photo by Josh Nothnagle

Innocence & The Man: Remembering Sam Selvon’s Short Stories

by Cyril Dabydeen

I

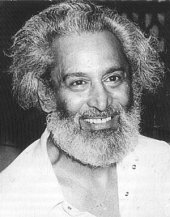

My daughter, age three, looks at the man in the living room, and bursts out screaming. Oh, horror. She’s never seen someone like him before with such a head of hair, the mane almost swept back from his forehead, but hanging down his neck. Grey strands, a bunched knot – and he looks almost gaunt.

Catriona’s innocent eyes blink. I try to comfort her.

Yes, him.

She keeps taking him in, from a safe distance.

I offer more solace. She wipes her tears dry.

Who’s he? I must explain, wanting to say he’s from the Caribbean, a place deep in his bones, embroidered in his memory. Yes, he’s a writer.

I pat my daughter, and she watches the man sitting on the sofa in a strange silence. He talks to me and my wife, Katherine. Who’s he?

The man eats dinner with us, and Catriona is restless. Muttering to herself, her hieroglyph of words, thoughts in disarray.

My wife is meeting him for the first time also. Sam Selvon, the short-story writer par excellence, I’d told her. The folk poet, indeed. And most of us born in the region (Caribbean) know him, have heard of him. From his London days, you see, and places like Clapham Common, Cheswick, Highgate, the Arch, the Gate with liming (hanging out) spots – and more well-known places like Piccadilly Circus, Trafalgar Square. All with that early group of West Indian-born writers in the 50s and 60s, so rooted because of their social consciousness and their uncompromising identity.

This is what I grew up with, knowing about it in strange or just amorphous ways. Everything tied to a colonial past – that Sam Selvon knew best, I figured. A time of political upheaval, ideology, with a longing for independence always hanging in the air. And Selvon would write his stories from a deep sense of his oral beginnings with his Creole cadence. He, with his Indian-Scottish background (some said), and all that he felt of an early village life where he first lived in southern Trinidad or just San Fernando, then in the small city of Port of Spain, before migrating to London, UK.

This is what I grew up with, knowing about it in strange or just amorphous ways. Everything tied to a colonial past – that Sam Selvon knew best, I figured. A time of political upheaval, ideology, with a longing for independence always hanging in the air. And Selvon would write his stories from a deep sense of his oral beginnings with his Creole cadence. He, with his Indian-Scottish background (some said), and all that he felt of an early village life where he first lived in southern Trinidad or just San Fernando, then in the small city of Port of Spain, before migrating to London, UK.

My daughter looks away from me. Selvon manages a smile, trying to disarm or befriend her, as Catriona keeps thinking: who’s this man in her dad and mom’s living room?

I tell her the man is a writer.

“What’s a writer?”

“One who puts thoughts down on paper.”

“What are thoughts?”

“Well…words.”

“Real words?”

“In a book… images.”

Images?

What will I tell her next. “Yes,” I say.

The man eats silently. My wife is taking him in – his unaffected, almost simple way – as we talk about the life of a writer. Then Selvon is about to leave. Catriona hides in a corner, but with a new awareness, maybe. “Is the book-writer really gone?” she asks.

Gone for good?

II

A myriad sense of place and time, and the man really is gone for good – Selvon died in Trinidad in 1994. His photograph is on the back of a book cover, and Catriona studies the image, and maybe she will keep asking: Who’s he? Yes, a short-story writer!

Selvon’s distinctive narrative voice, his characters indelibly drawn with their folkloric appeal, are still forming in me. My own favourite story, a Caribbean classic, is ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough’ (not far unlike V.S. Naipaul’s Miguel Street, characters such as Hat, Bogart and B. Wordsworth). Layered with the Caribbean inflexion and inversion tied to a unique intonation; its rhythms transplanted to London where this particular story is set. Indeed, it is distinctive, most of all because of its depiction of a temper of the times and West Indian migrants’ lives (that first group, so-called) in the 50s and early 60s with their struggle to adapt and survive, and including all their idiosyncrasies. Living in a multi-racial world mingling with others of different hue and creed in cosmopolitan London, coming to grips with British middle class attitudes and values, and rebelling against it in ornery ways. Indeed, Selvon’s unique characters are at it, where language and narrative combine in palaver, as seen in this particular story. And, no doubt reflecting what we find in other Selvon stories too, as anthologized in that seminal volume West Indian Stories, edited by Andrew Salkey. Stories such as ‘Knock on Wood’ (set in London) or ‘Calypsonian’ (set in Trinidad). But, I contend, unlike ‘The Girl in the City’ also set in London, with its more meditative and measured tones conveying what’s innate in the Caribbean spirit undergoing change.

Selvon’s distinctive narrative voice, his characters indelibly drawn with their folkloric appeal, are still forming in me. My own favourite story, a Caribbean classic, is ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough’ (not far unlike V.S. Naipaul’s Miguel Street, characters such as Hat, Bogart and B. Wordsworth). Layered with the Caribbean inflexion and inversion tied to a unique intonation; its rhythms transplanted to London where this particular story is set. Indeed, it is distinctive, most of all because of its depiction of a temper of the times and West Indian migrants’ lives (that first group, so-called) in the 50s and early 60s with their struggle to adapt and survive, and including all their idiosyncrasies. Living in a multi-racial world mingling with others of different hue and creed in cosmopolitan London, coming to grips with British middle class attitudes and values, and rebelling against it in ornery ways. Indeed, Selvon’s unique characters are at it, where language and narrative combine in palaver, as seen in this particular story. And, no doubt reflecting what we find in other Selvon stories too, as anthologized in that seminal volume West Indian Stories, edited by Andrew Salkey. Stories such as ‘Knock on Wood’ (set in London) or ‘Calypsonian’ (set in Trinidad). But, I contend, unlike ‘The Girl in the City’ also set in London, with its more meditative and measured tones conveying what’s innate in the Caribbean spirit undergoing change.

But it is the folk poet’s immanent sense – even if just through the trickster that we encounter in ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough’ – which rings true. Here, the Creole rendition is at its best because everything is couched in Caribbean linguistic nuance.

And almost every evening he would meet the boys and they would

lime by the Arch, or the Gate, and have a cup of coffee (it have place

like stupidness now all over London selling coffee, you notice) and

coast a talk and keep a weather eye open for whatever might appear

on the horizon.

Canadian writer Austin Clarke (Barbados-born) describes Selvon’s rendition as a ‘psychological language’ because of its liberating power – it frees the West Indian mind from colonial hegemony stemming from what’s viewed, conventionally, as standard Queen’s English.

Sam Selvon kept his distinctive Trinidadian or West Indian voice intact in his literary self and manner as he depicted what was authentic. His stories are his “ballad” (he calls it), reflecting what’s quintessentially oral and a literary ground-breaker, as he captures the foibles of West Indian immigrant life at home and abroad. In re-reading his stories it’s as if one has never left home – everything is captured in each brush-stroke of the pen, seen in ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough’. Here, we find the whimsical, or just strange behaviour or interaction between Brackley with his English girlfriend, Beatrice, as they wait for Aunty to cough in the middle of the night – where the real drama begins to take place: ‘Sleep killing Brackley but the doorway small and he bend up there like a piece of wire, catching cramp and unable to shift position. In fact, between five and halfpast Brackley think he hear Aunty cough and he make to get up and couldn’t move, all the joints frozen in the damp and cold.’

In the story ‘Calypsonian’, the character Razor Blade – an erstwhile calypsonian and now a layabout – is forced to steal in order to survive. But he becomes a character of humour, for everything is couched in pathos and we feel sympathy for him, as much as we identify with Bradley – or, to some extent, with the superstitious Jupsingh in ‘Knock on Wood’, also set in London in the 50s.

Indeed, it is this shifting back and forth, temporally and spatially, that one finds in most immigrant writers’ works as they straddle two or more worlds. Imbedded in the structure of their stories is the linguistic embroidery or tapestry, always authentically West Indian at best. Selvon’s folk rendition is akin to a blues singer with words, a jazz player with a trumpet or horn in New Orleans. He turns Standard English on its head with tone or cadence, identifying what’s now commonly called the new literature or post-colonial literature. I first heard Selvon read ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough’ on the BBC radio programme Caribbean Voices, produced by the pioneer Henry Swansea, decades ago. I clearly remember what was beamed to us when I lived in then British Guiana. Selvon’s voice came over with its particular but familiar resonance, essentially a village voice without pretence of grammatical correctness or an expected English-style, as seen in the regular Jane Austen-type fare.

Selvon’s story-telling became immediate folklore with long-lasting echoes, due to his natural voice in narration and dialogue, as everything reaches the denouement in ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough.’ I laughed then because of the self-realization of the pathos and poignancy, always seen in the sense of comedy in our lives, and simultaneously being what keeps making us aware of our own life’s situation, through self-criticism (as Andrew Salkey notes). But Selvon’s art reflects more than the gritty life in Trinidad or what new immigrants experience in the London of the 50s and 60s, as he keeps being the folk poet and balladeer. Indeed, I keep waiting to hear more echoes in ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough’ as Brackley tries to ‘entertain’ his white girlfriend, Beatrice, with sheer guile or mischievousness – the trickster at work – now to awaken Beatrice’s dour aunty from her fitful sleep in the house. Beatrice, you see, forgot the door key, and she and Brackley are suffering in the cold outside in the early London morning air. While Beatrice reclines on Brackley’s arm and appears to fall asleep, Brackley’s mind is busy looking for a solution: a way of ‘liberation’. Finally, he starts ‘pelting’ a heavy brick at the house in order to rouse the aunty – to Beatrice’s amazement and horror. In the story’s resolution the aunty wakes up in time to see Brackley taking off as ‘if he is on the Ascot racecourse’ – leaving Beatrice alone, totally dismayed.

Not unexpectedly, Brackley’s antics are repeated, as word gets around, in his fellow West Indians’ taunt: “Brackley! You still waiting for Aunty to cough?” This, we imagine, will remain hilarious and no doubt haunt Brackley for the rest of his life with ribald laughter following.

“You see,” Selvon once told me, “I had to go to England to understand Trinidad. I couldn’t do that while remaining there.” It was a revelation, of colonialism and its grip on the psyche. After leaving London, he immigrated to Calgary – to be closer to his native Trinidad, he told me – and here he lived until he passed away.

In this context, I will mention the last story Selvon may have written, ‘Ralphie at the Races,’ which shows his almost “new” style with more formal syntax, but not without his inimitable flair and cadence of his deep-seated island-rhythm sensibility. I included this story in my recently edited Beyond Sangre Grande: Caribbean Writing Today (TSAR Publications, Toronto), maybe to reflect Selvon’s Canadianness, if such, with his usual wit, if not comedy, of what keeps adding to the folklore he has cultivated and established.

In this context, I will mention the last story Selvon may have written, ‘Ralphie at the Races,’ which shows his almost “new” style with more formal syntax, but not without his inimitable flair and cadence of his deep-seated island-rhythm sensibility. I included this story in my recently edited Beyond Sangre Grande: Caribbean Writing Today (TSAR Publications, Toronto), maybe to reflect Selvon’s Canadianness, if such, with his usual wit, if not comedy, of what keeps adding to the folklore he has cultivated and established.

Selvon will continue to attract readers, old and new, though I contend that Caribbean-born peoples will always give him a special place of recognition (more than for the short story form). Many would speak of his giving legitimacy to ‘our voice’. And, each time I re-read ‘Waiting for Aunty to Cough,’ or others like ‘Knock on Wood’, ‘Calypsonian’, or ‘My Girl and the City’ – or his novels Lonely Londoners and Moses Ascending – it will be a time when everything comes afresh, a time of where one has come from, and perhaps of where one is going (to allude to the legendary scholar, C.L.R. James). It is only the ubiquitous imagination being at work, but with the sense of journeying and realizing people for being who they truly are. This will always come to me in unsuspecting ways because of Selvon’s special appeal as he bridges the divide of the metropolitan and the rural, the English sensibility and the West Indian temperament.

“Let the work speak for itself,” Selvon often said, with his intuitive sense of where creativity comes from, as he keeps sending me back ‘home’, or to the place of origins, nowhere else. And I will keep “cogitating” – one of his favourite words, Victorian-sounding – as I also will peel back layers of consciousness, but not without my awareness of Selvon’s intricate folklore. Like the blues singer in America – the same I would want to tell my daughter about, if no other, all in time to come.

~

Cyril Dabydeen – a former Poet Laureate of Ottawa – has published in over 60 literary magazines, including the Critical Quarterly, and in the Heinemann, Oxford, and Penguin Books of Caribbean Verse. He adjudicated for Canada’s Governor General Award for Poetry and for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature (U of Oklahoma). He has written 20 books–including seven collections of short stories. His novel, Drums of My Flesh, had been nominated for the IMPAC/Dublin Literary Prize, and won the top Guyana Prize for Fiction, 2007. He is with the Department of English, UOttawa, Canada.

Cyril Dabydeen – a former Poet Laureate of Ottawa – has published in over 60 literary magazines, including the Critical Quarterly, and in the Heinemann, Oxford, and Penguin Books of Caribbean Verse. He adjudicated for Canada’s Governor General Award for Poetry and for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature (U of Oklahoma). He has written 20 books–including seven collections of short stories. His novel, Drums of My Flesh, had been nominated for the IMPAC/Dublin Literary Prize, and won the top Guyana Prize for Fiction, 2007. He is with the Department of English, UOttawa, Canada.

Lovely to see that you enjoyed this post, Dora. Cyril has given us such a wonderful insight into Sam Selvon here and it’s great to hear that you feel inspired!

I’ve been in an avid reader of Thresholds and I read it religiously for its wonderful articles and pieces which give me insight into the writer’s life and their short stories. I am getting quite an education and I thank you. I loved this article and I will definitely add Sam ’s stories to my collection .Being an immigrant myself and struggling with my own writing voice, I love being inspired by other writers who have accomplished it.

Cyril, many thanks for this rich & wonderful piece. It’s an honour to have you contributing to THRESHOLDS. with best wishes, Alison