photo by Simeon Eichmann

by Hugh Fulham-McQuillan

You could say Julio Cortázar was destined to write from the moment he was christened with the name Julio, after the French writer Jules Verne. As a child he suffered from asthma and spent much of his time in bed while the echoes of children’s laughter came in through the window from the streets outside. On occasion, when his health allowed, he played with his sister in their back garden. His mother, an admirer of Verne, supplied her son with the novels of his namesake. These allowed the young Cortázar to travel to the centre of the earth, and many leagues below the sea, among other fantastical destinations, without having to leave the confines of his home.

Though sickly, Cortázar was curious about the world, and he was mischievous too. At the age of nine, he surreptitiously borrowed a collection of Edgar Allen Poe’s short stories from his mother. He devoured the tales at night beneath the bedclothes, an environment perfectly suited to the American master of uncanny horror. Reading Poe at such a young age made him ill for three months because, ‘I believed in it . . . for me, the fantastic was perfectly natural’.

A knowledge of where and when he lived (Belgium: 1914, Argentina: 1917, France: 1951-1984), whom he loved (Aurora Bernárdez, Ugne Karvelis, Carol Dunlop), and what he did when he wasn’t writing (high school teacher, professor of French literature, human rights activist, political prisoner, supporter of the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, trumpet player), provides hints of the inner world from which his writing came. In an attempt to brush past these biographical details, as we travel deeper into his inner landscape, an examination of the books he devoured as a child is helpful.

In an interview with the magazine Plural in 1975, Cortázar recounted his childhood. He could well have been describing the atmosphere of his own stories: ‘I spent my childhood in a haze full of goblins and elfs, with a sense of space and time that was different to everybody else’s.’

In an interview with the magazine Plural in 1975, Cortázar recounted his childhood. He could well have been describing the atmosphere of his own stories: ‘I spent my childhood in a haze full of goblins and elfs, with a sense of space and time that was different to everybody else’s.’

The circumstances of his health can only have contributed to this hunger for words. He read many more books than those of Poe and Verne, but when questioned about his childhood, these two authors were often mentioned. It is no surprise to anyone who has read Verne that Cortázar’s early readings of the French author instilled in him a desire to travel. But the stories of Poe resonated somewhere deeper within.

Cortázar’s imagination must have crackled and fizzed with the remnants of hundreds of stories, stories which were barely decipherable from his dreams and distant memories. Yet his writing can be navigated through the works of just two authors: Poe and Cortázar’s Argentinian mentor, Jorge Luis Borges. Both writers serve as the magnetic poles of Cortázar’s inner landscape.

Of Borges, he said:

…his was not a thematic or idiomatic influence but rather a moral one. He taught me and others to be rigorous, implacable in our writing, to publish only what was accomplished literature.

Despite this assertion, many believe that Borges had a great thematic influence on the young Cortázar. Borges’ writing marked a move away from the baroque style that was so pervasive in Latin American literature at the time. Cortázar inherited Borges’ distaste for the baroque. He also inherited Borges’ playful intellectual style, which incorporated intellectual paradox and the fantastical. It is these themes that provide the backbone for many of Cortázar’s early stories and which make them almost inseparable from the writing of Borges.

Borges was also an aficionado of Cortázar’s short stories:

…no one can retell the plot of a Cortázar story, each one consists of determined words in a determined order. If we try to summarize them, we find that something precious has been lost.

He was, however, less enthusiastic about Cortázar’s novelistic attempts: ‘He is trying so hard on every page to be original that it becomes a tiresome battle of wits, no?’

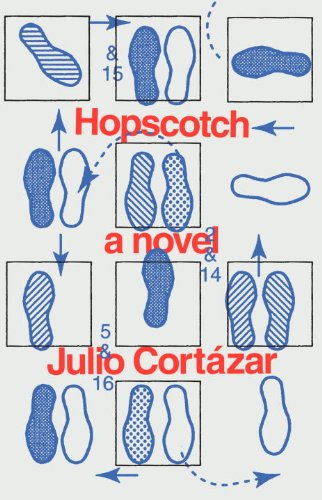

Luis Leal, the Mexican-American author and literary critic, believed Cortázar’s move to Paris was an attempt to escape the influence of the all-encompassing labyrinths of Borges’ fictions. It was only when Cortázar arrived in Paris and began work on his groundbreaking novel Hopscotch that he finally found his own voice, albeit a voice flecked with the accents of his antecedents along with the experimental tones of jazz. It was this novel, with its numbered chapters that could be read in a variety of different orders, which cemented his status as one of the most influential Latin American authors in the latter half of the 20th century.

Luis Leal, the Mexican-American author and literary critic, believed Cortázar’s move to Paris was an attempt to escape the influence of the all-encompassing labyrinths of Borges’ fictions. It was only when Cortázar arrived in Paris and began work on his groundbreaking novel Hopscotch that he finally found his own voice, albeit a voice flecked with the accents of his antecedents along with the experimental tones of jazz. It was this novel, with its numbered chapters that could be read in a variety of different orders, which cemented his status as one of the most influential Latin American authors in the latter half of the 20th century.

By an accident of birth, Cortázar came to fame at the same time as the Latin American Boom writers. In the 60s and 70s, this group of South American writers found international recognition. The most celebrated members of the Boom – Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes and Mario Vargas Llosa – became famous for their use of magical realism; a style that incorporated magical and fantastic happenings into otherwise ordinary situations. It is tempting to include Cortázar among the magical realists, and many have done so, but there are subtle differences that separate Cortázar’s stories.

In the majority of magical realist fiction, the magic is of a benevolent nature; in Cortázar, it is frequently malicious. Strange things happen to his characters. In ‘A Yellow Flower’, a man spots a boy on a bus who appears to be his reincarnation. Horrified at this, he ingratiates himself into the boy’s family and poisons him. In ‘Taken Over’, a brother and sister live in an old house which an unnamed and undescribed thing gradually takes over. In the end they run away, but not before locking up: ‘it wouldn’t do to have some poor devil decide to go in and rob the house, at least not at that hour and with the house taken over.’ Another significant difference is in the setting of his stories. Many Cortázar stories are set in European locations, as opposed to the South American locations favoured by the magical realists, and he frequently features cosmopolitan characters who could be from anywhere, rather than the colourful and decidedly Latin characters found in, say, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s works.

It is when we view Cortázar’s work through the perspective of Poe and Borges that the seemingly magical realist sheen of his stories becomes transparent – instead, the uncanny atmosphere of Poe fuses with the intellectual games of Borges. For an author who was fond of self-reflexivity, Cortázar’s literary lineage is fittingly reflexive: Borges has often acknowledged the influence of Poe on his own writings. So Cortázar is influenced by Poe, and in turn by Poe reimagined by Borges. One way to describe his writing would be to imagine Poe writing his stories as an Argentinian who was born in Belgium in the twentieth century. Or to simplify, Poe with Gauloises and coffee and the faint sounds of jazz coming from somewhere nearby.

In his essay ‘On Feeling Not All There’, Cortázar explains his writing: ‘Much of what I have written falls into the category of eccentricity, because I have never admitted a clear distinction between living and writing.’

In his essay ‘On Feeling Not All There’, Cortázar explains his writing: ‘Much of what I have written falls into the category of eccentricity, because I have never admitted a clear distinction between living and writing.’

Identity is a core preoccupation of Cortázar’s fiction. People lose their identities as easily as trees lose their leaves. Others find themselves fighting to protect their identity from the grasp of other versions of themselves, or they drift into unknown identities that wreak havoc on those around them. In the story ‘Secret Weapons’, a graduate student is invaded by the increasingly persistent memories and character quirks of a dead Nazi soldier who had once raped his girlfriend when she was a child. In the almost flash fiction length ‘Continuity of Parks’, the reader of a novel follows the path of its protagonist who is on his way to murder said reader who remains oblivious and caught up in his book. Meanwhile, we, the actual readers of the story, cringe in anticipation while enjoying the audacity of Cortázar:

The woman’s words reached him over the thudding of blood in his ears: first a blue chamber, then a hall, then a carpeted stairway. At the top, two doors. No one in the first room, no one in the second. The door of the salon, and then, the knife in hand, the light from the green windows, the high back of the armchair covered in green velvet, the head of the man in the chair reading the novel.

Cortázar’s fame has waned since his death, yet many writers and readers continue to cite his work amongst the very best. In an interview, Chilean author Roberto Bolaño (whose fame has, incidentally, waxed since his recent death) counted Cortázar’s Hopscotch among the five books that marked his life for the better. Bolaño has also said Hopscotch was the main inspiration for his novel The Savage Detectives.

On the day of his death, the Spanish newspaper El País hailed Cortázar as one of the greatest writers to emerge from Latin America. Bolaño is just one of the more eminent of Cortázar’s successors; the future will surely reveal more.

To end with a beginning, my introduction to Cortázar came when I had written a short story about the 16th century Italian composer Gesualdo. On reading a first draft, a friend noted that an Argentinian writer by the name of Julio Cortázar had already written about the composer in his story ‘Clones’, years before I was born. I already knew of and loved Borges’ writing but had never heard of Cortázar. I was curious and found a version of ‘Clones’ on the internet. After reading it, I immediately bought a collection of his works. Needless to say, my own version remained a first draft; it was a poor shadow of a story written many years before. If I was a character created by Cortázar, you could explain our writing similar stories by saying my identity somehow merged with his for those few hours in which I wrote the draft. But that’s silly. This is real life. Surely I’d know if I was a character in a book.

One thought on “Fantasies of Julio Cortázar”

Comments are closed.