Photo by Nicole Wijnands

By Kath McKay

Flannery O’Connor is funny and wise, and her writing takes my breath away.

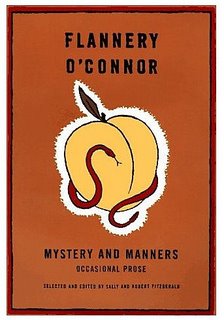

I first read her collection of essays, Mystery and Manners, when I was studying at Goldsmiths in 1986. Why, after all this time, does she still mean so much to me? Why do I keep returning?

O’Connor reminds us how a good short story works. To her, writing is to be taken seriously, yet ‘The material is no more exalted than any other kind of material and the idea of making it right is what should be applied to all making.’

As a ‘country woman’ who read O’Connor’s stories once said, ‘Well them stories just gone and shown you how some folks would do.’

O’Connor pursues this idea, writing:

When you write stories, you have to be content to start exactly there – showing how some specific folks will do, will do in spite of everything.

Now this is a very humble level to have to begin on, and most people who think they want to write stories are not willing to start there.

As a Catholic living in the Bible Belt, her faith informed her writing, but her work never descends into religiosity. She read theology ‘to make my writing bolder,’ and wrote about Protestant preachers and prophets ‘because they express their belief in diverse kinds of dramatic action which is obvious enough for me to catch.’

As a Catholic living in the Bible Belt, her faith informed her writing, but her work never descends into religiosity. She read theology ‘to make my writing bolder,’ and wrote about Protestant preachers and prophets ‘because they express their belief in diverse kinds of dramatic action which is obvious enough for me to catch.’

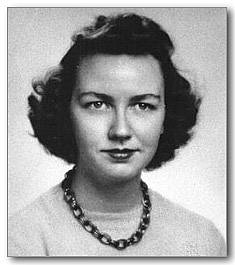

From the age of 25 until her death at 39, she was ill with lupus, and she claimed she wrote ‘out of a terrible need’:

I write only about two hours every day because that’s all the energy I have, but I don’t let anything interfere with those two hours, at the same time and same place.. Something goes on that makes it easier when it does come well. And the fact is, if you don’t sit there every day, the day it would come well, you won’t be sitting there.

In 1986, I was ready to soak up influences. The first time I took the East London line from Whitechapel to New Cross, it felt like the beginning of a new life. I was grappling with creating characters. O’Connor talked of ‘the mystery of personality’, and how to draw on the ‘manners’ of the surrounding society. And what to do with the characters:

The peculiar problem of the short- story writer is how to make the action he describes reveal as much of the mystery of existence as possible… He has to do it by showing, not by saying, and by showing the concrete- so that his problem is really how to make the concrete work double time for him.

These sentiments were new to me, and most fledgling writers.

She wrote as a practising writer facing the blank page every day.

At Goldsmiths, I was taught by Buchi Emecheta, the Nigerian novelist. Each week, she’d ask for twelve pages of writing. Between Buchi and O’Connor, I buckled down.

O’Connor drew on the manners and customs of the ‘Christ-haunted’ South, but resisted parochialism. With her ‘grotesque’ characters, her ugly, mean-spirited children, her deluded preachers and prophets, her bossy, ‘respectable’ older women, she created a world populated with characters I recognised.

She taught me that fiction begins in the senses:

I think one reason that people find it so difficult to write stories is that they forget how much time and patience is required to convince through the senses.

Now this… has to be learned in the habits…to become a way that you habitually look at things.

She added, ‘learning to see is the basis for all the arts except music… Fiction writing is very seldom a matter of saying things; it is a matter of showing things.’

things; it is a matter of showing things.’

O’Connor’s stories are packed with references to sight and vision. Many characters wear spectacles. There are widows and orphans in her fiction, and people with missing or maimed body parts.

She is scathing towards those more interested in ‘being a writer’ than in writing, and contemptuous of ‘pious uplifting’ and false ‘compassion.’

Yet by looking at people with her clear artist’s eye, and being able to make something funny, and sacred, out of violence and ignorance and scabs and body parts, she is like Lucien Freud – making something beautiful out of sagging flesh. She paints human beings in all their frailty. It’s interesting, though not entirely surprising, that she began as a cartoonist (a book of her early cartoons has just been published).

Of the creative process, she said: ‘The more stories I write, the more mysterious I find the process and the less I find myself capable of analysing it.’

But, discussing what makes a good short story, she concludes:

Some action, some gesture of a character that is unlike any other in the story, one which indicates where the real heart of the story lies. …an action or a gesture which was both totally right and totally unexpected; it would have to be one that was both in character and beyond character; it would have to suggest both the world and eternity.

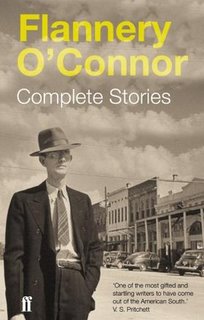

Of course her essays would mean nothing if her stories didn’t stand up. Two favourites are ‘Good Country People’ and ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’, both found in O’Connor’s Complete Stories.

‘Good Country People’ begins with Mrs Hopewell and Mrs Freeman, sitting in a kitchen, mostly talking rubbish. Then Mrs Hopewell’s daughter Joy/Hulga, who lost a leg in childhood, stomps in: ‘the large hulking Joy, whose constant outrage had obliterated every expression from her face.’

My students have complained that nothing happens at the beginning of ‘Good Country People’. Yet O’Connor sets a scene, establishes a tone. The two women chat, while Hulga simmers. The quiet mundanity of the scene lulls us, so we are shocked at events. Hulga, who ‘has a number of degrees’ and ‘believes in nothing’ has arranged to meet a Bible salesman who called:

She had started thinking of it as a great joke and then she had begun to see profound implications in it. She had lain in bed imagining dialogues for them that would be insane on the surface but that had reached below to depths that no salesman would be aware of.

He carries his valise of Bibles on their walk: ‘You can never tell when you’ll need the word of God, Hulga.’

When the salesman kisses Hulga in the hayloft, we are told that ‘She had never been kissed before and she was pleased to discover it was an unexceptional experience and all a matter of the mind’s control. Some people might enjoy drain water if they were told it was vodka.’

Inside his valise are two Bibles, one hollow, with a bottle of whisky, a pack of cards, and a small blue box with printing on it: ‘This product to be used only for the prevention of disease.’

Inside his valise are two Bibles, one hollow, with a bottle of whisky, a pack of cards, and a small blue box with printing on it: ‘This product to be used only for the prevention of disease.’

He asks her to remove her wooden leg and finally runs off with it, shouting ‘I’ve gotten a lot of interesting things. One time I got a woman’s glass eye this way… and I’ll tell you another thing, Hulga… you aint so smart. I been believing in nothing since I was born!’

O’Connor says:

When I started writing that story, I didn’t know there was going to be a PhD with a wooden leg in it. I merely found myself one morning writing a description of two women I knew something about, and before I realised it, I had equipped one of them with a daughter with a wooden leg. I brought in the Bible salesman, but I had no idea what I was going to do with him. I didn’t know he was going to steal that wooden leg until ten or twelve lines before he did, but when I found out that this was what was going to happen, I realised it was inevitable.

‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’ has tension from the start. A grandmother doesn’t want to go to Florida with her family, but instead to Tennessee. She wears white cotton gloves and smart clothing and knows that ‘In case of an accident, anyone seeing her dead on the highway would know at once that she was a lady.’ She has read about an escaped criminal called The Misfit. The family drive through Georgia, passing a large cotton field with five or six graves, and eat at a barbecue place called The Tower. The proprietor has also read about The Misfit: ‘I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if he didn’t attact this place right here.’

The family’s car ends up in a ditch, and The Misfit and his henchmen roll up.

After the grandmother recognises him, he politely instructs his men to lead the males, and then the females, off into the woods. There is the sound of gunfire. The grandmother is alone with the Misfit. His voice cracks, he seems about to cry. She moves towards him: ‘Why, you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children!’ He shoots her.

That ‘action or gesture both totally right and totally unexpected’?

Anne Tyler says ‘every really lasting story contains at least one moment of stillness that serves as a kind of pivot.’

Flannery O’Connor evokes moments of stillness, the mystery at the heart of existence. Read her.

References

Tyler, Anne, ed. with Ravenel, Shannon, The Best American Short Stories 1983, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin 1983), p xiv.

O’Connor, Flannery, Mystery and Manners, (London: Faber 1984).

O’Connor, Flannery The Complete Stories (London: Faber 2009).

Thanks for foregrounding O’Connor’s work. I haven’t read all her stories but ‘Good Country People’ is one I will never forget. Love her acerbic observation and poignant humour.

Thanks for this and for drawing my attention to O’Connor’s essays , which shockingly, I didn’t know about – though as a short storyist she’s been one of my lodestone’s for years. She’s so unflinching and so original. Her writing reminds me of that Emily Dickinson line “Tell the truth/ but tell it slant.”

Thanks very much for an interesting read. I haven’t read Flannery O’Connor but I certainly will do now.

She’s one of my all-time favourite writers, Kath. I’m re-reading her work a little at a time these days. and I love it all over again just reading your piece. You’ve captured so lucidly the remarkable force of her stories. It’s incredible that she achieved such a standard of writing by the time of her death in her late thirties; really moving and humbling. As you say, there’s such a sense of mystery and the sacred arising from stories of grotesque bodies, cheap salesmen and dirt roads. That – and the perfect pitch of her prose – is what grips me too. Many thanks for a wonderful read.