photo provided by U.N.

by Moa Lindunger

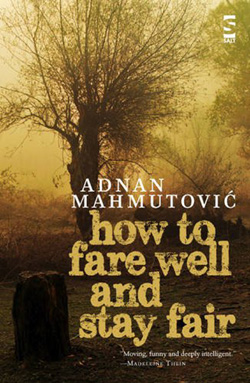

How to Fare Well and Stay Fair by Adnan Mahmutovic is a collection of short stories that question the concepts of home and identity. My experience is that we generally do not expose ourselves to this kind of reflection willingly. This is why we have literature. American novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder allegedly believed that a writer’s major challenge, or even duty, was to pose questions about ‘the vast themes’:

“[There] seems to be some kind of law deep down in human nature whereby the most compelling means of communicating ideas about the nature of what it is to be alive is to enwrap one’s illumination in a story.”

A story, at its best, evokes the readers’ awareness of certain vast themes that have to be contemplated, over and over. It asks the big questions and leaves its readers to find the answers through reflection, turning them into active participants instead of passive recipients.

So, is there a place like home?

In a world characterised by globalisation and increasing migratory movements, this question has, naturally, gained more importance. What we find in this collection is a myriad of stories of home, in which its smells, textures and people are mythologised and romanticised, at times in absurdum – generally known as nostalgia. Home is neither found on a map, nor in a particular building, and it is subjective, deeply emotional and loaded with values. It is, after all, an affair of the heart. We might even call it an ‘incurable condition’, as Mahmutovic does.

In the collection, we follow several characters as they try to settle in northern Europe after leaving war-torn Bosnia. The stories vary in geographical settings, from the Balkans to Scandinavia and back again, but they share a sense of being in between places. The characters hover between home and refuge, myth and reality, exclusion and inclusion, before and after. Even the distinction between autobiography and fiction becomes unclear, as Mahmutovic, himself a refugee, mixes his own voice with those of his characters. The effect is enriching because he shows that home is fictional as much as biographical, that it is really a story. He forces readers and characters alike to reflect on what home means for them.

The first story is a quick account of the author’s life from 1993 to 2012 and follows a young man’s journey from the departure from his home in Bosnia to another home in Sweden. The story consists of several short passages. Each reveals some kind of transfer, beginning with one refugee who is passively ‘moved around the country a lot’. In describing the powerlessness and estrangement the character feels, Mahmutovic proves he is not a writer who is concerned with his readers’ comfort zones. His writing is bold, at times intimidating: ‘Cry when you leave your country, if you absolutely must.’ The first sentence attacks the reader in an uncannily imperative tone of voice, one stripped of all emotion. The second-person narrative gives the feeling that he is repeating instructions from a book titled Being a Refugee for Dummies.

The narrator is as estranged and overwhelmed: ‘Stay away from every one for your mental health’s sake… they will be strangers.’ He writes about the other refugees whom he notices have ‘mutated’, as if ‘infected’ with some weird bug that brings about episodes of nostalgia, aggression or an us-and-them rhetoric. His feeling of estrangement is twofold since he is also a refugee in a country whose inhabitants he generally experiences as cold, with ‘ice blue eyes’.

The read is painful, perhaps even more because I myself belong to this ‘cold people’, and I can’t help feeling unjustly accused – asking myself is this how refugees perceive us? I realise that I have been provoked into using us-and-them rhetoric. This is, I think, Mahmutovic at his best. On the one hand, he is reminding us that the complexities of life cannot be reduced to simple definitions or prejudices. On the other, he is acknowledging that the idea of ‘us-and-them’ is always present, and that we must be aware of its consequences. The reduction of individuals into stereotypes cuts both ways. It is, as one of the characters notices, a game where there are ‘no winners or losers. Or maybe there are only losers’.

The introduction of the narrator’s father is a major turning point: he has agreed to model for his son’s artistic refugee portraits in front of a cabin deep in the cold Swedish woods. But the man refuses to act the role of the ‘miserable refugee’ and keeps smiling despite his son’s mounting frustration.

He won’t stop. He’ll laugh and smirk and guffaw and chortle and do any other take on cheerfulness and the borrowed Hasselblad will capture that, the true, the good, the spiteful.

This is a perfect marriage of opposites: miserable and cheerful. It is not just poetically beautiful, it also reminds us that a person’s identity cannot be captured in a single image or within a single concept. Swede, Bosnian, Serb, Muslim, native or refugee – they are only words, and the properties assigned to each label are fallible.

Likewise, the concept of home is concerned with mythology, rather than reality. This is what Almasa, the main character in the story ‘The Myth of the Smell’, realises whilst discussing home with Björn, a worker at the refugee camp. Björn is provoked by the nostalgic rhetoric of the Bosnians: “They always talk about Bosnian smells, how wonderful it feels to breathe there, while here they are choking. I find it so condescending”. Almasa smiles and asks an old woman, Nijazeta, to tell them about the smells of Bosnian soil and why they are better then the smells of Sweden. Björn objects, diverting the conversation – he has heard that war-torn Bosnia actually stinks, but the discussion is, of course, futile. Inwardly, Almasa acknowledges that the soil of Bosnia has ‘no smell whatsoever’ and that nobody actually believes in the existence of ‘a-place-to-call-home’. But why doesn’t she say any of this to Björn? Because she has realised that, exposed as we all are to the transient nature of life, we need something to hold onto, to belong to, and to believe in. We need a sense of home, which is precisely why we create myths about it and why the idea of home will always be a contested concept.

Acknowledging that home is mythological is not stripping it of its importance. Rather, it facilitates a discussion more fruitful than that of Almasa and Björn. The perspective moves from ‘my home versus your home’ to the notion of what home is itself. Throughout the collection, Mahmutovic sways between these perspectives, in a combination of provocative boldness and tender gentleness, allowing us moments of reflection on these big themes of home and identity.