photo © Kat N.L.M, 2013

Never Just One Thing, Or: How to Create

a Sense of Movement in a Story

by Shaun Levin

For a long time my thing was description. I liked doing it and I liked teaching it: the struggle to find precise words for objects, feelings, landscapes and the things people do with their bodies. I liked the stillness of description, its meditative nature. I still like description but not as much as I like movement.

Having spent the last six months creating The Writing Notebooks – a guide and workspace for writers – I’ve had to be clear about what my ‘thing’ is. Now my thing is movement. Recently, on the phone to my friend, Steve, we agreed that even if a character (or you) is sitting in a room staring at a ceiling, a wall, or out a window – even if we’re in the dark – movement must happen. A story without movement is kaput.

Having spent the last six months creating The Writing Notebooks – a guide and workspace for writers – I’ve had to be clear about what my ‘thing’ is. Now my thing is movement. Recently, on the phone to my friend, Steve, we agreed that even if a character (or you) is sitting in a room staring at a ceiling, a wall, or out a window – even if we’re in the dark – movement must happen. A story without movement is kaput.

“And by a story,” Steve said (from his garden), “you mean life in general.”

Kafka, we said, manages, in a 181-word story (160 in German), ‘Passers-by’, to include an account of: 1) what is happening, 2) questions regarding what might actually be happening, and 3) a mention of what had been happening before all that is happening started. Present, future, past. Suspense, landscape, thoughts, drama. The lot. All in a story about a man (Kafka, you, us) out one night for a walk in the city.

In ‘Passers-by’, movement happens seamlessly.

When you go walking by night up a street and a man, visible a long way off […] comes running toward you, well, you don’t catch hold of him […] not even if someone chases yelling at his heels.

[…] besides, these two have maybe started that chase to amuse themselves, or perhaps they are both chasing a third, perhaps the first is an innocent man and the second wants to murder him and you would become an accessory, perhaps they don’t know anything about each other and are merely running separately home to bed, perhaps they are night birds, perhaps the first man is armed […]

~ You can read ‘Passers-by’ in full here, and find an animated version here.

Watch the perspective shift 180 degrees, the gaze following the men as they run down the street. First they come into view, then they disappear. Kafka’s story happens in a moment, and in that moment is constant movement, because, as Steve said, that’s life in general. You sit on a sofa: a Tartan throw on your lap; the sky clearing outside your window; memories of the tea you’ve just drunk (that was a good biscuit!); thoughts of what is about to happen, or what you’d like to happen; traffic noises from outside, children playing; your phone next to you waiting to be picked up to check if your lover has emailed. Have you missed their call? All happening at the same time. The challenge is to tell that story succinctly and accurately.

Watch the perspective shift 180 degrees, the gaze following the men as they run down the street. First they come into view, then they disappear. Kafka’s story happens in a moment, and in that moment is constant movement, because, as Steve said, that’s life in general. You sit on a sofa: a Tartan throw on your lap; the sky clearing outside your window; memories of the tea you’ve just drunk (that was a good biscuit!); thoughts of what is about to happen, or what you’d like to happen; traffic noises from outside, children playing; your phone next to you waiting to be picked up to check if your lover has emailed. Have you missed their call? All happening at the same time. The challenge is to tell that story succinctly and accurately.

Lydia Davis also provides a demonstration of how it’s done. In an even shorter piece, ‘Dog and Me’ – just seventy-seven words – Davis manages to leap from one strange image to the next: an ant with fists; a human dog; a human on a hot day with tongue hanging out, but not; a person barking at a dog, “No! No!” In this story, she (narrator, character) dwells on the question of perception, on who we are in relation to each other, what makes us different and, in the end, how we might be the same.

By its nature, writing is movement, even if we’re doing it on a keyboard, writing is born out of movement. No matter how much of the story you work out in your head, the one that materialises when the pen gets going will be quite different. Movement creates its own story, and the mind moves differently when following a pen. The challenge is to stay true to the mind’s agenda, to follow the simultaneity of events: actions, questions, sensual experiences, memory, intrusions of the world. All happening at once.

Movement opens up a story to accident and surprise.

What I’m trying to say is that the mind isn’t static, and writing – all art? – is a record of the mind and its interpretation of experience. Movement happens in time, in space, internally and externally, past, present, future. The movement of a character on a beach, lying in a hospital bed, remembering the waves, a purple starfish on wet sand. The movement of making a cup of tea while you’re on the phone to a friend as he prepares his garden for the winter.

“You’re doing too much,” Steve says.

“You’re doing too much,” Steve says.

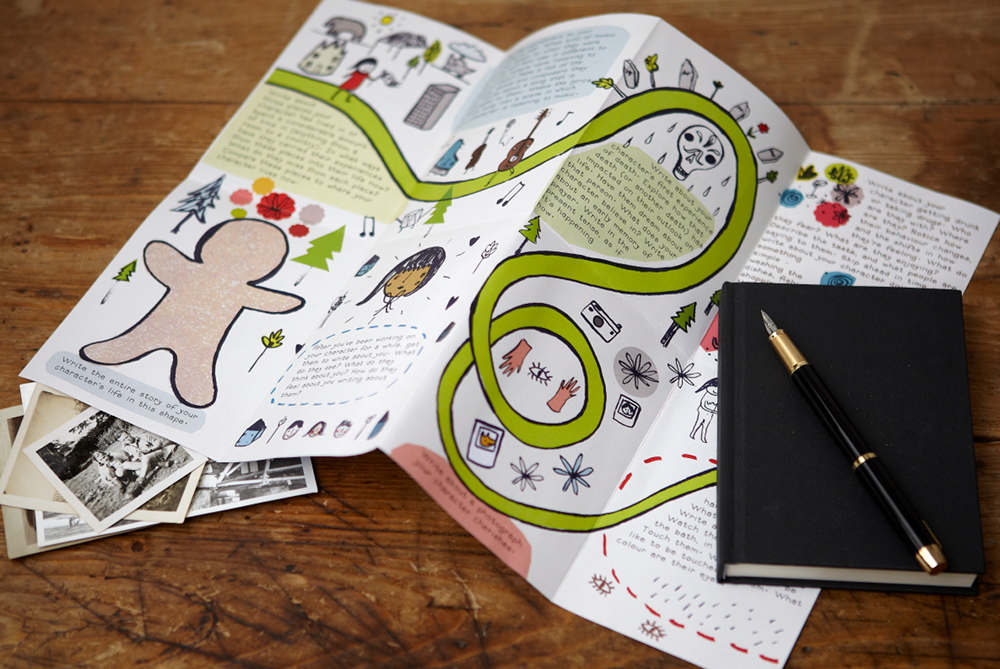

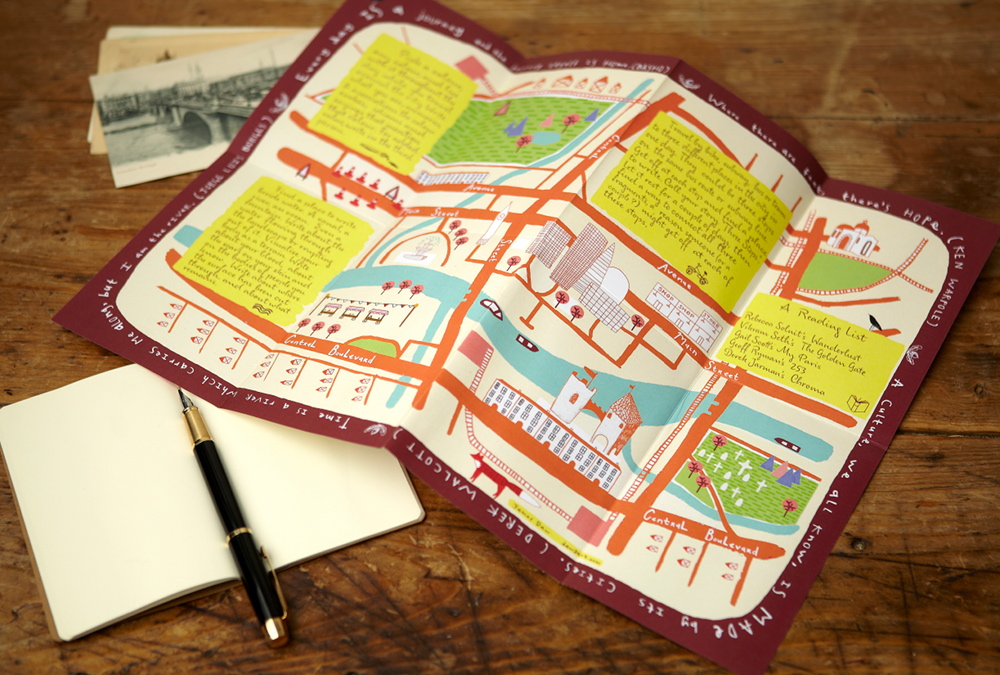

I set up a little journal about eighteen months ago, a fold-out single A3 page called The A3 Review. It happened organically, born out of the Writing Maps I’ve been devising for the past three years – maps with creative writing prompts on them, the kind of prompts one offers participants in a workshop. Often, out of these timed exercises, the most moving and vital writing takes shape. I think the mind lets go when it’s contained, when it stops worrying about performance and audience and getting it right; when it thinks it’s just doing a little writing exercise. That’s the kind of writing I’d like the Maps to inspire, the kind of writing I’d like The A3 Review to attract.

Writing that lets go.

It’s like sprinting. Quick bursts of writing limber you up. But you can also check for movement in a story. A strange contradiction. On the one hand, letting go; on the other – a movement checklist.

1. Check your sentences. Do you have a mixture of short and long sentences. It’s that basic. Too many sentences of the same length create monotony, a droning voice.

2. Check your tenses. In other words, flashbacks and flashforwards while telling the story of what’s happening now. A flashback can be one or two lines. Memory is the past. Desire is the future. Dreaming can be everything mixed up.

3. Check your perspectives. Bob looks at Barbara, but also imagines what Barbara sees when she looks at him. We’re not changing POV; we’re getting another perspective on things, even if that perspective is only Bob’s imagination.

4. Check your questions. Include the character’s not-knowing; their puzzles. Not-knowing creates a story within a story. ‘…perhaps the first is an innocent man and the second wants to murder him…’

5. Check your characters. Even if they’re not there, think about them, have your character think about them.

More often than not, these points will all be in the story if we just follow the mind’s meanderings. Notice if too much is happening in the present. Add a flashback, a character remembering something. Does most of your story concern a single character? Find ways to bring others into the story, whether through recollection or desire, in person or on the phone. Check if you have scenes happening at different times of day, different environments, indoors and out.

6. Check your paragraphs. Even in Kafka’s short short story the three paragraphs are different. Pages, or even one page, with similar blocks of text, create a droning effect.

7. Check your location. What other places can you add to your story? Notice how the location shifts, pretty much from one comma to the next in Jamaica Kincaid’s ‘Girl’. (Watch Kincaid read ‘Girl’, here.)

8. Check your ending. Has there been movement, both physical and psychological, since the story began a couple of hundred words ago?

At some point you’ll forget all this. The checking, the making sure, and you’ll move back and forth in time, from long sentence to short, from stillness to sprint, from inner world to outer, up in the air to underground, and it will be effortless because it will be natural. It is natural. You only have to sit in a hotel room in Berlin in the evening to know this, while the birds chirp wildly in the trees along Boxhagener Strasse, a child cries in the courtyard, Steve’s voice lingers in your ear, all of this happening simultaneously as you work your way through an essay you’ve been meaning to finish for months and then finally arrive at the end.

~

Shaun Levin is the author of Seven Sweet Things, Snapshots of the Boy, and a collection of short stories, A Year of Two Summers. His most recent publication is the first three notebooks in The Writing Notebooks series. He creates Writing Maps. See more at shaunlevin.com and writingmaps.com.

~

Writing Maps are illustrated posters that fold down to postcard size and are devised to keep writers writing. Creative writing prompts and story ideas to inspire explorations of places, characters and points of view in fiction, memoir and creative non-fiction.