or his popular television show, Basi & Company.

Across Nigeria and the international community – especially among readers born after the 1980s – not many remember Ken Saro-Wiwa as a literary writer, or an acclaimed one, at that. Much of Saro-Wiwa’s writings in the late 1980s and early ’90s focused on nonfiction, steeped in his struggle for justice for his people, and the environmental activism which led to his murder. He was held in high regard around the world because of his passionate support of these causes. Saro-Wiwa died as a freedom fighter and an environmentalist, yet writing was his most potent weapon against the Nigerian state. His environmental crusade overshadowed his literary achievements towards the later years of his career, but it didn’t remove his footprints on the Nigerian literature landscape. This is evidenced by the literary works he left behind, and innumerable accolades he received (there is even a street in Amsterdam named after him).

Across Nigeria and the international community – especially among readers born after the 1980s – not many remember Ken Saro-Wiwa as a literary writer, or an acclaimed one, at that. Much of Saro-Wiwa’s writings in the late 1980s and early ’90s focused on nonfiction, steeped in his struggle for justice for his people, and the environmental activism which led to his murder. He was held in high regard around the world because of his passionate support of these causes. Saro-Wiwa died as a freedom fighter and an environmentalist, yet writing was his most potent weapon against the Nigerian state. His environmental crusade overshadowed his literary achievements towards the later years of his career, but it didn’t remove his footprints on the Nigerian literature landscape. This is evidenced by the literary works he left behind, and innumerable accolades he received (there is even a street in Amsterdam named after him).

Born Kenule Beeson Saro-Wiwa, he was educated at Government College Umuahia, and at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. He briefly taught at the University of Lagos until the outbreak of Nigeria’s civil war. During the war, he took sides with the Federal Forces, fearing what would happen to his people, a minority, if the government’s opponents – the Igbos – were victorious. After the war, he later rose to the position of Administrator of Bonny (an administrative council in River State), before turning to writing in the early 1970s.

His first major works, Songs in Time of War and Sozaboy, were both published in 1985, but Saro-Wiwa churned out over a score of literary works, including poetry, plays, and short story collections, during his lifetime.

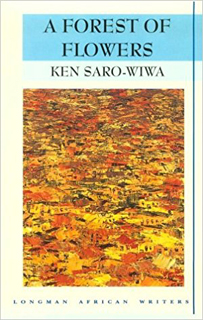

While he was well known for his effective ecological crusades and brushes with the Nigerian military junta, Sani Abacha, those who knew about his writings only knew about his novels and soap opera. Surprisingly versatile, Saro-Wiwa was also a highly accomplished short story writer. He had a harvest of successes, buoyed by the positive reception and acclaim for his first short story collection, A Forest of Flowers, which was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers Prize in 1987. He went on to publish two other short story collections: Adaku and Other Stories and The Singing Anthill.

A Forest of Flowers is widely acknowledged as Saro-Wiwa’s best collection. Literary critic Graham Hough described the stories as ‘brief epiphanies, each crystallising a moment, a way of living, the whole course of a life’. The book is divided into two parts: the first is set in a small rural town surrounded by a forest – Dukana – while the second is set in different cities, Aba, Port Harcourt, Lagos and Kano. The nineteen stories in the book make good reading on any day, but two stories in particular – ‘A Family Affair’ and ‘The Bonfire’ – stand out from the pack, partly because of the solemn nature of their themes, and also because of their resonance with Saro-Wiwa’s fate. Both stories depict social cruelty, injustice and the barbarism a society can unknowingly descend into.

In ‘A Family Affair’, a vibrant young man, Dabo, lives with his family in Dukana. He is seen displaying signs of insanity or madness. Rather than bear the shame of seeing one of theirs running mad, the superstitious family conspires and settles it secretly as a family affair. It is the way it is done in Dukana. The story begins:

When one morning Dabo, one of Dukana’s most successful fishermen instead of heading for the creeks, suddenly bursts out in a song there was consternation in town […] That morning, Dukana was not amused. Ripples of worry gradually spread around town and drew everyone to Dabo’s town.

Even Dabo’s coherency in arguments could not spare his life, rather it mystified his family:

The relatives were surprised at the amazing clarity of the man, was he not mad? How was he able to distinguish between life and death? Could even madness know the difference between the two? Each asked himself the question. Each resolved within himself to bury the answer with the mad beggar.

And so it goes. Dabo is barbarically buried alive by his family. Saro-Wiwa delves into the murky waters of mental illness and the ignorant response of the community.

The story reminds one of Saro-Wiwa’s own barbaric hanging by the Nigerian state, in defiance of the international community, maintaining that the issue was Nigeria’s internal affair: a family affair. Nigeria was suspended from the Commonwealth for this, while many nations sanctioned and also severed diplomatic links with her.

Another barbaric murder with echoes of Saro-Wiwa’s execution is played out in ‘The Bonfire’. Also set in Dukana, it tells of a young man, Nedam, who is burned because his community believe he is a harbinger of evil and the cause of unexplained deaths that have rocked Dukana. Suspicion falls on him because he was born with two teeth in his infant mouth. He stands out too, because he does not conform to his people’s customs. For this, Nedam is burned alive in his house:

Another barbaric murder with echoes of Saro-Wiwa’s execution is played out in ‘The Bonfire’. Also set in Dukana, it tells of a young man, Nedam, who is burned because his community believe he is a harbinger of evil and the cause of unexplained deaths that have rocked Dukana. Suspicion falls on him because he was born with two teeth in his infant mouth. He stands out too, because he does not conform to his people’s customs. For this, Nedam is burned alive in his house:

It was over in a flash. They seized him by the throat, so that he could utter neither word nor cry; and dragged him away towards his house. They threw him in a heap into the house and locked shut the door in his face. They struck the match and set the house ablaze. Soon, a whirlwind of fire raced upwards and rose into the sky like the tongue of a huge torch […] And now came a horrendous clamour of human screams, a shriek of anguish and terror which rose above the bonfire. As the house burned, the youth of Dukana formed themselves into a ring round it to ensure their victim did not escape.

The murder of Nedam reminds me of the final acts before the execution of Saro-Wiwa, and those who died alongside him: how they were led from the condemned criminals’ cell to the execution chamber, the final moments of helplessness, and almost inaudible wail of the nine men who, like Nedam, were innocent. In this final act, you realise that Dukana is presented as a microcosm of Nigeria, steeped in injustice and terror.

The themes of Saro-Wiwa’s short stories are also to be found in his novels and poems: satire, folklore and village life, and the ills of modern day Nigeria. I became deeply entranced by Saro-Wiwa’s works because his themes are easy to connect with, and also because his life itself makes a perfect story. But more importantly to me, I have the privilege of sharing my birthday with this great writer. Although I do not believe in astrology, all the same, I’m tempted to believe that I might become an accomplished writer, with Saro-Wiwa as a guiding star. My play, On the Eve of Commonwealth, a satirical drama on the trial and murder of Kenule Beeson Saro-Wiwa, is a testament to this aspiration.

~

Ikechukwu Echebiri’s work has been longlisted by Alt Publish, Brilliant Flash Fiction, Lifesaver magazine and the CIAP essay contests. His short story was recently published in Alt Publish. He has five published books. His early plays, On the Mind of the Teens and On the Eve of Commonwealth, are used in the educational curriculum in his native Nigeria. Three of his works, Emotionomics- Principles of True Love and Courtship (non-fiction), A Tale of Two States (a novella), and The Trial of Eze Iboko (a historical play), are also published on the Amazon Kindle.