photo crop © Stefan Lins, 2009

*

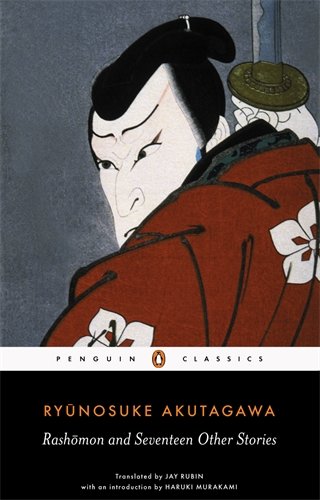

In this longlisted essay from the 2016 THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition, Scott Wilson discovers the best way to kill a man in Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s ‘In a Bamboo Grove’.

~

How to Kill a Man

by Scott Wilson

How do you kill a man, and get away with it? It is a problem that often vexes writers, members of crime syndicates, and others employed in morally grey professions. Murder is the ultimate crime and, as readers, we are routinely transfixed by stories that feature clever killers. These killers often exhibit a style of creative and lateral thinking that is strangely mesmerising to read or watch.

Murder mysteries are commonplace and popular. No matter how many heads well-meaning critics sever in the crusade against crowd-pleasing chicken feed, the Hydra that is Hollywood’s yearly film output routinely boasts blood-spattered thrillers. In 1827, opium-taking essayist Thomas de Quincey wrote of murder ‘as one of the fine arts’, and it is Sherlock Holmes who holds the title of most adapted literary character. Just as Einstein admitted he stood on the shoulders of giants, the stature of Holmes was largely founded upon the ingenuity with which the detective’s murderous antagonists stacked the corpses beneath him. It is clear: we are transfixed by the problem of how best to kill each other and get away with it.

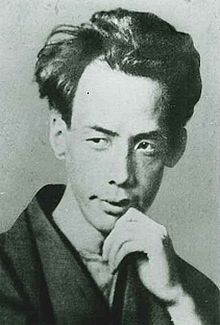

The solution to this problem is answered most elegantly by the master of Japanese modernism Ryunosuke Akutagawa. To kill a man and get away with it, you must do it in a bamboo grove.

In most editions I have read, ‘In a Bamboo Grove’ rarely spans more than ten pages. An unnamed samurai has been discovered dead at the centre of a thick bamboo grove, surrounded by obvious signs of struggle. The narrative consists of seven ‘testimonies’, each given to a magistrate in a form that is structurally similar to contemporary monologues. Pauses and facial expressions are noted much like stage directions within the statements themselves:

I don’t know whose sin is greater – yours or mine. (A sarcastic smile). Of course, if you can take the woman without killing the man, all the better.

Although the magistrate’s questions are answered he never speaks. In turn, he takes the statements of a woodcutter, a travelling priest, a policeman, an old woman, the legendary criminal Tajomaru, and a priestess. To each he asks their account of a murder and crime scene, with the final ‘testimony’ given by a medium channelling the dead man’s spirit.

Although the magistrate’s questions are answered he never speaks. In turn, he takes the statements of a woodcutter, a travelling priest, a policeman, an old woman, the legendary criminal Tajomaru, and a priestess. To each he asks their account of a murder and crime scene, with the final ‘testimony’ given by a medium channelling the dead man’s spirit.

Chillingly, each ‘fact’ given by one of the seven refutes a ‘fact’ given by one of the others. Reading ‘In a Bamboo Grove’ becomes an interactive exercise in the problem of investigation. As reader, you are the magistrate and, as with all psychological thrillers, not everything you’ve been told is the truth. This parade of ‘fact-refutes-fact’ happens at such a mathematically precise level it is astonishing – each character’s professed fact refutes the facts another character has given, without fail. Akutagawa’s short story demonstrates such dedication to detail it makes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s unique approach to Holmes’ theories look like the work of a hobbyist.

This is where praise for Akutagawa’s narrative is routinely founded. ‘In a Bamboo Grove’ is an academic touchstone for creative writing classes: this is what a great short story looks like. The writing of a structural masterpiece depends upon mastery of detail. Well-maintained mechanisms of formatting, pre-planning, and foresight, are as much a part of a writer’s arsenal as the effective deployment of imagery, character and dialogue. For many, this short story also serves as a gateway to the cornucopia of complex emotional studies that is one of the expedient and everlasting features of Japanese modernism.

It is a shame, then, that admiration for ‘In a Bamboo Grove’ rarely strays from its merits as a structural masterpiece. Written in 1921, Akutagawa’s plot is a swan-song for a Japan in metamorphosis. Dynastic systems of honour, which had provided Japan with a sophisticated and absolute moral compass, were now unable to provide solutions to modern problems. Having emerged prosperous from the First World War, Japan in the early 1920s was a country transforming itself through mechanised business and liberal policies. Not only did traditional samurai values seem unfashionable, they often stood in opposition to new opportunities that were radically improving the quality of life across Japan.

Honour codes had provided a regimented system that dictated how to act in a crisis. Honour enforced the stations of those in established professions (such as magistrates and priests), whilst demonising those who resisted these values (such as Tajomaru the criminal, who delivers the fifth testimony in the story). Yet Akutagawa positions this system of respect and self-evaluation as the very mechanism which destroys the magistrate’s investigation: every character interviewed lies to him, because their own honour codes demand they do so.

Tajomaru, the thief, confesses outright to killing the samurai: ‘Sure, I killed the man […] I’m not going to hide anything. I’m no coward.’

Tajomaru, the thief, confesses outright to killing the samurai: ‘Sure, I killed the man […] I’m not going to hide anything. I’m no coward.’

Surely, this closes the case – a notorious criminal is guilty of notorious crimes. Yet later interviews indicate that although the samurai and the criminal duelled, it was not to the death – Tajomaru only captured him. So why does Tajomaru insist upon his own guilt, when admitting so guarantees execution? Tajomaru has been captured and basks in the reputation of a legendary outlaw. To admit to the ultimate crime is to guarantee the legend of his badness; to argue his innocence would be to admit that someone else in that grove had been even more wicked than he had been.

The next interview, with a ‘penitent priestess’ reveals that she is the wife of the murdered man in hiding. She cannot return to her previous life due to the shame she bears after being assaulted by Tajomaru after her husband was overpowered. Her story directly contradicts the account given by Tajomaru. She admits to the murder of her husband, and despairs at her lack of courage in failing to kill herself afterwards. Whereas Tajomaru is shameless, the priestess is ridden with shame:

Now that I have killed my husband, now that I have been violated by a bandit – what am I to do? Tell me, what am I to… (Sudden violent sobbing).

Further complicating the magistrate’s attempt to consolidate the facts, the testimony of the dead man, as told through a medium, alleges the samurai killed himself after losing his duel. Throughout his vitriolic statement, he demonises his wife whilst exonerating Tajomaru:

I am ready to forgive the bandit his crimes […] lying there was the dagger that my wife had dropped. I picked it up and shoved it into my chest. Some kind of bloody mass rose to my mouth, but I felt no pain at all.

Here we see the honourable course of action for the fallen samurai. Self-execution, as his honour code dictates. Anything less and he would be forever ashamed within the culture that fostered him. His position is that the ultimate crime was self-inflicted, yet for this to be true, all other accounts must be false.

Through conforming to a system of honour that no longer serves the rapidly reforming values of contemporary Japan, Akutagawa’s characters are ashamed, executed, murdered, or perplexed, as must be the case for the poor magistrate presented with an unsolvable case. Positions of authority and establishment are undermined by the very values they allege to uphold.

This is Akutagawa’s masterstroke – how do you kill a man, and get away with it? The answer is simple: you get someone else to admit to it. No one is prepared to say what really happened in the bamboo grove. As such, the truth is annihilated by the collusion of ‘honest’ and honourable voices, rather than preserved by them. It is the perfect murder when no one can agree how it happened or what was seen, and a beautifully constructed allegory of a nation in departure from the ethics espoused by dynastic forefathers.

The final image is of the fatally wounded samurai, dying beneath ‘the lonely glow of the sun’. He dies in ‘perfect silence’ on ‘the hidden side of [a] mountain […] among high branches of cedar and bamboo’. Here, traditional Japan lies dying and unable to effectively articulate precisely what killed it. Akutagawa leaves the reader with an unsettling image of an anonymous killer, and the impossibility of comprehensive truth:

I tried to see who it was, but the darkness had closed in all around me […] someone gently pulled the dagger from my chest with an invisible hand. Again a rush of blood filled my mouth, but then I sank once and for all into the darkness between lives.

~

Scott Wilson is a budding playwright and novelist. He has been shortlisted for the 2015 Anthony Burgess / Observer Prize for Arts Journalism, awarded in February 2016, and the Bath Flash Fiction Award, and will feature in an anthology published in December 2016. He is currently working on a series of monologues and a retelling of Oliver Twist.

Scott Wilson is a budding playwright and novelist. He has been shortlisted for the 2015 Anthony Burgess / Observer Prize for Arts Journalism, awarded in February 2016, and the Bath Flash Fiction Award, and will feature in an anthology published in December 2016. He is currently working on a series of monologues and a retelling of Oliver Twist.